On his first trip to Alaska, while hiking the trail to Exit Glacier, helicoptering over Kenai Fjords National Park, and boating through Resurrection Bay, President Obama focused his public remarks — and Instagram selfies — on the threat of climate change.

Alaska is one of the best places to see the consequences of our warming planet: thinning sea ice, melting permafrost, and retreating glaciers. Temperatures have risen there about twice as fast as the rest of the country over the last 60 years, extending the wildfire season by a month and melting 75 billion tons of glacial ice every year.

"We're here today," Obama said in remarks at the Conference on Global Leadership in the Arctic last week, "to discuss a challenge that will define the contours of this century more dramatically than any other — and that's the urgent and growing threat of a changing climate."

"Let me give you a shot of what we're looking at all across this incredible valley." —@POTUS: http://t.co/Bj2OH3qUJM

But Obama's calls for climate cooperation carry an inherent contradiction. To curb global temperatures, we need to stop burning fossil fuels. And yet, the U.S. is in a competition with Russia, Norway, and other nations for the Arctic's rich resources, notably oil and natural gas. It's a battle that's been going on for centuries — and one that has ironically birthed much of modern climate science. First delayed after the 2008 recession, Arctic oil exploration looks stymied, for now, by precipitous drops in oil prices. But the political battle over the region grinds on.

"The United States is, of course, an Arctic nation," Obama said in his remarks, reminding visiting dignitaries that the U.S. chairs the Arctic Council, the eight-nation body with interests in the polar region, which will have a big voice in both environmental and energy decisions in the Arctic. "We are not going to — any of us — be able to solve these challenges by ourselves. We can only solve them together."

Ever since 1867, when the cash-strapped Russian czar sold Alaska to the U.S. for $7.2 million, Russia has regretted it.

Five years after the sale, Americans discovered gold there, and a few decades after that, oil.

The U.S established a 22-million-acre National Petroleum Reserve near Prudhoe Bay in 1923. Discovery of massive, and lucrative, oil reserves there in the late 1960s, which kicked off an Alaskan oil rush, is fresh in the memories of the nations now carving up a warming Arctic like teenagers eyeing a hot pizza.

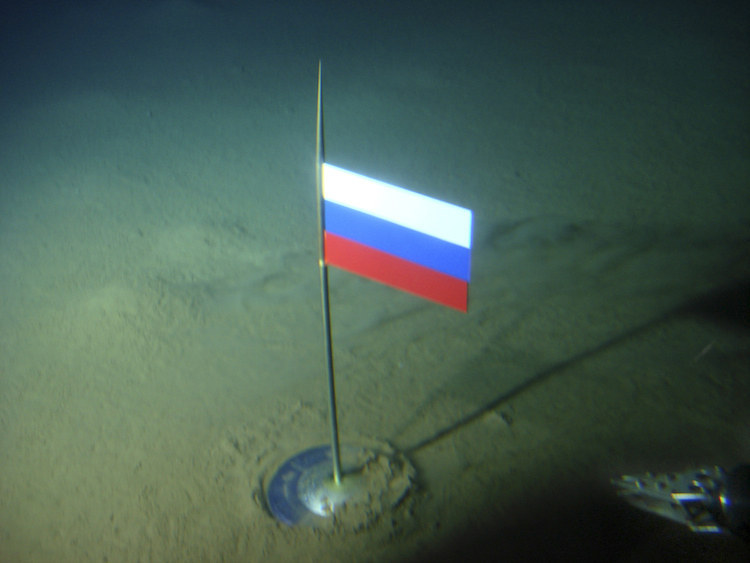

Jockeying to exploit the Arctic has intensified since 2007, when a Russian submarine planted a titanium flag on the seafloor under the North Pole. A $27 Russian billion project aims to tap the Shtokman field, one of the world's largest natural gas fields, just offshore of the Kola peninsula. Denmark, Canada, and Russia have all filed claims on the Lomonosov Ridge, a 1,100-mile-long underwater mountain chain that runs beneath the North Pole.

What's more, melting summer sea ice, though terrible for the environment, has opened shipping lanes that 19th-century explorers died searching for. As a result, the U.S. and Russia have started exploring drilling in the Arctic Sea, where 90 billion barrels of oil are estimated to lie in reserve.

Russia started operations on the world's first ice-resistant oil rig in 2013, the Prirazlomnaya platform in the East Barents Sea. Greenpeace sent its own ship to protest the rig, which Russia then seized, detaining activists for two months. In May, Obama gave Shell permission to drill six exploratory oil wells off Alaska's northern shore, drawing complaints from Greenpeace and other environmental groups.

Some say that concerns about Arctic oil leading to increased global warming are overblown because the stuff will be so expensive to drill. David Victor, an international relations expert at the University of California, San Diego, told BuzzFeed News that the real Arctic environmental worries are oil spills and similar disasters.

Technically, control of Arctic territory — which is under ice much of the year — is governed by a treaty called the U.N. Convention of the Law and of the Sea. In August, Russia used the treaty to claim 460,000 square miles of territory under the Arctic Ocean, extending right up to the North Pole. Denmark has claimed some 346,000 square miles as well.

The U.S. can't grab pieces of the Arctic under the treaty, because it isn't a part of the U.N. Convention. The Obama administration supports signing on, just as the previous Bush administration did, but it's unlikely to happen. That's because Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell opposes the treaty, along with enough of his colleagues to block its passage.

