The 50,000 residents of Galveston, Texas, will this month find themselves the subjects of a psychology experiment that could determine the future of supersonic airplanes.

Made famous by Europe’s sleek and ultimately failed Concorde jet, these 1,000 mph planes have in the past been stymied by their cost, environmental footprint, and perhaps most of all, their painful acoustics.

That’s because when planes go faster than the speed of sound, they create a sonic boom as intense and startling as a cannon blast, prompting the feds to ban them from US commercial flights over land. The last time a supersonic plane flew with commercial passengers was from New York to London — a trip just over three hours — in 2003.

But with renewed demand from wealthy business travelers, American engineers are itching to make quieter versions of the world’s fastest planes. Three startups — Aerion of Reno, Nevada, Spike Aerospace of Boston, and Boom of Denver — are designing planes that would cut long flights in half. Last month, General Electric announced it would create a new supersonic passenger jet engine for Aerion.

And NASA is planning to test an X-59 QueSST prototype over major US cities, suggesting Chicago as an example, in 2023. The plane will have a quieter, stretched-out sonic boom, known as a low boom, that sounds something like a car door slamming to folks on the ground.

“Hopefully they won’t hear anything,” Corey Diebler of NASA’s Low-Boom Flight Demonstrator project told BuzzFeed News in October, during wind tunnel tests of a miniature version of the X-59 at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia.

Because noise complaints could present a big hurdle to this would-be next generation of air travel, NASA is conducting the Galveston experiment as an early test of community tolerance.

Residents of the city — located on an island in the Gulf of Mexico — are used to hearing planes overhead, thanks to the nearby Scholes International Airport. But over the next three weeks or so, NASA will fly a supersonic jet (a NASA F/A-18) over Galveston, making the plane dive to create a low boom up to eight times a day. Afterward, the researchers will survey about 500 people about how much the noise bothered them.

“In some ways, building the airplane is the easy part,” Peter Coen, the leader of NASA’s civil supersonic program, told BuzzFeed News. More difficult, he said, is figuring out the best way to warn people about this new kind of noise pollution.

“We don’t want to overdo it and alarm them, but we don’t want to not tell them enough so people are surprised,” Coen said. “We don’t want people to feel like guinea pigs.”

NASA has been working on low-boom planes for decades, but was galvanized on October 5, when President Donald Trump signed a Federal Aviation Administration bill directing NASA to start consulting with the aviation industry to restart supersonic passenger travel. The Galveston thumps are a lead-in to two possible FAA rule changes: one that would establish noise standards for supersonic planes and another that would permit test flights of civilian aircraft flying faster than the speed of sound.

“We are finally, and quite literally, accelerating supersonic into the future,” wrote Samuel Hammond, of the libertarian Niskanen Center, about the new FAA direction.

Skeptics, however, doubt that people will tolerate even the quieter booms. They’re also unconvinced that travelers will pay a lot more just to shave a few hours off lengthy trips. And there are lingering concerns about fuel efficiency and emissions that doomed similar planes flown decades ago in the US, Soviet Union, England, and France.

The most famous attempt, the bent-nosed Concorde made by England and France in the 1970s, ended service in 2003 after decades of flights that rarely filled its 128 seats (at most), each passenger paying today’s equivalent of $12,700.

“Will it just be a quiet Concorde — fast but expensive?” aviation historian Janet Bednarek of the University of Dayton told BuzzFeed News by email. “Getting rid of the boom might be a first step in allowing supersonic flight over land, but generally people — especially people who move to suburbs or exurbs for the ‘quiet’ — are not very tolerant of noise.”

“I foresee great battles over where flight paths would be allowed,” she added.

The Galveston test will be a shorter, gentler version of a sonic boom experiment done five decades ago. On February 3, 1964, at 7 a.m., military jets began bombarding Oklahoma City with sonic booms. The acoustic assault went on for six months, eight times a day, preannounced at regular times. The booms grew in strength as the weeks passed, doubling in average force by July, when the government’s experiment on half a million people finally ended after 1,253 blasts.

