WASHINGTON — As President Donald Trump and Congress weigh e-cigarette bans amid an outbreak of deadly lung injuries, a fight has erupted over whether vaping supporters online are real people — or bots funded by an industry under attack.

The fight was sparked by a controversial report released two weeks ago by the Public Good Projects, a public health nonprofit. Its analysis — which looked at 1,288,378 tweets related to e-cigarettes or tobacco sent between Feb. 1 and June 1 — concluded that nearly 80% were likely generated by bots, or automated accounts, “posing as passionate pro-vaping individuals.” The findings have been called into question by experts skeptical about its methodology.

The bots report sparked panic among public health officials who are suspicious that the vaping industry, backed by Big Tobacco, is using shady marketing tactics to sway public opinion with misinformation about the dangers of nicotine. But it has also triggered furious backlash online from e-cigarette users concerned about losing access to potentially life-saving vapes. This group has flooded the #NotABot hashtag with conspiracy theories and political threats aimed at the Trump administration, which is grappling with a proposed ban on flavored e-cigs.

Paranoia about the lessons learned from the 30-year-old battle with Big Tobacco loom large on both sides as public health officials worry that vaping companies are borrowing from its playbook, and vaping users fear being driven back to smoking cigarettes.

The findings made headlines when they were first reported by the Wall Street Journal, which linked the report to a congressional committee holding a hearing that week investigating the four major sellers of e-cigarettes, Juul Labs, Fontem Ventures, Japan Tobacco International USA, and Reynolds American. The hearing was actually a look at legislation aimed at curbing youth vaping, rather than corporate behavior. But in August, the committee requested a “list of all social media influencers the companies have paid to market their products and any handles and usernames for social media bots that the companies use to market their products.”

Rep. Frank Pallone of New Jersey, the chair of the Energy and Commerce Committee, linked the inquiry to a nationwide outbreak of severe lung injuries under investigation by the CDC — now standing at 1,604 cases and 34 deaths — to the vaping of THC oil from the black market. Congress was already alarmed by reports of a sharp increase in e-cigarette use among teens. Twenty-one percent of high school seniors had reported vaping in the last 30 days. States such as Massachusetts and Michigan have instituted full or partial vaping bans as a result.

The reliability of the bots report was soon called into question. On Oct. 15, Amelia Howard, a University of Waterloo graduate student and vaping advocate, tweeted that a draft version of the report shown to her by a reporter had listed five illustrative “bot” accounts in a middle section. In at least four cases, those so-called bots were actually people she knew or had met.

Over a week ago the Wall Street Journal asked me to comment on the report that occasioned this story. Sadly none of my comments made the cut. But that's ok, I'm happy to repeat what I told WSJ (and more!) on twitter in this thread you're gonna want to read https://t.co/B8E9WILc0o

That six-page section was cut from the final report when it was released to the public, a move that Howard suggested was to hide its flawed findings. She called it part of a larger “moral panic” aimed against e-cigarettes by public health officials and scientists. “Tobacco control is a very political field and is morally motivated,” Howard told BuzzFeed News.

In defense of the report, Joe Smyser of the Public Good Projects told BuzzFeed News, “What we were really looking for is automation” by Twitter accounts, which might encompass people setting their accounts to automatically retweet certain hashtags. So while real people might own the Twitter accounts, their use of automated tools might leave them flagged as a “bot,” what Smyser called a “cyborg.”

“There is a great deal of messaging that e-cigarettes are safe, nicotine can’t poison people, and that public health authorities are lying,” Smyser said.

The write-up of five accounts was removed when the group learned the accounts could still be identified despite attempts to redact their names, Smyser said. The point of the report was to show how automation helps sell e-cigarettes and how the practice outweighs public health messages that urge people not to vape — not to attack specific accounts.

