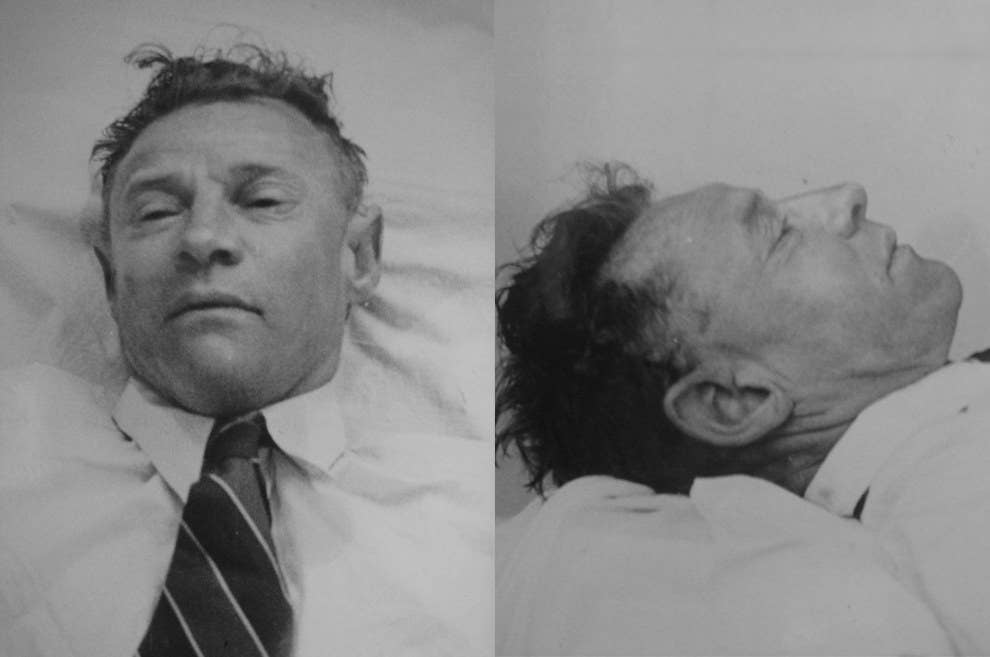

The dead man reclined against a beach wall that morning in a suit and tie, with an unlit cigarette resting on his collar, as if merely dozing on the pristine sand.

“I beg to report that on the morning of the 1st December, 1948, an unidentified body of a man was found on the beach of Somerton,” began the police report. Investigators found no missing persons, immigrants, or ship’s deserters to explain the “Somerton Man,” one of Australia’s most enduring cold-case mysteries.

Now, after nearly seven decades, DNA has turned up some answers — and more questions. A forensic scientist in California has discovered a genetic link that pinpoints the man’s origins to the US East Coast, with growing hopes that additional searches will uncover closer relatives, and finally give the man a name. The scientist, Colleen Fitzpatrick, will present these results next week at the International Symposium on Human Identification in Minneapolis.

“DNA is going to make the ultimate difference in this case,” Fitzpatrick, a forensic genealogist with Identifinders International in Fountain Valley, California, told BuzzFeed News. “We are getting closer to an answer.”

The clues to the “unparalleled” mystery of the Somerton Man have baffled investigators from the day he was found, sparking a tabloid fascination that's still going strong.

The man died on the beach with his feet crossed, with no signs of struggle or distress to mark his end. Passersby had mistaken him for a drunk. The labels had been clipped from his clothing. His pockets held chewing gum, combs, and unused bus and train tickets.

An autopsy failed to find a cause of death, and noted that the man was in his forties with a fit physique. (A coroner’s assistant said the man possessed strong and high calf muscles.) The coroner suspected that the man had been poisoned or killed himself, but couldn’t find any evidence for this theory.

