Capping an extraordinary day of vaccine politics, President Donald Trump questioned the vaccine timeline given by his own CDC director on Wednesday, calling the senior health official’s estimate that a coronavirus vaccine would not be available until 2021 a “mistake.”

“We’re going to have a vaccine within months, at most,” Trump said.

Wednesday’s events, which included a Trump campaign event on vaccines as well as a speech on the topic from former vice president Joe Biden, have public health experts fearing that Election Day politics threaten to undermine public trust in vaccines.

In the morning, the Department of Health and Human Services released a state road map — largely recapitulating presentations made last month at a CDC advisory committee meeting — for releasing vaccines, ahead of CDC Director Robert Redfield testifying before a Senate panel. Redfield testified that while limited doses for high-priority people could be available within months of a vaccine proving effective, its widespread availability to people everywhere would not come until 2021, most likely by summer or fall.

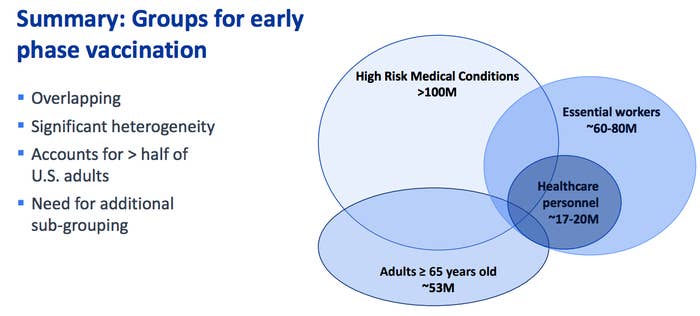

Openly disputing Redfield’s remarks in a press conference later on Wednesday, Trump and his new science adviser, Stanford University neuroradiologist Scott Atlas, instead promised that all high-priority individuals would receive a vaccine by January — a number estimated to exceed half of the US adult population in an August CDC vaccine meeting — and that 700 million vaccine doses would be available by the end of March.

Late in his news conference, Trump suggested that Redfield, who heads the agency tasked with distributing coronavirus vaccines nationwide, was unfamiliar with distribution plans for the shots.

“This is the tragedy of all this. Trump has consistently undermined scientists at federal agencies working to end this pandemic,” said Paul Offit, a vaccine expert at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Asked whether it was a good idea for the president to sandbag his own CDC director ahead of a vaccine rollout, he added, “I think that is a question that answers itself.”

“These are really good people at CDC and FDA, just the people you want in those places, who care a lot about the public’s safety. It’s tragic to undermine them,” Offit said.

The CDC did not respond immediately to a request for comment from BuzzFeed News.

With Nov. 3 less than 50 days away, the two presidential campaigns both held events devoted to coronavirus vaccines on Wednesday.

Two Republican physicians, one a member of Congress from Ohio, spoke in support of Trump's vaccine efforts on a call hosted by the president’s reelection campaign, criticizing Biden. On Wednesday afternoon, Biden hosted his own event in Delaware specifically devoted to vaccines, where he questioned the president’s record on science.

“I trust vaccines. I trust science. I don’t trust Donald Trump,” Biden said, complaining of fears that the president would “pressure the FDA” to approve a test without clear proof of its safety. “If there’s a vaccine, it should be totally transparent.”