“Bodies quivered, windows shattered, huge cracks appeared in ceilings,” noted a 2015 summary of the Oklahoma City project, organized by the FAA. “Babies cried; adults recoiled.” The booms led to more than 15,000 complaints and 10,000 damage claims, even though 70% of the population didn’t know where to direct them.

The experiment, meant to gauge the public’s acceptance of supersonic flights, found that rather than getting used to the booms, residents complained more over time. Members of the Chamber of Commerce and FAA faced death threats, and 27% of city residents surveyed said they would move rather than endure more booms.

“Oklahoma City was selected as a place supportive of the aviation industry, and people there still didn’t like sonic booms,” historian David Suisman of the University of Delaware told BuzzFeed News.

The results were a disaster for the US Supersonic Transport (SST) program, a 1960s bid to build a supersonic jetliner, changing sonic booms from a minor annoyance to the central objection to supersonic travel. The FAA concluded that the public would accept quieter booms, like the ones deployed at the very beginning of the experiment, but a National Academy of Sciences panel soon concluded the opposite, warning they might cause car accidents, heart attacks, lost sleep, or people falling off ladders.

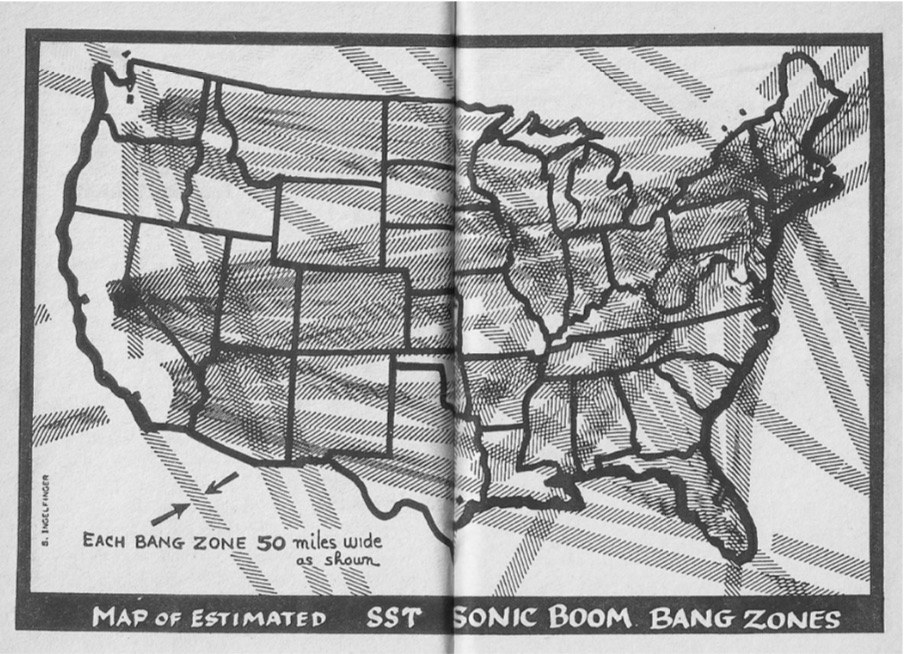

A sonic boom is not a sound wave, but a shock wave, an outburst of compressed energy created by an object traveling ahead of the sound waves it creates. (People inside the plane don’t hear the boom as they are literally out-flying it.) Shocks off the leading edges of a plane combine and trail behind it in a cone-shaped “carpet” about 50 miles wide. Rather than building up like the sounds of an oncoming jet, all of that sound energy is delivered at once in a startling boom.

“Anywhere there’s a bump that comes off the aircraft it’s going to create a shockwave,” Diebler of NASA said. What happens normally on a supersonic aircraft is all those little waves coalesce to lay down on the ground together at once, “so it sounds like a cannon going off,” he said.

