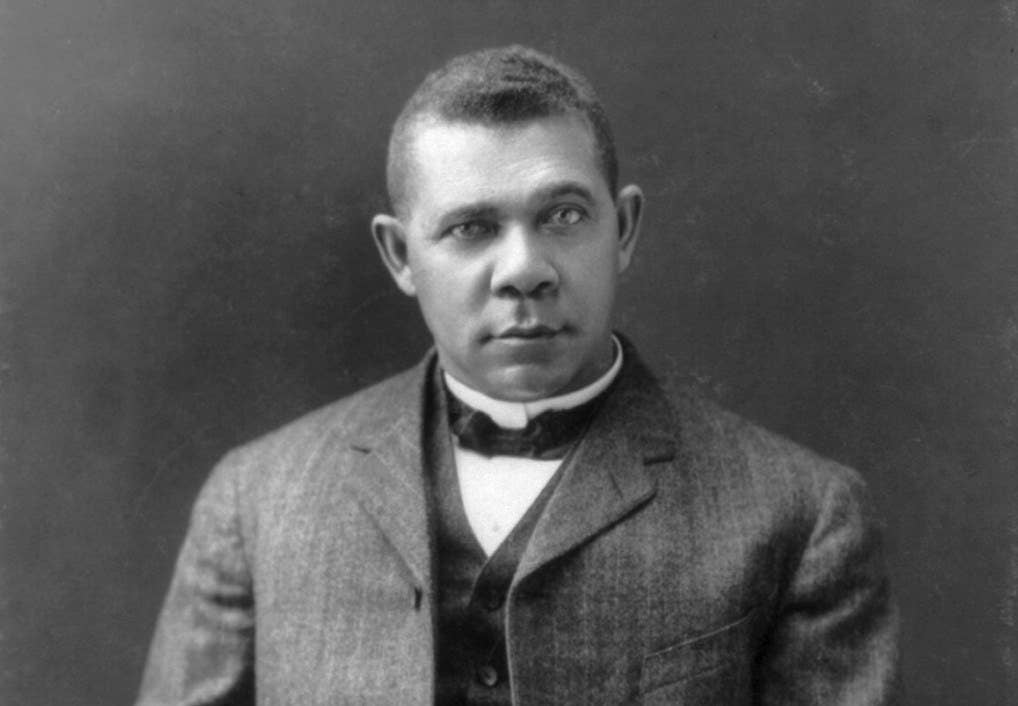

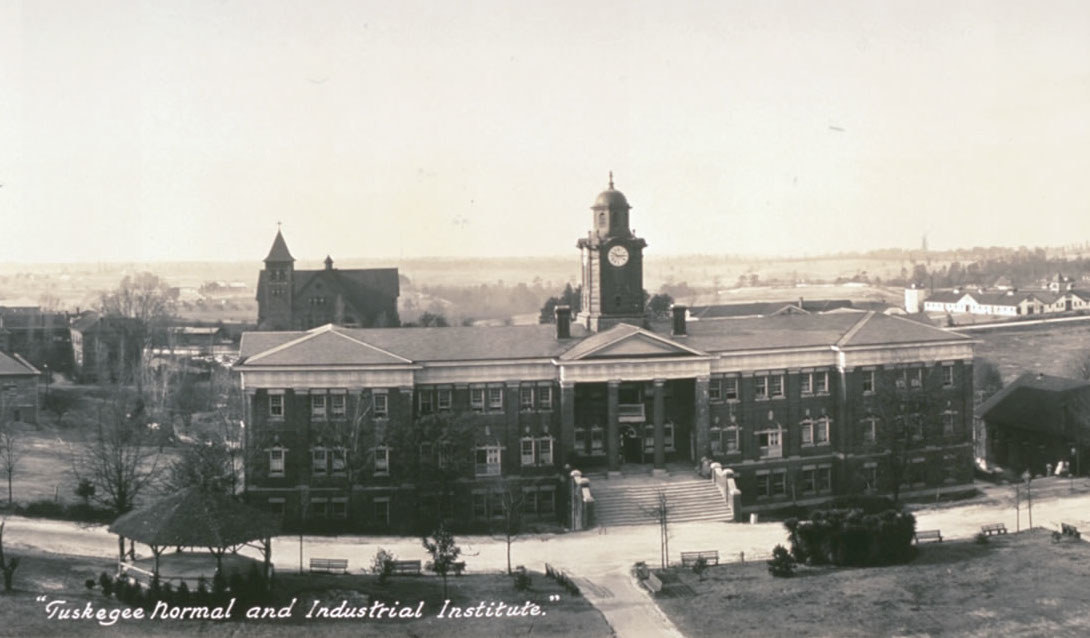

Booker T. Washington, president of Tuskegee University and a leading black figure in the early 20th century, invited eugenicist scientists bent on bolstering segregation to Tuskegee’s campus to measure its students.