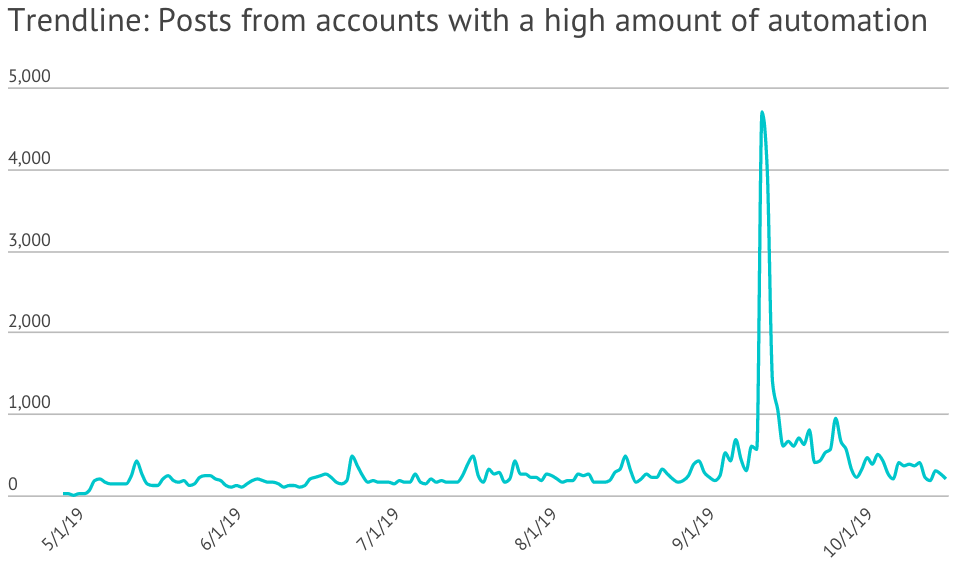

“The recent talks about banning e-cigarettes and the vaping illnesses have provided automated accounts with fuel,” Smyser told BuzzFeed News. “This is just the new normal now, and the public health community is behind the eight ball on catching up.”

Other experts say that the numbers in the report sound reasonable based on prior research, but called into question the study’s poorly described methodology for detecting automation.

In a 2017 study cited by the report, Jon-Patrick Allem, an assistant professor of research preventive medicine at the University of Southern California, analyzed more than 6 million tweets related to e-cigarettes with computer code posted online to allow other people to check the approach, relying on about 1,000 characteristics of bot accounts to ferret them out. That study found about 70% of tweets about e-cigarettes came from social bots.

The Public Good Projects report’s results rested on about 100 signs of automation, according to Smyser, such as automatic retweets in response to hashtags and never tweeting original content, to rate 80% of accounts it saw as bots. Those numbers don’t sound unreasonable in 2019, said Allem, especially as scrutiny around vaping has skyrocketed amid the lung injury outbreak. But without detailed methodology describing how the researchers found this phenomenon getting stronger, the results can’t be taken at face value. That “isn't how we do it in scientific studies," Allem said.

Smyser said his group is planning to submit the report to a scientific journal to more rigorously address such concerns, arguing that the original paper was “meant for general readers, not scientists.”

7/8 If you’re looking for info on #ecigs & #vaping, pro info often really is easier to find, because of a united front. Here’s a chart showing the recent increase in hashtags used by pro-vape advocates

“Bots are really pretty sophisticated now, compared to 10 years ago,” Allem said. The online world is filled with a bewildering grab bag of vaping stores that automatically post sales announcements, advocates who auto-respond to hashtags, and genuine bots that steadily disperse misinformation, he said, intermingled with real people who turn automatic behavior on and off in random fashion.

Bots "are becoming harder to detect," he added.

This round in the fight over the future of vaping dates at least back to September 2018, when the FDA, in the largest coordinated investigation in the agency’s history, issued more than 1,300 warning letters and fines to stores that illegally sold Juul and other e-cigarettes to minors during a self-described “nationwide, undercover blitz of brick-and-mortar and online stores.”

A month later, the National Youth Tobacco Survey reported a sudden increase of more than 1.5 million high school and middle school students in the US who had used an e-cigarette in the previous month, taking the total up to 3.6 million people and noting a significant increase in flavored vapes.

“These new data show that America faces an epidemic of youth e-cigarette use, which threatens to engulf a new generation in nicotine addiction,” said Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar in response. Suspicion of fakery in Juul’s marketing campaign, and among purported vaping supporters, emerged from Allem’s 2017 study and a long-standing, merited distrust of the tobacco industry.

In the 1950s, tobacco companies settled on the “Doubt is our product” advertising strategy to delay regulation. Over the next four decades, the tobacco industry employed front groups, fake scientists, and lobbyists to sow confusion about the links between tobacco and lung cancer, heart disease, and other deadly illnesses. The World Health Organization has called the industry effort, revealed through lawsuits in the 1990s, “a relentless defence of its economic interests,” that put profits ahead of public health.

The descendants of those same companies are now heavily involved in selling e-cigarettes, with industry leader Juul headed by a CEO, K.C. Crosthwaite, installed last month from Altria (formerly Philip Morris Companies), which owns 35% of the vaping firm. Lobbying efforts like Juul’s “Project Switch” — which sought to connect customers with a public relations firm that specializes in “grassroots” political messaging for business clients to push against a New York state ban — have public health officials suspicious that a history of fake front groups is repeating itself.

Ironically, foes of vaping fans have their own suspicions of fakery. There was a blowup in July 2018 over some 500,000 anti-vaping comments submitted to the public comment section of a proposed FDA “Regulation of Flavors in Tobacco Products” that the pro-vaping website RegulatorWatch decried as “spam,” or fake comments meant to overwhelm the 22,000 pro-vaping comments submitted to the docket.

“The FDA is aware that a number of auto-generated comments were submitted to the docket for the advance notice of proposed rulemaking on flavors in tobacco products,” the FDA’s Stephanie Caccomo told BuzzFeed News by email. “However, as noted on regulations.gov, the comment process is not a vote — agencies make determinations for a proposed action based on sound reasoning and scientific evidence.”