After the Oklahoma City tests, environmental groups — such as the Citizens League Against the Sonic Boom (CLASB) and the Coalition Against the SST — sprung up to complain about the booms. This criticism fed into a broader environmental movement campaigning against noise pollution in cities.

In the late 1960s, for example, a new group called Friends of the Earth took up the supersonic boom as its primary cause, forming a coalition with both environment- and cost-conscious senators opposed to the SST.

“In those days, the staffers of both parties were young people worried about the environment, and over time they convinced their bosses to oppose it,” Charles Shurcliff, whose father, William, founded CLASB, told BuzzFeed News. William made a nationwide map of supersonic “bang zones” that was particularly effective at rousing opposition.

SST supporters, meanwhile, made arguments for the plane based on economic and national prestige, calling sonic booms “The Sound of Security” and arguing that mild ones posed little threat of damaging homes. The US Air Force even tested whether sonic booms could crack eggs in chicken coops or stop minks and turkeys from reproducing. (“Even under the most extraordinary circumstances, sonic booms from practical aircraft maneuvers do not pose a threat to avian eggs,” concludes one NASA report.)

No matter. The death knell for the SST and supersonic travel in the US came in by a then-rare filibuster in the US Senate (all the more unusual today for being bipartisan), that ended at 9 p.m. on New Year’s Eve of 1970.

In 1973, the FAA banned passenger airlines from supersonic flights over the US. The decision was a landmark — and largely forgotten — victory for the early environmental movement, making “noise pollution” a real issue for airplane designers to contend with thereafter. It also knocked out 80% of the market for supersonic flights, according to a 1998 analysis by the late aviation economist R.E.G. Davies, which helped kill off the industry’s appetite for the Concorde.

The first rules about noise levels, instituted in the 1970s, limited planes to roughly 100 decibels overhead. The FAA’s current standard for noise is 65 decibels, averaged over a 24-hour period, long controversial among homeowners on flight paths, who have to listen to take-offs and landings as they happen, not spread out over a day. (In 2015, the agency said it was starting a study to reexamine this standard, with its release scheduled for 2017. It still hasn’t been released, and the agency did not reply to a request for a release date from BuzzFeed News.)

The rules only apply to subsonic flights. Newer rules instituted in the 1990s meant that newer planes like the Boeing 737 were about 10 decibels quieter than older planes flying overhead. Tightening of these rules has meant that instead of 7 million people “exposed to what is considered significant aircraft noise,” in 1975, today only about 314,000 are, according to the FAA. New 2018 rules call for another 7-decibel drop for future flights.

But for new supersonic models, like NASA’s X-59, “Any noise is an issue,” aviation historian Bednarek said. Even as aircraft have become quieter, noise complaints have continued, she noted. “In fact, one could argue that making aircraft quieter just lowered the threshold at which people would start to complain.”

NASA's Corey Diebler and team test an X-59 model in a wind tunnel with smoke and lasers.

Lockheed Martin will build the X-59 in 2019, using a number of engineering tricks to spread out the shock waves and create a softer boom.

The main change is its pencil-like length and shape, which stretches out the distance between the nose and wing shocks. To allow for its pointy nose, the cockpit will lack a front window, instead relying on a camera for the down-slanted view of the runway over its long, pointy nose.

The jet also uses small fixed wings just behind the cockpit and “thump bumps” under its tail that will change the shape and direction of the supersonic shock waves coming off the aircraft’s back end in a way that spreads them out instead of letting them join up with the shocks coming off the front of the plane. The combination of wings, bumps, and length optimized for that speed, around 940 mph at an altitude of 55,000 feet (the cruising range of the plane), should deliver a sound “like distant thunder,” said NASA’s Diebler. “You might still hear a thud, but it shouldn’t be a sharp, intense noise.”