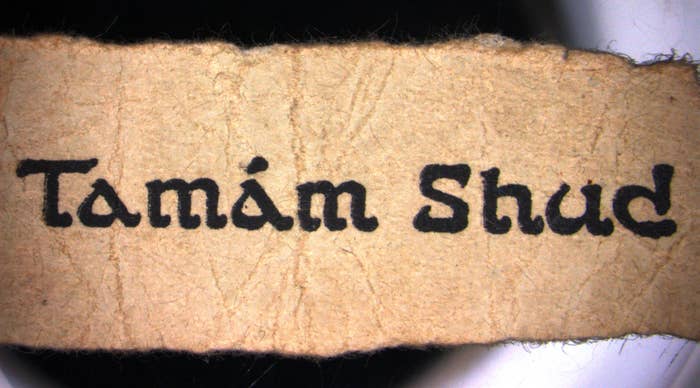

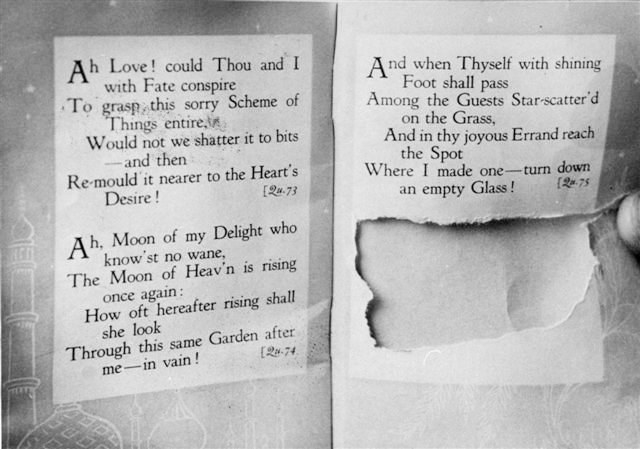

Investigators did find one bizarre clue: a scrap of paper tucked in the man’s watch pocket, printed with the words “Tamám Shud,” which means “finished” in Persian. The scrap came from the last words of the last page of The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam, an 11th-century poetry book about life’s transience.

Police recovered the man’s suitcase from the train station (a spool of thread inside the case matched the thread used to repair one of the man’s pockets), yielding more incomplete clues. It held only a few tools, a shaving kit, and clothes, including a coat with feather stitching that bespoke US tailoring. It also held Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit gum, which American men chewed back then, but Australian men didn’t. The Australian police consulted FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover, but the agency couldn’t find a fingerprint match of the man.

The Cold War was on, leading some journalists to later speculate that the Somerton Man was a murdered spy, either American or Russian.

