Fears of a major nuclear reactor disaster in the middle of the war in Ukraine took on a frightening possibility on early Friday.

With the world riveted to security camera views of a fire, and fighting, at Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, fears of damage to the reactors ricocheted around the globe. Ukrainian Foreign Affairs Minister Dmytro Kuleba tweeted that a disaster there “will be 10 times larger than Chornobyl!" By morning, the fire was extinguished, Russian forces had taken control of the plant, and its safety equipment was stable, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency. No radiation releases were reported from the facility. But the fear remains.

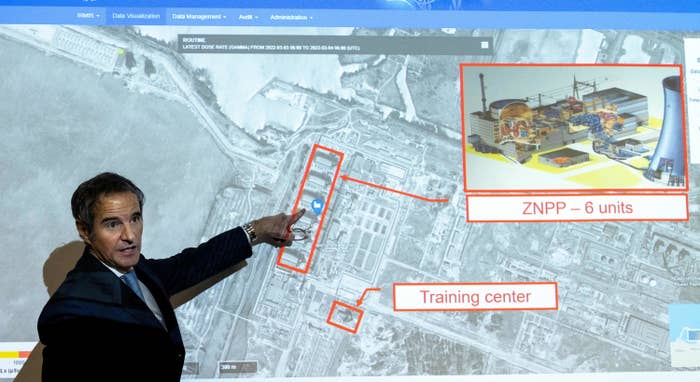

“We are in completely uncharted waters,” said Rafael Mariano Grossi, the head of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), in a Friday news briefing. “The physical integrity of the plant has been compromised with what happened last night,” Grossi said. “We, of course, are fortunate that there was no release of radiation and that the integrity of the reactors in themselves was not compromised.”

Grossi also offered to personally travel to Chornobyl (often transliterated from Russian as "Chernobyl"), the 1986 site of the world’s worst nuclear accident, to work out safeguards for the nuclear power facilities in the war-torn nation.

In the US, Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm activated the agency’s Nuclear Incident Response Team, and said the US Department of Defense and other agencies are closely monitoring radiation levels reported from the plant. She later expressed support for the IAEA’s calls to allow Ukrainian operators to continue working at Russian-captured nuclear facilities. The Energy Department team monitored instruments near the plant with IAEA and Ukrainian officials, according to the National Nuclear Security Administration spokesman Gordon Trowbridge, allowing them to report no leaks.

UPDATE: Russian forces are in control of the Zaphorizhizia nuclear plant, and we call on Russia to allow the Ukrainian operators to continue to operate safely – including allowing shift changes at both Zaphorizhizia and Chornobyl. 1/

Although nuclear reactors are heavily shielded, nuclear safety experts expressed serious concerns to BuzzFeed News about threats to these facilities during the war. Rather than a disaster on the scale of the 1986 Chornobyl meltdown, they warned of the potential for disasters more similar to 2011’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident. There, reactor cooling lost in a tsunami led to partial reactor meltdowns, explosions near spent fuel pools, and venting of radioactive gas. A 19-mile radius evacuation zone was created around the facility.

“Everyone has this mental picture of a tank shell hitting a reactor. But the real concern is cooling being lost,” said Cheryl Rofer, a retired Los Alamos National Laboratory nuclear chemist. “Obviously, there is war going on, which is horrible already, but having a war next to a nuclear reactor is not a good idea.”

Every nuclear reactor is a balancing act, where fuel rods are carefully kept just close enough together to generate the heat needed to generate electricity, while being continually monitored to prevent overheating, which would melt the fuel. This requires continuous cooling and a highly trained staff. The reactors themselves are covered with a steel shell and a heavy layer of concrete, expressly designed to withstand projectiles and plane crashes, and meant to contain the heat of the fuel melting down in a disaster. The Chornobyl reactors lacked this level of protection, which led to the open-air release of radioactive material.

Ukraine has four operational nuclear facilities, including Zaporizhzhia, according to the IAEA’s Power Reactor Information System database. According to Joshua Pollack of the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, there are at least two worrying scenarios that concern experts about nuclear power plants becoming engulfed in war zones:

• While reactors are very tough, their pools, containing used-but-still-hot fuel rods, aren’t. If a cooling pond is damaged and stops working, the water eventually boils off, and these fuel rods will catch on fire, spewing radioactive particles skyward. This was a major concern in the Fukushima disaster.

• If a reactor shuts down, loses access to outside power, and then loses its backup power, the coolant inside the reactor itself stops flowing. Shortly later, the fuel catches on fire inside the reactor and releases hydrogen gas. “As we learned in Fukushima, this is quite dangerous,” Pollack said. In that disaster, hydrogen explosions blew the roofs off reactor buildings. That led to radioactive gas releases and massive evacuations.

There appear to be at least three explanations for Russian forces attacking Zaporizhzhia at this moment in its week-old invasion of Ukraine, said Melissa Hanham, an open-source intelligence specialist affiliated with the Center for International Security and Cooperation at Stanford University. The first is simply in the fog of war, the Russian invasion force is taking over every facility in its path, which led to the firefight at the plant. The second is a deliberate bid to control a high-risk site, similar to the takeover of Chornobyl at the outset of the invasion. The IAEA has complained about staff at Chornobyl not having relief in monitoring operations there. A third explanation suggested by Ukrainian officials is that Russia intends to control and cut off electricity to the country as part of its invasion plan.

“If it is under Russian control, you would ask for some confidence-building by allowing the IAEA to have access and regular communication with whoever is running it, presumably Ukrainian staff,” Hanham said.

What does it feel like in Europe rn? Pediatricians in Vienna are giving out free iodine tablets. My best friend in Germany tells me her phone is blowing up w/moms trying to figure out right dosage for their kids if worst happens. Docs also telling parents to "seal your windows."

While shutting down the nuclear reactors in Ukraine now might seem like an obvious first safety step, the trouble is that nuclear power plants can’t turn off reactors like light switches. Cooling systems need to keep operating during a shutdown, as is reportedly occurring in two of the reactors at Zaporizhzhia (three others are already shut down, and one, remarkably, remains in operation). Ukraine's Radio Svoboda warned that the plant’s staff doesn’t want to “work at gunpoint” and may seek to flee the region to safety with their families.

“You want to make sure that those individuals, who are technical experts but also just humans are getting enough rest, are not under so much psychological strain from being under armed guard or worrying about their families that they’re not able to perform their job,” Hanham said.

As well, Ukraine still needs electricity, and the plants provide a significant fraction of its supply.

A related wartime concern is that backup cooling power generators at those facilities run on diesel, and the Russian military is reportedly running low on fuel. “One hopes they don’t steal that diesel to run tanks,” Rofer said. Presumably, she added, Russian officials should understand that any atmospheric release of radioactive gasses from a stricken nuclear facility in Ukraine would travel into Russia itself, given prevailing winds.

“It really is worth worrying about,” Rofer said. “Even if a disaster was more like Fukushima, that would be a terrible thing to add to an already terrible war.”

Zahra Hirji contributed reporting to this story.

UPDATE

The story was updated with a comment from NNSA's Gordon Trowbridge.