The historically black school’s collaboration with racist scientists is revealed by historian Paul Lombardo in a new scholarly book, The Uses of Humans in Experiments: Perspectives from the 17th to the 20th Century, which comes out on Thursday.

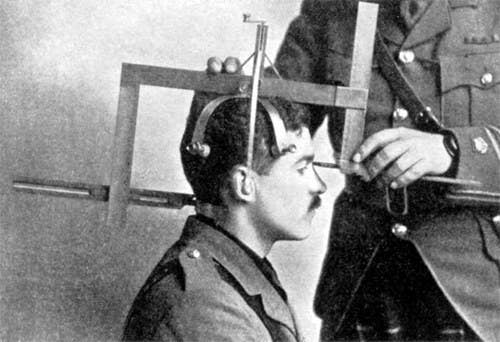

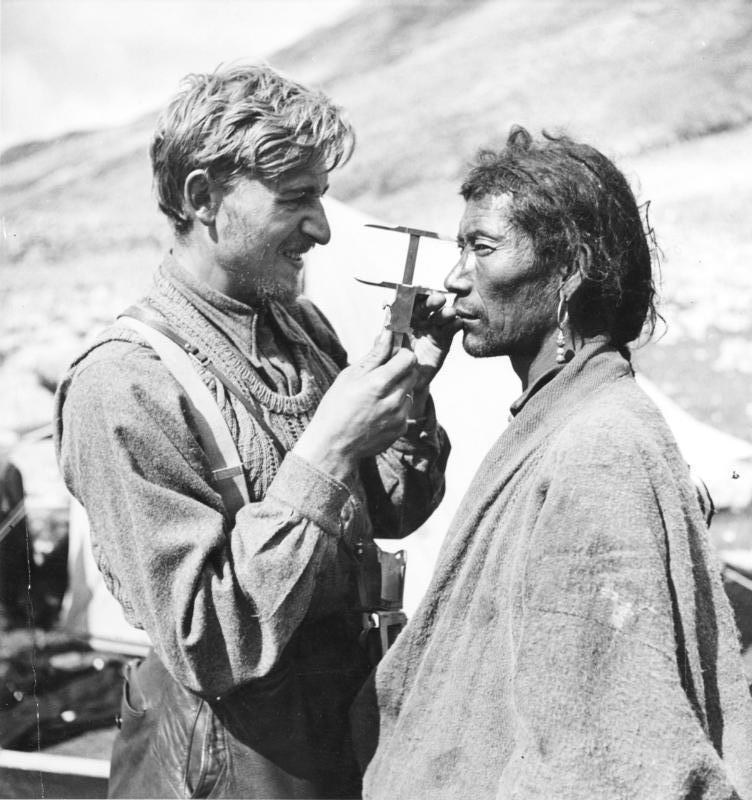

Washington first wrote to the eugenicists in 1913, though their studies didn’t begin until decades after his death. Between 1932 and 1944, Lombardo reports, scientists made “anthropometric” measurements — 131 different ones ranging from height and weight to nose shape and depth of ear pits — of more than 200 black Tuskegee students, and tracked their health over time, all in a misguided effort to define the “Negro race.”

Eugenicists of the era relied on calipers, rulers, and scales to define “pure” breeds of mankind. They also supported laws that eventually led to the involuntary sterilization of perhaps 60,000 poor and minority people in the U.S. in the last century, as well as the law blocking immigration of Eastern Europeans in the 1920s.

“They were all tied to this idea of racial purity leading to the betterment of humanity, which had terrible consequences,” Lombardo, a legal historian at Georgia State University, told BuzzFeed News.

On January 16, 1913, Washington wrote to Charles Davenport of the Carnegie Institution at Cold Spring Harbor, New York, one of the chief researchers in eugenics, inviting him to the college ”for study among our teachers and students.” Davenport agreed to visit but was delayed, and Washington died two years later, before Davenport ever came to campus.

Washington’s letter looks surprising to modern eyes, said Robert Norrell, a historian at the University of Tennessee and author of Up from History: The Life of Booker T. Washington. After all, Washington endorsed the views of Columbia University anthropologist Franz Boas, who denounced eugenics as "a dangerous sword," and argued people were pretty much the same, skin color aside, Norrell said. (Modern genetics has shown there is actually more inherited variation among people of African descent than in all the people in the rest of the world combined, which makes lumping them all together into one “race” ridiculous.)

