Welcome to 2021. Space aliens are roaming overhead. Russian spies are zapping American diplomats with microwave weapons. And the commies are covering up a viral bioweapon.

This is the year shaky science and government intelligence reports have collided, turning the news into the stuff of a bad thriller — three bad thrillers, actually. Declassified US Navy images of blurs on screens have triggered a UFO frenzy, boosted by breathless reporting from 60 Minutes and the New York Times. Intelligence agencies suspect that Russian agents have fired physics-defying microwave weapons at federal employees in Havana, Beijing, and Washington, DC, according to CNN and Politico. And legitimate scientific questions about whether the coronavirus could have escaped from a lab have metastasized into theories about Chinese bioweapons.

In the absence of any real evidence, US intelligence reports — typically shrouded in secrecy — are fueling a flurry of speculation over today’s biggest scientific mysteries. Yet history has shown that intelligence agencies are not equipped to quickly solve scientific problems, and their findings look more likely to spark fear and confusion rather than crack any cases.

Although they all boast technical expertise, intelligence agencies, at their heart, are not really focused on solving scientific mysteries, said Loch Johnson, a political scientist at the University of Georgia and senior editor of the academic journal Intelligence and National Security. They are good at analyzing political situations and spying, he said, “but when it comes to scientific matters, we really fall off.”

On Friday, a congressionally ordered intelligence report on 144 potential UFO incidents was released, finding...well, not much. “The limited amount of high-quality reporting on unidentified aerial phenomena (UAP) hampers our ability to draw firm conclusions,” it concluded. And more intelligence reports are on their way. The US government is conducting intelligence reviews on the origins of the pandemic in China, due on Aug. 24. And an ongoing National Security Council intelligence review is looking into whether cases of the mysterious “Havana syndrome” neurological injuries are happening worldwide.

Just don't be surprised if these efforts, like the UFO report, don’t turn up any real answers, experts told BuzzFeed News. “There is just so much noise around all three of these issues right now; the signal-to-noise ratio, as we say, is terrible,” said former Los Alamos National Laboratory chemist Cheryl Rofer. “I don't see how anyone makes any sense of it.”

Bad science and bad intelligence.

Historically, when politics, intelligence, journalism, and science collide, bad things happen. Incidents of federal intelligence agencies botching scientific mysteries go at least as far back as the Cold War and have continued since. In 2006, the FBI and the Energy Department led a nuclear espionage investigation into Los Alamos National Lab scientist Wen Ho Lee that blew up so badly that the government — and five news outlets — paid him a $1.6 million settlement. Another botched forensic investigation caught headlines for linking virologist Steven Hatfill to the 2002 anthrax attacks, leading to a $4.6 million settlement. The same year, the CIA’s “slam dunk” findings of “weapons of mass destruction” in Iraq became one of the most notorious intelligence screwups in history.

Now some of the same agencies behind these investigations are being asked to dig into the possible national security threats posed by aliens, Russian microwave weapons, and the origin of the novel coronavirus.

Intelligence agencies face big hurdles to solving scientific mysteries like these. The first is that the science is at best absent or half-baked, said Rofer. In reality, scientific investigations of any complexity usually take years. In the meantime, intelligence reports can explore multiple theories, with the most entertaining ones often getting the most attention. “Everyone loves a good death ray,” she said, referring to a theory for why diplomats across the world appear to be suffering from neurological injuries. “It's just not as much fun to hear there's no evidence for a microwave weapon.”

A second is that intelligence reports are never as conclusive as scientific experiments, and almost always have an element of human judgment baked into them. “I think most Americans tend to believe that ‘intelligence report’ actually means something authoritative and vetted, like a peer-reviewed scientific journal article,” said Alex Wellerstein, a science historian at the Stevens Institute of Technology. “Anyone who has worked with intelligence reports knows that this is an entirely wrong way to think about them.”

“Everyone loves a good death ray.”

Intelligence reports are typically carefully hedged by the level of confidence that analysts have in their sources. This crucial context is often absent from news stories leaking details of reports. “One thing I don't think is widely appreciated is that the classification of something often has less to do with the actual information than with how we got it,” said Philipp Bleek, a nonproliferation and terrorism expert from the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, who served on a Defense Department task force on Syrian chemical weapons during the Obama administration.