When built, the X-59’s sonic carpet will be only 15 to 20 miles wide instead of the 50 miles of the SST. But because a sonic boom travels behind an aircraft, the thump would not only hit people near the airport but would follow the entire flight path of the aircraft while it is supersonic.

“So the number of people subjected to this ‘thud’ or ‘thump’ would be much larger than those subjected to noise now in the vicinity of airports,” said Bednarek, the University of Dayton historian. “More people — more potential complainers.”

And the noise would happen in places where people are not accustomed to hearing any aircraft at all, she added.

NASA is building the X-59 to eventually spur commercial development of a 50- to 80-seat business jet, about the size of what Aerion, Spike, and Boom are proposing (though none of the three startups have yet built a prototype).

But sonic booms alone didn’t kill the SST and Concorde, business professor Mel Horwitch, author of Clipped Wings: The American SST Conflict, told BuzzFeed News. Rather, it was a combination of economic and environmental objections that actually killed the plane: The $260 million cost of the government program in 1970 alone was too much for US lawmakers.

In the aftermath of the SST’s demise, seen as a blow to US technological prowess, Boeing went on to make a killing on the subsonic 747, which could carry hundreds of passengers. Meanwhile, England and France squandered $2.3 billion on the Concorde, seen as a “commercial disaster” as early as 1977 when it carried only 70 passengers and cost three times as much as its subsonic competitors.

Those same economic problems may dog the new supersonic jets. Proponents point to market projections claiming hundreds of supersonic business jet sales in the decade after an overland flight ban is rescinded. Similar optimism accompanied the SST and the Concorde, however, which in the end supported a fleet of 20 planes.

Aerion touts flights from New York to Shanghai and Brisbane, but supersonic flights across the Pacific are pointless for business travelers, Davies noted in his 1998 analysis. The 12-hour difference in trans-Pacific time zones means business travelers from America and Europe would arrive in Asia either as their hosts are asleep or they themselves are ready to pass out. Better a subsonic flight and a night of sleep than trying to negotiate in Beijing at what feels like 1 a.m., he argued. (Aerion declined to answer questions about its business model from BuzzFeed News.)

Newer passenger jets have actually gotten a bit slower in recent decades, as the price of fuel has risen and airlines chased efficiency and cleaner emissions. All of the startups aiming to fly supersonic in the next decade have touted low emissions as a goal, but it simply takes more fuel to go faster, raising critical questions: An analysis by the International Council on Clean Transportation suggests the proposed supersonic business jets would emit 40% more nitrous oxide and 70% more carbon dioxide, the primary greenhouse gas driving global warming, than subsonic ones. That’s because they burn about five to seven times as much fuel per passenger, compared to subsonic flights.

Boom is looking at creating a 55-passenger plane, aiming at business travelers (which account for only about 5.3% of all non–economy class air travelers, according to the International Air Transport Association).

But Aerion and Spike are hoping to attract mega-wealthy flyers, with proposed 8- to 12-seat and 18-seat designs, respectively. The notion of plutocrats traveling at supersonic speeds overhead while the 99% travel slower might chafe, but from an environmental standpoint, that might be better, Suisman, of the University of Delaware, said. “A few business jets are going to release a lot fewer emissions than fleets of large supersonic passengers planes,” he said.

And 2023, when the X-59 is scheduled for flight tests over US cities and the FAA aims to reexamine its supersonic ban, might be a very different environment for worries about the effect of airplane emissions on the climate, compared to today’s FAA run by the climate-heedless Trump administration.

“I do wonder if this is technology that we will want in the next few years, with concerns about climate change and each person’s carbon footprint becoming more prominent,” Horwitch said. He was calling Washington, DC, from Budapest on FaceTime to make that comment, he noted, and the internet is only going to get better at making such connections in five years. ●

CORRECTION

A NASA F/A-18 will fly in the Galveston experiment. An earlier version of this post said the plane belonged to the Air Force.