“Washington said there was nothing inherent in biology keeping his people down,” Norell said. But it could be, he added, that Washington hoped measures of his students would demonstrate they were perfectly healthy and not about to “wither away,” an idea that was pushed by some eugenicists who saw blacks as inferior.

“Washington knew this idea was wrong and he may have hoped to refute it with data these white scientists would end up collecting,” Olivette Burton, a bioethicist at the humanitarian organization Sweet Nation, told BuzzFeed News. “In scholarship, you don’t always have the luxury of liking the people you work with, but you collaborate to get access to data and connections you can’t get any other way. That might have been the case with Washington.”

The Tuskegee student measurements were completely unconnected to the infamous 40-year Tuskegee study of 400 black men infected with syphilis who were deceived into thinking they were receiving treatment, when in reality the U.S. Public Health Service doctors were recording the natural course of their disease. But both Tuskegee efforts were similarly tied to eugenic ideology that blacks inherited “racial resistance” to syphilis, cancer, yellow fever, and other diseases, Lombardo said, “somehow setting them apart from other human beings in ways we can still hear people talk about today.”

Tuskegee’s cooperation with eugenicists might have been seen as nothing more than a way to bring a long-established type of science, human measurement, to an isolated college, Norell said.

“Tuskegee essentially had a tradition of taking the world as it found it, and trying to make something better out of it,” he said. “This was seen as a science, part of the times that are jarring to us now, but where racist presumptions were everywhere.”

Tuskegee representative Robert Blakely, the university’s vice president for advancement and development, declined to comment specifically on the experiments. “Science without ethics has reared its ugly head throughout history,” he said in a short emailed statement. Blakely also noted that Tuskegee’s involvement with eugenics came at a time when other universities, such as Harvard, were hotbeds of racist science.

It wasn’t until 1931, in the face of criticism about his later works claiming black inferiority, that Davenport tried again with Tuskegee, asking then-president Robert Moton to let the eugenicists collect measurements. Davenport was by then a well-respected scholar, associated with Harvard and the University of Chicago, as well as the National Academy of Sciences, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the U.S. Army.

Moton let him begin the research with two of Tuskegee’s coaches, who were already familiar with body typing since it was popular with physical education professors. Davenport ran the research for a year, before handing it off to one of his associates, Morris Steggerda, who had done similar eugenicist measurements in Jamaica and Mexico’s Yucatan. The football coach, Cleve Abbott, and the women’s track and field coach, Christine Petty, took the actual measurements.

“They clearly selected a lot of black athletes as ideal types,” Lombardo said. Mozelle Ellerbe, a record-breaking 100-meter sprinter, for example, was picked out for study.

The measurements were published in dozens of scientific studies, such as “An Anthropometric Study of Negro and White College Women” and “Potential Marital Selection in Negro College Students.”

Although the studies claimed that they had chosen students randomly, records held at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology in Washington, D.C. show they omitted students with “semitic” or “Indian” features, as well as noting “web toes” and “plenty of light people in the family.” (Although eugenicists were aware that American blacks were descendants of both Africans and Europeans, their fixed idea of “pure” races dominated the data they collected at Tuskegee and elsewhere, including colleges in Michigan and Virginia where they measured “European” students.)

Steggerda was not a loud racist like Davenport, and actually asked his study subjects for consent, unusual for a scientist at the time. Perry, the track coach, co-authored some of the studies with him.

“Washington and his Tuskegee colleagues were extreme ‘educational missionaries’ intent on using science — that is, pseudo-science — to try to realize an end to their black community’s vexing social problems,” Penn State’s David McBride, an expert on African American History, told BuzzFeed News by email.

“Black middle-class or ‘respectable’ sectors taking political and social stances and strategies that are at odds with the black working poor has been a common occurrence in black community life throughout black American history,” McBride added.

“What happened at Tuskegee was normal for the time, and is just part of the larger history of eugenics. But we should still be outraged by it,” bioethicist Keisha Ray of the University of Texas McGovern Medical School told BuzzFeed News. “Why were these measurements made? So someone could be ranked on top and someone else on the bottom.”

By the late 1930s, the walls were crashing down on eugenics, as audits showed much of the field’s data was cherry-picked and unreliable. A few years later, the eugenics programs of the Nazis brought the field into full disrepute.

Steggerda lost his job with Cold Spring Harbor in 1944 as eugenics was falling out of favor, and became a religious writer. His studies included fruitless searches for a “pure” Maya race, and reports claiming that race mixing in Jamaica produced “inferior” people.

He complained of “loneliness” at Tuskegee in his time there, adding that even though he had invited 50 of his “Negro friends” to his home, none had come. He died in 1955.

“There was a blindness there to the end, to seeing people as something besides their race,” Lombardo said. “It’s kind of sad.”