“The information might actually be quite banal, and even available in a newspaper,” Bleek said. “But the fact that we got it by tapping the personal cellphone of a key official, or maybe because that official is an informant for us, that's what makes the information so sensitive.”

The final hurdle, and the biggest one, comes from the motivations of people leaking parts of intelligence reports, or making claims about them.

“The people who are getting this out have their own motivations,” said Rofer. “Not all those motivations are in the public interest, and not all of them are even obvious.”

UFOs could be aliens...or glitching sensors.

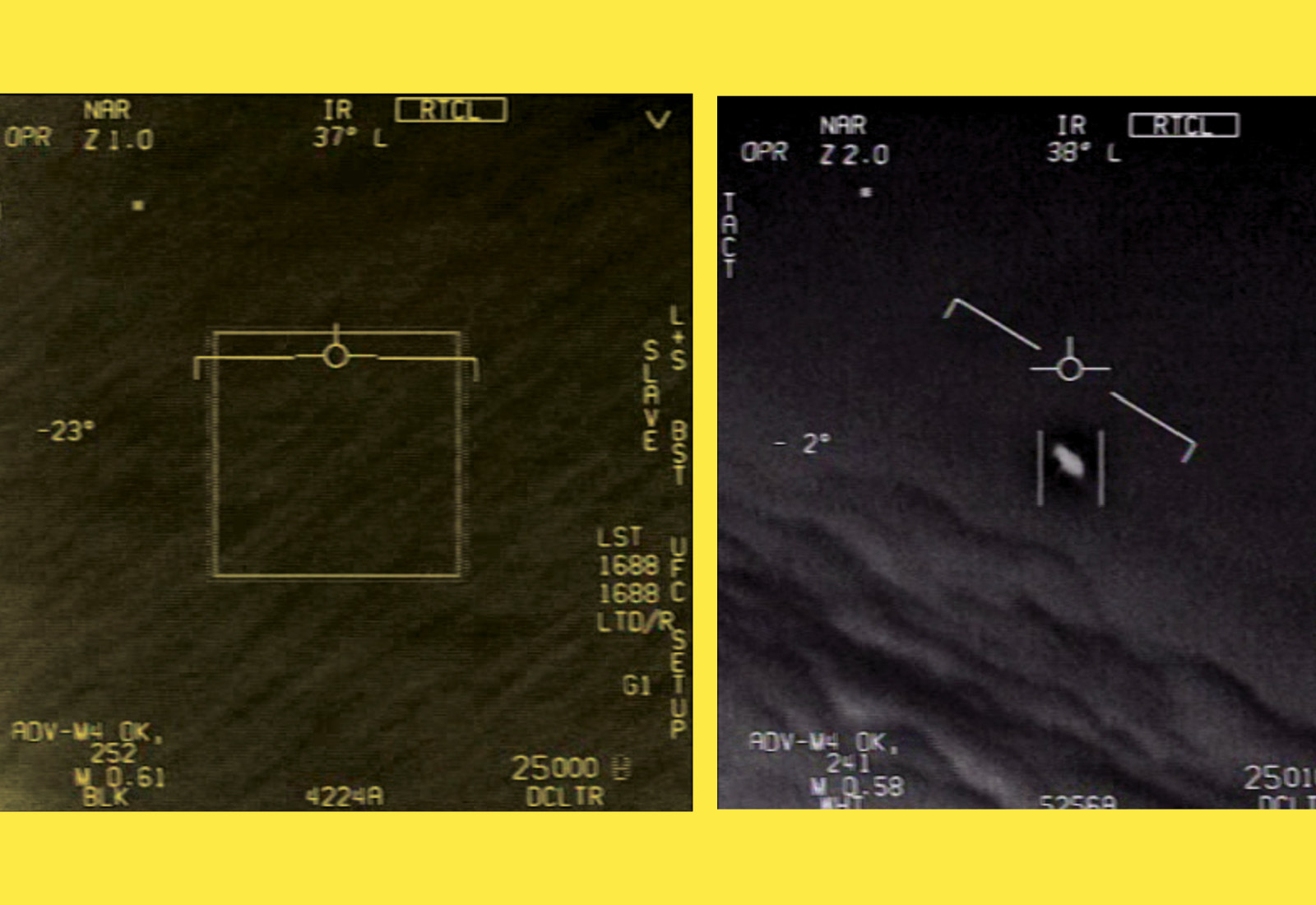

UFOs are the original pop science mystery, going back to 1947’s “flying saucer” fever. The latest space alien speculation cycle kicked off in 2017 after three leaked Navy videos showed various blurs moving across jet pilots’ infrared tracking screens. And it got the attention of Congress after a report that same year in the New York Times revealed that the Defense Department had run a program looking into UFO sightings.

The excitement has continued since. A Senate committee report from June 2020 revealed that the Defense Department had appointed an Unidentified Aerial Phenomena (UAP) Task Force to investigate “incursions of unauthorized aircraft.” In March, Sen. Marco Rubio of Florida talked up UAPs as a possible military threat on 60 Minutes. And former president Barack Obama added to the mystery on a late-night talk show in May, saying, “There is footage and records of objects in the skies that we don’t know exactly what they are.”

“I will say that the UFO community is abuzz. I've never seen anything like it since I’ve been working in this area of history,” said Greg Eghigian, a science historian at the Pennsylvania State University. Mainstream media coverage, he added, was leading many UFO enthusiasts to feel “vindicated” that the field was finally being taken seriously.

But the current UFO moment has all the hallmarks of past ones: strange bedfellows, lots of excitement, and little in the way of answers. The New York Times report on the US intelligence program was spurred in part by a former Pentagon official, Luis Elizondo, who until last year was part of a Las Vegas entertainment company founded by Blink-182’s former guitarist. Elizondo, whose role at the Department of Defense has since been disputed, was backed by an enthusiastic, influential politician, former Senate majority leader Harry Reid of Nevada.

And as usual with UFOs, alternate explanations that the images were more likely caused by mirages affecting radar, infrared, and visual observations — well understood for decades — are rarely mentioned in news reports that describe the possibility of space aliens.