I am just one of over 10 million adult smokers who have quit by switching to legal FDA-regulated nicotine e-cigarettes. I plan to attend the first-ever US national Vaping Rally in Washington DC on November 9, 2019. DO YOU? @LegionVaping @thr4life @Vapingit @whycherrywhy

The brawl over whether the support for vaping comes from real people or astroturfing (fake grassroots efforts invented by companies or politicians), looks familiar, drug policy expert Leo Beletsky of Northeastern University told BuzzFeed News. The two sides — public health officials concerned about vaping teens, and ex-smokers scared to death of vaping bans — are talking past each other with language borrowed from the 30-year fight over cigarettes, he said.

“When the conversation shifts to talking about any addictive substance use by teens and kids, we totally lose our minds,” he added.

Congressional hearings about vaping regularly feature laments from lawmaker parents and grandparents about vaping among their offspring, even as public health officials struggle to explain that millions of adults have shifted from smoking with the help of e-cigarettes.

“Really there is no honest conversation going on here,” he said.

Tobacco, abetted by its addictive nicotine ingredient, kills more than 7 million people a year worldwide. On the public health side, e-cigarette firms are investors, owners, or peddlers of that same nicotine, making it easy to see claims by the vaping industry and its fans as just another industry smoke screen for hooking teenagers. Juul’s high-strength nicotine pods — packed with 59 milligrams of nicotine per milliliter, more than 2.5 times stronger than legal limits on nicotine in the United Kingdom — flaunts a strategy of tapering nicotine levels in tobacco products called for by public health researchers to cut teen smoking since 1994.

“Nicotine levels in e-cigarettes are quite harmful to the developing brain, which doesn’t stop developing until age 25,” Anne Schuchat, principal deputy director of the CDC, told reporters in a news briefing on Friday. In a statement on the outbreak, the agency advises former smokers and anyone else addicted to nicotine using e-cigarettes to "consider utilizing FDA-approved nicotine replacement therapies."

Against this, a few voices have pointed out that banning legal e-cigarettes could drive users back to cigarettes or to the illicit market for vaping liquid, which has already been linked to the deadly outbreak.

“THC is just a proxy for illicit,” said Beletsky. “It’s the illicit part that matters.”

Perhaps in response, the pro-vaping world of social media has been “very combative,” said Allem, who studied sentiments voiced on Twitter about vaping liquids in a 2018 study. He found that most posts were about sales (29%) and flavors (24%). Health risks from nicotine were rarely mentioned (6%) and “Quit Smoking” was almost nonexistent (less than 1%).

Conspiracy theories have also increased along with the combativeness. One popular theory, #MSABloodMoney, references the 1998 Master Settlement Agreement that limited cigarette advertising and steered tobacco industry revenue to states to pay for tobacco-related diseases in perpetuity. The conspiracy theory — which has also been touted by Grover Norquist of Americans for Tax Reform, an anti-tax activist hugely influential within the Republican Party — paints parents and doctors worried about teens vaping as being motivated by greed for cigarette tax revenue.

The government tax collectors make more money on every pack of cigarettes than the farmers, manufacturers, retailers of cigarettes--combined. Of course, the tax and spend liberals want to stop people from moving to vaping. They want your money. Could care less about your health

Norquist’s involvement shows how the political side of the #NotABot furor adds to its intensity. In September, the Trump administration shocked the vaping industry by saying it was moving to ban flavored vapes nationwide. “A lot of people think it’s wonderful,” Trump said to reporters. “It’s not a wonderful thing.”

That has led to another hashtag, #WeVapeWeVote, sweeping Twitter amid threats that vaping fans turning against Trump in battleground states such as Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, per Axios, could cost him the 2020 election. A “WeVapeWeVote” protest took place before a Trump rally in Dallas, and news reports emerged on Friday that the president’s ban was losing steam in the White House, causing him to retreat from a full flavor ban to one that would spare menthol and mint flavors.

The Vapor Technology Association launched an ad campaign this month on Fox News to influence Trump to halt his ban. Sean Hannity vaped on his show in 2017 during a commercial break, and listeners have complained about vaping ads supporting his radio show.

Underneath the fights over vaping on Twitter, there’s little doubt that Juul and its lookalikes are sold by businesses that aim to maximize their sales, health policy expert Kar-Hai Chu of the Center for Research on Media, Technology, and Health told BuzzFeed News. Chu’s research, for example, has found that a quarter of all tweets by Juul were retweeted by teenagers, showing who was targeted in its lifestyle ads. Touted by Instagram and YouTube influencers popular with teens and young adults, Juul’s marketing has cast doubt on its self-proclaimed public health benefits.

“Flavors are what get kids interested in e-cigarettes, a lot of evidence shows,” said Chu, explaining the interest in flavor bans by states.

Rather than an outright ban, said Beletsky, the e-cigarette market requires sensible, nationwide regulation aimed at letting people who genuinely benefit from vaping continue while also curbing teens' access to the products. Outlawing e-cigarettes will just drive people to the black market.

But he’s not optimistic, he added: “It’s very rare in drug policy where we use a scalpel. Usually we use a wrecking ball.”

CORRECTION

The name of the Public Good Projects was misstated in an earlier version of this post.