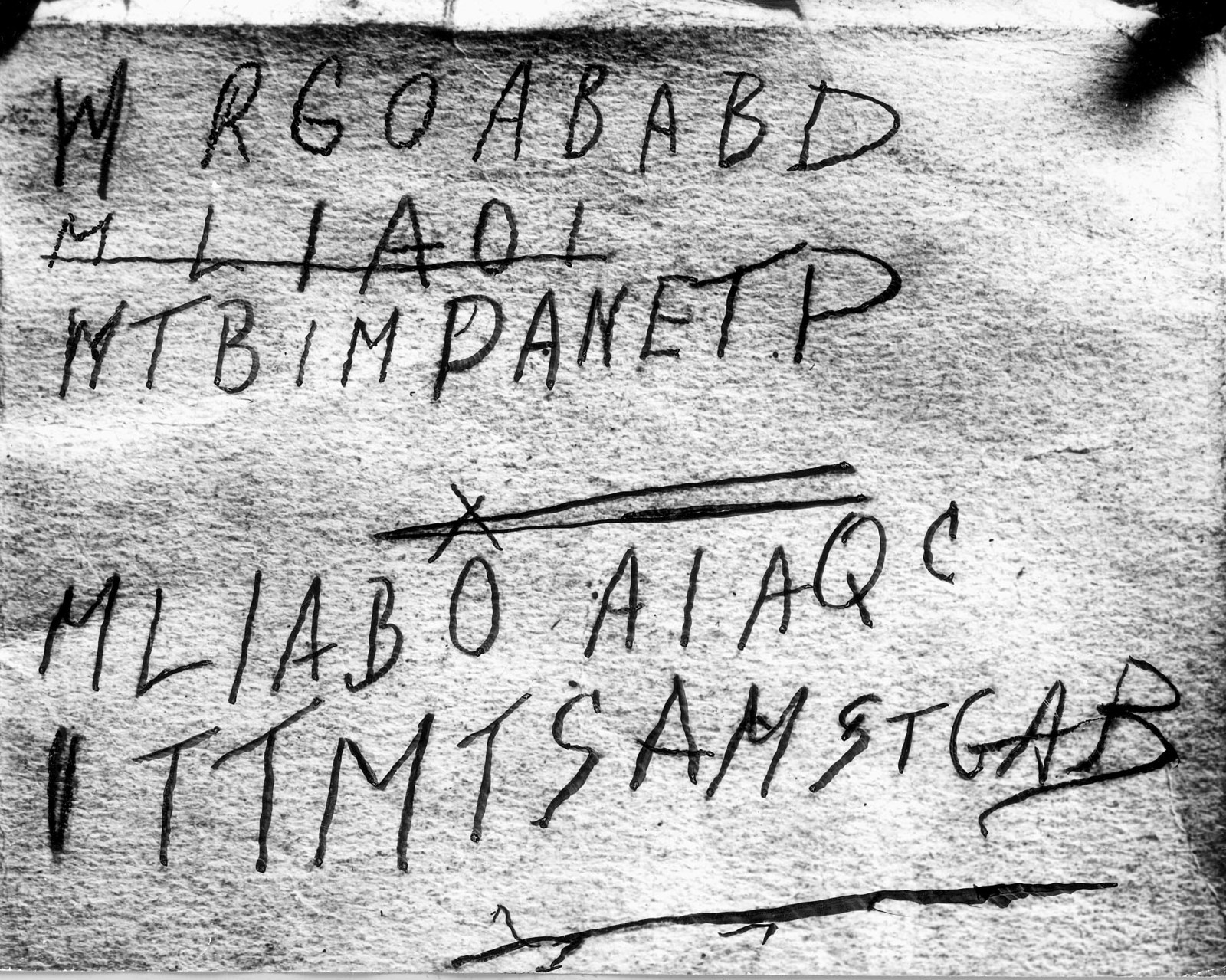

The spy theory hinged on a copy of The Rubáiyát that had been dropped in a man’s car around the time of the Somerton Man’s death. (The car’s owner dropped the book off at the police station, saying he didn’t know how it got there.) The last page of the book had been torn out and replaced with a list of random letters — a code, perhaps.

In 2011, students from Australia’s University of Adelaide found that the letters matched patterns of the first letters of words in typical English sentences. But that didn’t explain anything about their connection to the Somerton Man.

“I try to keep an open mind on who he was,” Derek Abbott, a biomedical engineer at the university who has studied the mystery for seven years and who led the student team, told BuzzFeed News.

DNA, Abbott said, is a key to solving the mystery. “I’m not so interested in how he died, but giving him his name back is the most important thing.”

DNA preserved in the man’s teeth or bones, Abbott knew, could link him to family members in genealogy databases worldwide. But the attorney general of South Australia has twice denied Abbott’s request for exhumation, arguing that the mystery probably wasn’t a criminal case, but merely a matter of curiosity.

Chasing another avenue, Abbott turned back to the copy of The Rubáiyát that had been found in the car, which had a phone number scrawled on its back cover. At the time, the number belonged to a 27-year-old local woman named Jo Thomson. When police originally contacted her, she denied knowing the dead man. And she remained coy about the man’s identity, despite decades of speculation, until her death in 2007.