“In terms of evidence, nothing has changed since the 1947 flying saucers, but now it is in the form of [infrared] videos taken by advanced aircraft that look impressive,” Vicente-Juan Ballester Olmos, who writes the UFO FotoCat Blog, a long-running catalog of UFO images worldwide, told BuzzFeed News in an email.

“In terms of evidence, nothing has changed since the 1947 flying saucers."

The data in today’s sightings — typically blurry figures recorded by fighter jet cameras — is intrinsically ambiguous because it was collected for a purpose other than a scientific search for alien life. And it is similarly obscured by military secrecy, so we don't know much about the instruments that captured the images or their limitations. Of the 144 sightings mentioned in the new UFO report, 18 had unusual flight patterns that the Office of the Director of National Intelligence said deserved further investigation, and one was identified as a deflating weather balloon. Rubio called the report an “important first step” in a statement on Friday, but many UFO fans were disappointed.

Nevertheless, UFO enthusiasts have plenty of motivations to feed the hype, from peddling books to scoring research money to boosting military budgets.

“What has kept this alive is mystery and melodrama,” Eghigian said.

“Havana syndrome” could be caused by death rays...or mass psychology.

The second of this year’s hot mysteries started in Havana in December 2016, with one US diplomat coming down with dizziness, headaches, and other neurological symptoms, according to a CDC analysis first reported by BuzzFeed News. One of their colleagues reported similar symptoms in February 2017, reportedly sparking a “rumor mill” at the embassy.

Staffers were then asked to report similar symptoms, with 95 people eventually treated or evaluated in the first outbreak. Only 15 of those people appear to have actually had the syndrome, marked by an initial onset of head pressure and neurological symptoms accompanied by buzzing sounds and later followed by balance and concentration problems that can last for weeks, months, or years. In August 2017, former secretary of state Rex Tillerson declared the syndrome a “health attack” on American diplomats.

National security reports have since expanded the number of government officials who may have been victims of such attacks. On May 12 this year, a New York Times report based on leaks from multiple intelligence agencies said that more than 130 “spies, diplomats, soldiers and other US personnel” in China, Cuba, and even Washington, DC, were reportedly experiencing similar symptoms, triggering an ongoing intelligence review.