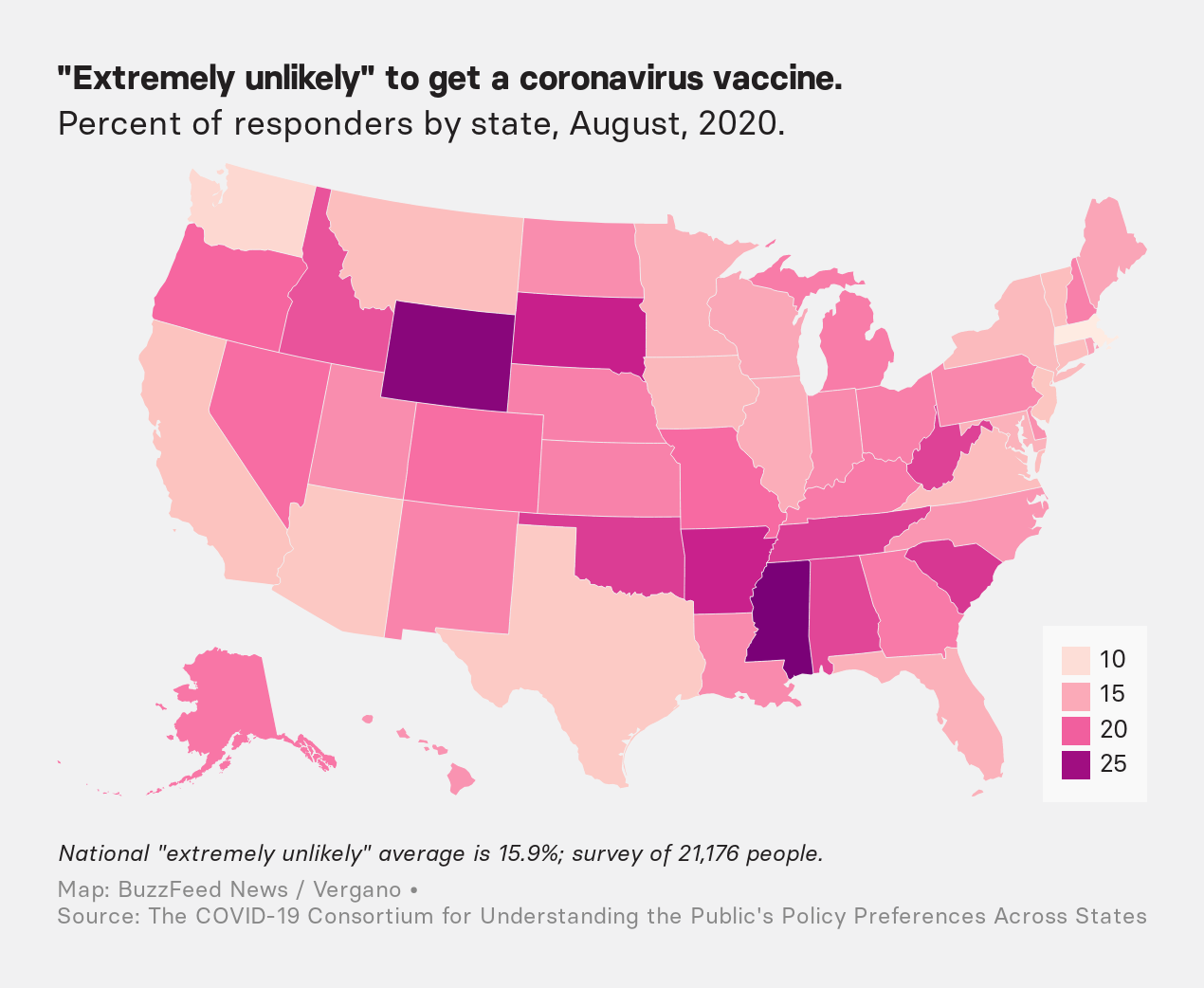

The day’s events come as people’s willingness to take a coronavirus vaccine has faded over the summer, public opinion polls suggest, and experts fear that such Election Day politics could threaten to sink those numbers even further. On Tuesday, a multi-university consortium released a 50-state survey of 21,000 Americans, finding that the number of people who said they were likely to get a vaccine dropped from 66% in July to 59% in August.

“That’s not a very impressive number,” said Matthew Baum, a Harvard public opinion researcher who led the polling report, saying respondents voiced fears of side effects from untested vaccines that rely on new technologies. “It’s an issue of trust.”

While the poll showed vaccine hesitancy from both the left and right, reluctance to get a vaccine is more pronounced among Trump’s supporters.

In the six months since the pandemic was declared, the president has repeatedly questioned the work of federal scientists, including National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases chief Anthony Fauci, pressuring federal endorsement of treatments like hydroxychloroquine and plasma, and casting doubt on the efficacy of masks, lockdowns, and other measures during a pandemic that has killed more than 196,000 Americans.

Much of the decline in vaccine trust has come as President Trump has also repeatedly demanded a vaccine ahead of the Nov. 3 election. Such an “October Surprise” scenario has for months roused concern among scientists who are terrified that an untested vaccine might be loosed on the public for political gain, with consequences both for curtailing the pandemic and overall trust in vaccines.

In that atmosphere, Election Day might further polarize partisan views on a vaccine, said Baum. A Biden win might deepen Republican distrust of vaccines, he suggested, while a Trump win might add to Democrats’ suspicions. “It is a very polarized country,” said Baum. The last time the US rolled out a new vaccine in response to a novel illness, the 2009 new strain of swine flu, he said, “was a ‘kumbaya moment’ compared to now.”

A contested election result that further undermines public trust in government would only make things worse for a coronavirus vaccine, Baum added. Intense disagreement over the results might lead to a patchwork of vaccine uptake, with some states having high vaccination rates while others don’t, a disaster for reopening the country.

“Vaccination and prevention are life-saving efforts that apply to everybody that shouldn't have anything to do with elections,” said former state and federal health official Howard Koh, of Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, speaking at a Wednesday briefing for reporters. “Everybody in public health is concerned about that trust and confidence being shaken.”

“The last thing we need whenever a coronavirus vaccine is approved is having people refusing to take it because they don't trust the process of approval,” Koh added.

The amount of trust in a vaccine matters greatly not just for the individual safety of people getting a shot, but for effective “herd immunity” in the public, broadly seen as requiring anywhere from 40% to 70% of the population getting vaccinated.

There are three Operation Warp Speed vaccines in late-stage clinical trials in the US. In response to questions about Trump pressuring vaccine deadlines, last week, nine pharmaceutical executives overseeing vaccine studies released a statement pledging they would abide by "high ethical standards and sound scientific principles" in requesting approval for their vaccines, a move that Offit called "unprecedented."

“We don’t even know how to measure immunity to the virus,” said infectious disease expert Stuart Ray of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, urging caution around any early reports of promising immune responses from early clinical trials. “We really need to know a vaccine is effective — it’s hard to sell something that isn’t there yet.”

The key date ahead of the election is the Oct. 22 meeting of the FDA’s independent scientific advisory committee charged with voting on the safety of vaccines. FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn has promised to seek approval of a coronavirus vaccine from the committee before releasing it on an emergency basis, although he has the legal power to ignore its views. In his remarks Wednesday, Biden called for the approval of that committee and a CDC vaccine panel charged with approving any distribution plans ahead of any vaccine release.

On the positive side, polling does suggest that Americans do trust scientists. That doesn’t mean we can ignore what politicians say about vaccines, Baum said. “In normal circumstances, political leaders are the public face of a public health response.”

“They are the people we elected to lead us, after all.”

Stephanie Lee and Matt Berman contributed reporting to this story.