Abbott started asking her family about the case. She had a son, Robin, born in 1946, who had two distinctive facial features — an oddly shaped ear, and two missing incisors that left his canine teeth parked right next to his two front teeth — that Abbott learned were shared by the Somerton Man. Robin Thomson was also a dancer in the Australian Ballet, blessed with strong calves. All of those things, Abbott thought, pointed to Robin as the son of the Somerton Man.

Robin Thomson died in 2009, but he was survived by his ex-wife, Roma Egan, and a daughter, Rachel. Abbott wrote a letter to Roma, asking if she knew anyone who resembled the Somerton Man. Yes, she replied: her ex-husband. Abbott went to see her and convinced her of the genetic link, which is how Fitzpatrick, the DNA genealogist, entered the investigation.

Abbott had heard of Fitzpatrick’s work tracking down people’s relatives, including a boy who died on the Titanic and a Colorado man living with amnesia in search of his family.

If Rachel is the granddaughter of the Somerton Man, then she inherited about 25% of his DNA. Fitzpatrick compared DNA from Rachel and her mother to identify which portions of her genome came from her father. Then the scientist ran those segments through massive DNA databases (maintained by genealogy companies such as Ancestry.com) to try to find out more about her father’s father — the suspected Somerton Man.

The genetic records of individuals in these databases, along with their family trees, allow researchers — or long-lost cousins — to trace people’s ancestry back many generations. Certain genetic marker combinations tie together distinct families and places. (A recent study of living heirs of French royalty identified the genes of the kings of Versailles, for example, as well as calling into question a purported head of King Louis XVI.)