The problem is there’s no good explanation for the syndrome. Although it was initially reported as a brain injury caused by “sonic attacks,” explanations have since ranged from crickets to a tropical illness to pesticides to mass psychology. A National Academies of Sciences report in December 2020 said that pulsed microwave weapons that could cause neurological injuries are the “most plausible” explanation for the illness. But experts in microwave technology have fiercely criticized the theory.

Adding to the confusion, it may not even be one syndrome, as the reported symptoms vary wildly. The “brain injuries” most often reported may not even be real.

And data on the injuries is patchy. A BuzzFeed News investigation in 2019 found that the two medical teams treating injured diplomats weren’t sharing data with each other, resulting in studies with different conclusions. The State Department is now referring these cases to the National Institutes of Health as part of a long-term study, according to Politico.

Further complicating things, security classifications and medical privacy laws add to the secrecy. The 2018 CDC report was released with several pages completely blacked out. Some of the injured individuals have reportedly worked for the CIA. And much of the research on microwave weapons is done in military settings, stifling any discussion of what is actually technologically possible.

Lastly, the motives behind whoever is leaking information about intelligence investigations into the syndrome are all over the place. Military research money is already going into microwave weapons, making the advent of a new syndrome a potential cash spigot for the labs. It was convenient for the Trump administration — already hostile to Cuba — to blame its government. The most prominent lawmaker’s voice on the issue today is Rubio, whose Florida electorate includes many Cuban expatriates hostile to the country’s government. Trump and Biden administration officials, according to the New Yorker, have since proposed that Russian intelligence agents made the targeted attacks, a convenient explanation given that the country is already implicated in the poisoning of dissidents outside its borders.

“What does that mean if indeed we have Russians running around, zapping people in Washington and Beijing?” Rofer asked. She noted that using such a weapon would be wildly conspicuous: A microwave weapon that could deliver the theoretical “directed energy” effects blamed for the syndrome would need to be the size of a truck. “It’s kind of absurd.”

A “lab leak” could be a Chinese bioweapon...an accidental lab escape...or neither.

On June 14, comedian Jon Stewart went all in on the “lab leak” theory on The Late Show With Stephen Colbert to proclaim how SARS-CoV-2 emerged in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, spurring the worst pandemic in a century.

His central argument: that a virus emerging in a city with a major coronavirus lab is too much of a coincidence to be unrelated.

“There’s been an outbreak of chocolaty goodness near Hershey, Pennsylvania. What do you think happened?” Stewart asked. “Oh, I don’t know, maybe a steam shovel mated with a cocoa bean. Or it’s the fucking chocolate factory!”

Stewart may be right, but so far there’s no evidence for it. “In the case of SARS-CoV-2, there are multiple scenarios that could, in principle, explain its origin,” said a June 15 statement from the presidents of the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine. Such scenarios include the virus spreading naturally — most likely from bats, possibly through an intermediate animal — to humans, or it could be connected to laboratory work.

As is the case for UFOs and Havana syndrome, all the scientific evidence behind the different COVID origin theories is circumstantial. First is history: The SARS outbreak in 2002 emerged in a city in China’s Guangdong province, about 1,000 miles away from the cave in the southwestern Yunnan province where, 15 years later, horseshoe bats were found carrying genetic links to that coronavirus. But signs emerged relatively quickly that civets sold in wet markets were the transmitters of the disease. Similarly, in the MERS outbreak in 2012, camels quickly turned out to be the carriers of that coronavirus.

Given the similarities between SARS, MERS, and SARS-CoV-2, many scientists thought an animal was the most likely culprit for the December 2019 outbreak. But what’s needed to clinch that theory is finding an animal infected then with a 99% genetic match to the SARS-CoV-2 virus. That hasn’t happened yet.

That leaves open another possibility with increasingly ardent adherents: that the coronavirus escaped from a lab. Rather than being a unified theory, the “lab leak” idea encompasses many possibilities, including either an accidental release (of a virus engineered in a lab or collected in nature) or a deliberate one (of a Chinese bioweapon).