Without the Convention, the U.S. uses another strategy to claim territory: with giant ships, called icebreakers, that mark national sovereignty by opening sea lanes. Last week, Obama called for the U.S. to buy more icebreakers. The U.S. Navy and Coast Guard only have a handful of aging ships, and just two of them are fully functional. In contrast, Russia has 40 icebreakers, with reported plans to buy 11 more. China, meanwhile, sent its own icebreaker to the Arctic in 2012, and last week startled observers by sending a naval task force offshore of Alaska during Obama's visit.

In another territory-marking move, Obama called Wednesday for the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA), the nation's spy satellite mapping agency, to produce the high-resolution topographic maps of Alaska. The maps will also track the effects of melting permafrost, retreating glaciers (one of which he visited on his trip) and wildfires.

A gold-rush mentality over Arctic territory has played out for centuries, historian Michael Robinson, author of The Coldest Crucible: Arctic Exploration and American Culture, told BuzzFeed News, with chilled sailors planting frozen flags everywhere as markers of ambition on the world stage.

"Because the Arctic has so many identities — native homeland, endangered habitat, font of resources — it lends itself to all kinds of geopolitical theater," Robinson said.

In the 19th century, explorers from imperial powers in mercantile competition sought to plant those flags on the North Pole and to open a "Northwest Passage" across Canada to the Orient. A century later, with a new set of superpowers, the Arctic was a battlefield of the Cold War, Robinson said. "The issues are different, but many of the story lines remain the same."

Climate science owes a heavy debt to the Cold War, when the U.S. and Soviet Union faced off across the North Pole.

In the 1950s and 60s, U.S. military bases in Greenland and Alaska launched a host of important scientific research efforts, such as taking precise measurements of Arctic temperatures and melting sea ice. Glaciology, the study of ice and its environmental impact, was barely a discipline until the U.S. Army found itself fearing invasion across polar ice.

Back then, understanding the Arctic mattered because the major weapons of the era — bombers, intercontinental ballistic missiles, and nuclear submarines — would cross its frontiers.

"With the Arctic viewed as the likely staging ground for the third World War, understanding the Arctic, including evidence of rapid warming that had begun earlier in the 20th century, was a national security issue," Ron Doel, a historian at Florida State University, told BuzzFeed News.

The discovery that Greenland's ice warped and shifted rapidly, a key to understanding the potential collapse of glaciers today, was partly made as a result of efforts to build a nuclear-powered ice fort there in the 1960s. The U.S. abandoned its ice tunnel base there, called "Camp Century," in 1965, as Cold War tensions thawed.

Greenland's ice records and temperature measurements lasted, however, and kick-started climate science's efforts to understand how global warming affects the poles. In the early 1970s, ice cores drilled at Camp Century revealed that past Ice Ages had ended swiftly, pointing to sudden climate change happening in the past, and warning of its possibility in the present.

Russia has long viewed the Arctic as its destined frontier, much as the American West once captured the U.S. spirit with talk of Manifest Destiny.

"I would say the Arctic is not just an interest of Russia, but an essential part of the national character," Sergei Medvedev, a political scientist at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow, told BuzzFeed News.

Beginning in the 1600s, Russian and Northern European explorers sailed north, looking for a fabled ice-free sea believed to cover the North Pole. Their search culminated in the craze for polar expeditions at the end of the 19th century.

Over the past three decades, summer sea ice cover has declined about 30% in the Arctic, bringing a version of this vision closer to reality; some projections see the summer Arctic losing all of its ice by the 2030s.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the Soviet regime mounted heroic explorations along Russia's northern edges, aiming to establish a Northeast passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific, Russian historian John McCannon of Southern New Hampshire University in Manchester told BuzzFeed News. These adventures were celebrated in films that made Arctic exploration, exploitation, and sovereignty everyday ideology for many Russians.

The Soviet Union actively planted outposts along Russia's northern coast in a bid to build the infrastructure for this sea lane, and jousted with Canada and the U.S. over possession of Wrangel Island and other Arctic shipping outposts in the 1920s. "The size of Russia's icebreaker fleet is a reflection of this longstanding interest in the Arctic," McCannon said. "Not all of them work, or are the very large ones. Nevertheless, they are there."

Russia's 2007 undersea flag planting near the north pole was actually in part a 50th-anniversary homage to a 1937 Soviet polar expedition, McCannon added. "The bottom line is that Russia has a stubborn feeling of possession of the Arctic that is foreign to the U.S."

Although Obama has spent most of his trip to Alaska talking about climate change there, on the list of Arctic priorities for the intensely nationalistic regime of Vladimir Putin, Medvedev said, "climate comes last."

Underneath the political rivalries, he added, the Arctic is a crazy place to compete because survival is so hard and oil is so cheap right now. The high risk of disasters and accidents mean that would-be competitors always end up having to help each other out. The six Arctic indigenous groups, including Alaskan and Russian natives represented on the Arctic Council, also aren't overly concerned with national border boundaries, either.

"The Arctic is a victim of geopolitical delusions," Medvedev said, saying the gold rush to the region seems unprofitable now in an era of falling oil prices. "Half-jokingly, in Russia there are always comments and claims about someday getting Alaska back."