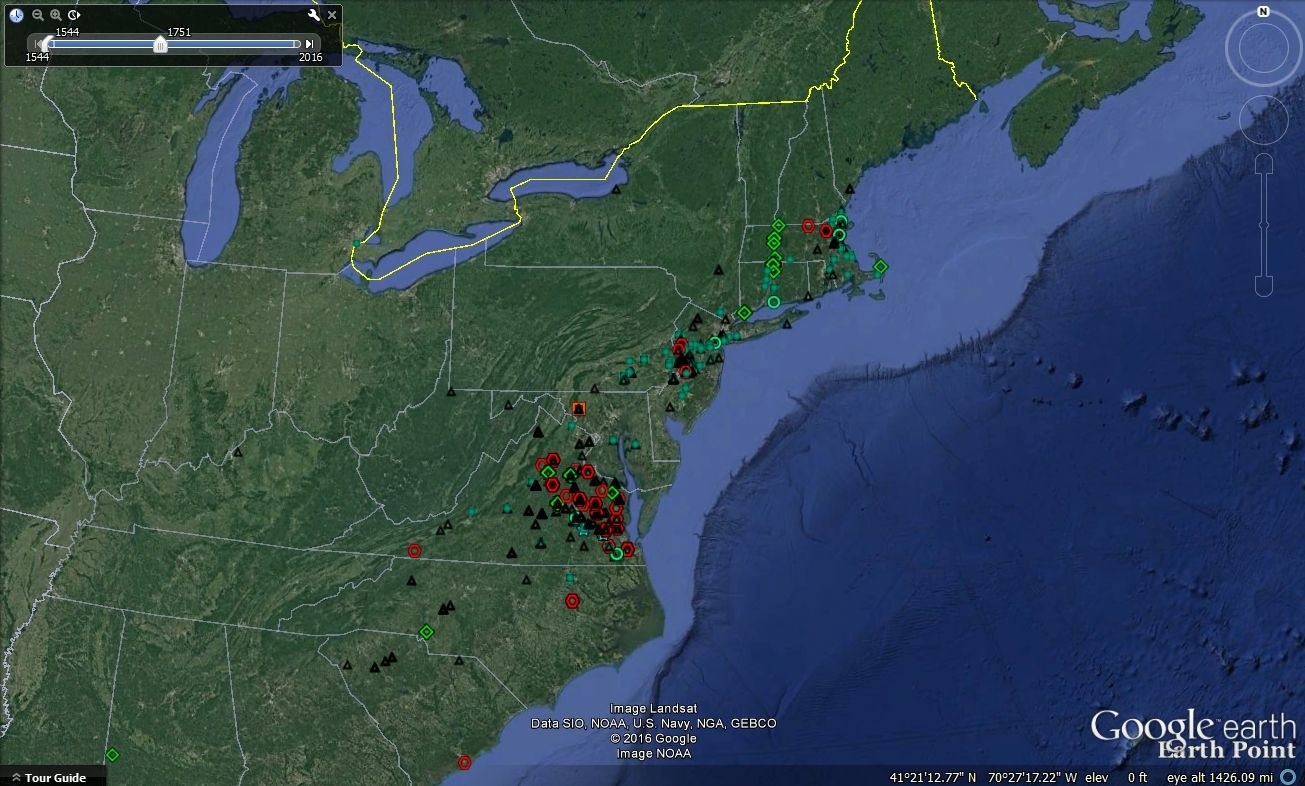

As Fitzpatrick will present at next week’s meeting, Rachel’s paternal line traced back to the Mid-Atlantic states of the US, centered around Virginia.

“We see traces of Native American ancestry and chromosomes linked to relatives of Thomas Jefferson,” Fitzpatrick said. The Native American genes tied to the Somerton Man also come from tribes living along the East Coast, she said. “That puts Mr. X’s ancestry, with some authority, in America.”

More and more people are adding their genes to these databases every day, making them more reliable at ferreting out connections between families. “DNA is basically a waiting game,”Abbott said. More links to the Somerton Man’s DNA could emerge any day, further pinning down his family origins.

Of course, this is only true if Rachel is indeed the Somerton Man’s granddaughter. To be more sure about that would require exhumation of his corpse and either genetic testing of any intact tissue or chemical analysis of dental enamel, which can reveal where someone lived when their teeth formed. Despite the two previous denials, Abbott is leading calls for a petition to exhume the Somerton Man.

In Australia, exhumation requests can be legally made either to contest a will or to find a soldier lost in war. The Somerton Man fits into neither category.

“If it is likely that the perpetrator of a murder is deceased, then there is a decent ethical case that it serves no purpose to pursue the legal case any longer,” genome expert Jared Roach of the Institute for Systems Biology in Seattle, who was not part of the investigation, told BuzzFeed News. “However, I think a good ethical case could be made along the lines of trying to return an unidentified body to its family,” he added — similar to an unknown soldier.

"You don’t have to be a spy to be secretive.”

Abbott and Fitzpatrick don’t think the man was a murder victim or a spy. “You can explain any weird thing by saying he was a spy,” Abbott said. But “you don’t have to be a spy to be secretive.”

Maybe he was involved in the black market for scarce goods, like cars, which was common in the postwar years and would explain his secretiveness (and a sea cargo stencil brush found with his belongings). The scientists believe that he went to Adelaide to see Jo Thomson, then died by happenstance on the beach wall, perhaps by “positional asphyxia,” where someone passes out in a position that cuts off their breathing. (Strange asphyxiation cases litter the forensic science literature, such as the 2010 report of a man who died after falling asleep inside three truck tires or the 2006 case of a man strangled by automatically closing supermarket doors.)

“Perhaps if you took away anyone’s ID and left only a few clues behind, we’d all seem extraordinary and mysterious,” Abbott said.

The final DNA twist in the Somerton Man case comes from Abbott himself. In 2010, after meeting Rachel, the suspected granddaughter of the Somerton Man, he fell in love. “This is how I met my wife,” he said, with a somewhat bemused air. “It just kind of happened.”

Today, they have three children, all of whom may carry some of the genes of the Somerton Man.

“It’s one of those crazy things,” he said. “Life is sometimes stranger than fiction.”

CORRECTION

The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam is an 11th-century poetry book, not a 20th-century book.