At the center of this set of theories is the Wuhan Institute of Virology — where a team led by virologist Shi Zhengli has conducted research into finding and cataloging new bat coronaviruses. Shi has also drawn scrutiny for participating in controversial gain-of-function research, led by University of North Carolina scientists, genetically altering bat coronaviruses to see if they could infect humans. Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky has called this approach “juicing up super-viruses.” Shi has also been criticized for her conflicting statements over her team’s collection of bat viruses that may have infected a group of miners in a Chinese cave in 2012.

The biggest impediment to finding any answers so far has been Chinese secrecy. A recent study by China and the World Health Organization into the origins of the coronavirus was not given access to raw data or samples and ultimately came up empty, but it still ranked the possibility of a laboratory escape as “extremely unlikely.” That led even the WHO’s chief to call for further investigation. Scientists have since also pushed for more investigation, alongside the US government and 13 other countries.

In the absence of hard scientific evidence, oblique references to intelligence reports and leaks have instead been grabbing headlines.

One of the earliest and most vocal adherents to the lab leak theory was former president Donald Trump, who began blaming Chinese leaders for the “China virus” in March 2020. A month later, he said he had “a high degree of confidence” that the coronavirus had escaped from a lab, based on intelligence he couldn’t disclose. Mike Pompeo, then the secretary of state, backed up that assertion, saying “enormous evidence” indicated that the virus originated in a Wuhan lab. Both men claimed they were “not allowed” to reveal what this evidence was, and it’s never surfaced.

A series of news reports and statements have since made clear that the Trump administration sought out evidence of a lab leak. Parts of the State Department allegedly pushed to find China in violation of international bioweapons conventions. That effort culminated in a “fact sheet” released on Jan. 15, 2021, titled “Activity at the Wuhan Institute of Virology.”

The fact sheet began by saying the US government has not determined “whether the outbreak began through contact with infected animals or was the result of an accident at a laboratory in Wuhan, China.” But it went on to raise questions about “several” sick lab personnel who were hospitalized around the time of the theorized first emergence of the virus, and whether the lab performed any gain-of-function experiments on RaTG13, the bat coronavirus linked to the miners’ deaths. No definitive evidence has been released on these points, and Shi has disputed the suggestions. The State Department also said the Chinese military had collaborated with the Wuhan Institute of Virology and ended by calling for “complete, transparent access to the research labs in Wuhan.”

President Joe Biden has since requested a review on the origins of COVID-19, stating that two US intelligence agencies now lean toward a natural origin for the virus and one leans toward a lab leak.

“That is three agencies out of 18 US intelligence agencies,” Rofer said. “So that means the other 15 said, ‘We don't have enough information to go one way or another.’”

Also like UFOs and the neurological symptoms first identified in Havana, the language around a “lab leak” is so vague that it has fueled more confusion and conspiracy. It puts disparate possibilities — from an accidental release to a deliberately engineered bug — on equal footing.

Finally, the politics surrounding the lab leak make the other mysteries look like a game of tetherball. China’s secrecy, whether it’s the habit of an authoritarian country or something more suspicious, has alarmed scientists and spies alike. And Republican lawmakers — emboldened in part by Trump’s early statements — have turned the mystery of where COVID came from into one of the most politicized scientific questions of the pandemic.

“You can’t prove a negative.”

In an era of QAnon, when a significant percentage of the US population believes that the last election was rigged, perhaps it’s no wonder that visions of aliens, Russian spy attacks, and the possibility of a Chinese bioweapon have made headlines.

Under paranoia’s shade, all the sinister explanations for UFOs, Havana syndrome, and the pandemic fester on the lack of evidence to prove or disprove them. “We actually have to have evidence to prove anything,” Rofer said. “You can’t prove that it’s not a microwave weapon. You can’t prove that it’s not a UFO. You can’t prove it’s not a lab leak. You can’t prove a negative here.”

Without any evidence, the shadowy world of US intelligence reports is unlikely to offer any illuminating answers, said secrecy expert Steven Aftergood of the Federation of American Scientists. “It is the role of intelligence to identify and characterize threats to the nation and to sift what is likely true from what is probably false,” he said.

“But the public has gotten very little useful or meaningful information from our intelligence agencies,” Aftergood added. “They could do better.” ●