The Chinook helicopters lifted off, and Richard Hunter’s mind was at ease.

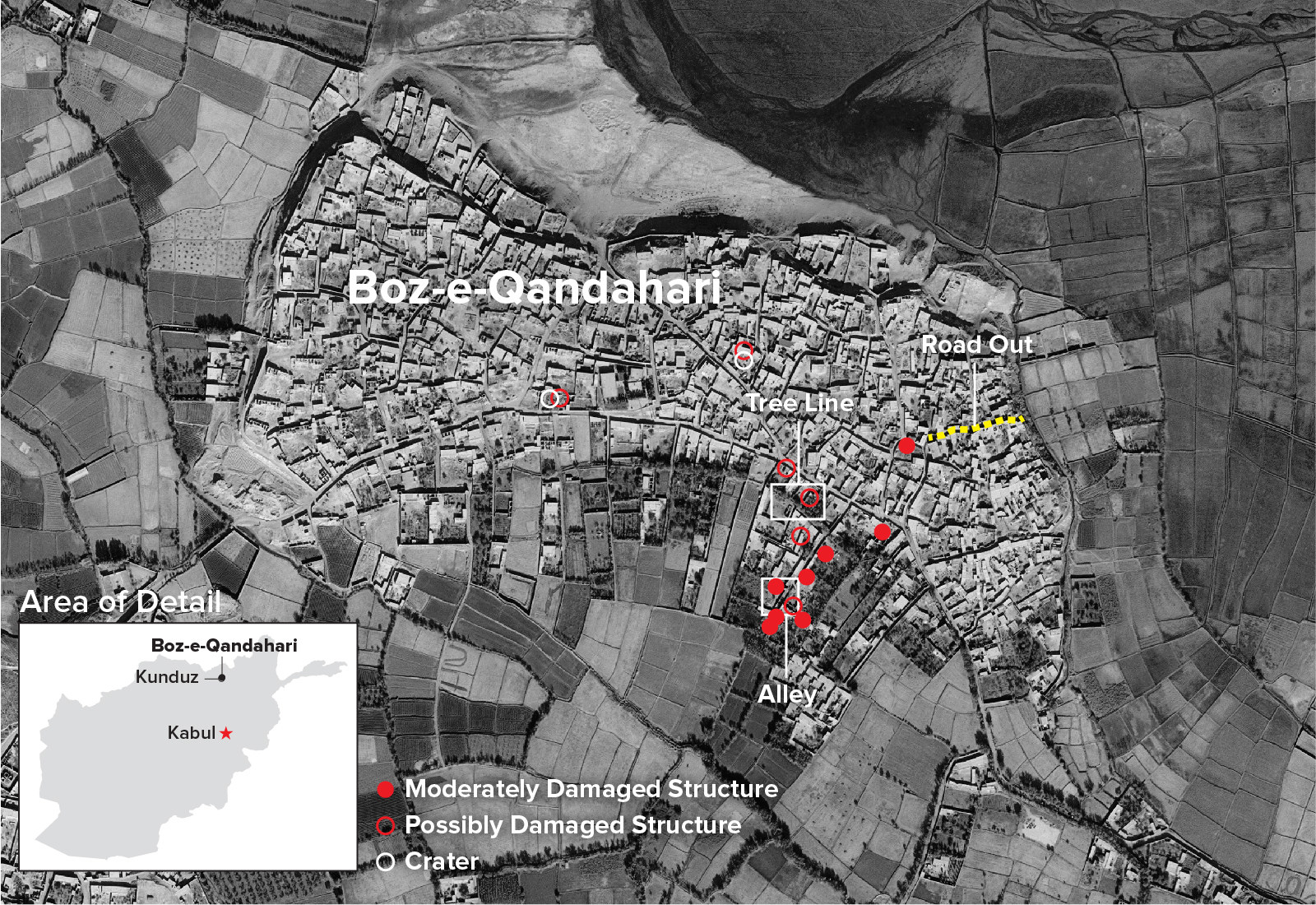

It was Nov. 2, 2016, and he was strapped into one of two mammoth CH-47’s flying over the city of Kunduz in northern Afghanistan on a moonless night. Loaded with 59 men in all — a company of Afghan commandos and a team of Green Berets backing them up – the big birds were headed to a village called Boz-e-Qandahari on Kunduz’s northern outskirts.

He and the rest of the men had no idea that they were flying into a deathtrap — one that, thanks to incomplete intelligence, would claim the lives of two Green Berets, three Afghan commandos, and 32 civilians, including six women and 20 children. The civilians died as the American and Afghan raiders faced an unanticipated onslaught of Taliban fighters reminiscent of the Mogadishu slaughter memorialized in the movie Black Hawk Down.

For their actions that day, three of the Green Berets would receive the nation’s third-highest award for valor, the Silver Star, one of them posthumously, and Hunter was honored Oct. 17 with the Air Force’s second-highest honor, the Air Force Cross, along with five men on the gunship above them who will receive Distinguished Flying Cross medals.

The citations for those awards make no mention of the errors that forced the fighters to act so heroically or the civilian deaths that led a United Nations humanitarian organization to call for an international investigation.

Such carnage is likely to happen again as the Trump administration adds as many as 3,000 troops to the US contingent in Afghanistan. The top US commander there, Gen. John Nicholson Jr., promised recently that “a tidal wave of air power is on the horizon” against the Taliban.

Hunter, a US Air Force staff sergeant, was the combat controller for the Special Forces mission, responsible for relaying overhead reconnaissance to the team on the ground and directing any needed airstrikes. During the mission, Hunter would call down the closest-range airburst round ever fired near friendly forces from an AC-130 — a gunship that has been in service since Vietnam.

The Green Beret unit was known as ODA 0224, short for Operational Detachment Alpha, the fourth team from the second company of the second battalion of the 10th Special Forces Group based at Fort Carson, Colorado. They were the fighters on the shadowy front lines of the unconventional war in Afghanistan, the longest-running conflict in US history. This was their sixth capture-kill mission in Afghanistan.

Hunter, then 25, knew every one of the Americans on the two helicopters. He’d fought and trained with them, and had joined the team at the personal invitation of its leader, US Army Captain Andrew Byers, a 30-year-old West Point graduate.

At the start of the mission, Hunter had checked in with the AC-130 gunship aircrew flying in circles over Boz-e-Qandahari, a muddle of walled compounds perched on a bluff above the Khanabad River. The gunship reported nothing unusual.

"Everything went wrong.”

The men leaned forward in the bench seats as they neared the village. Their mission was to kill or capture a Taliban leader reportedly named Qari Mutaqi who US officials suspected was plotting an armed assault on Kunduz, the third Taliban effort to take the provincial capital in a year. He was thought to be living in two walled courtyard homes at the end of a long alley. The troops had spent two weeks planning his capture.

“Everything went wrong,” Hunter would say later. “The only thing that went right was we found the helicopter landing zone.”

“It was a pretty simple mission,” said Army Sgt. 1st Class Brian Seidl, the US “team sergeant” for ODA 0224, the man in charge of tactics on the mission, assigning who kicked in what door, who shot at whom, who did what. “It was not a training mission — we were partnering with the Afghan force.”

The team’s helicopters landed, as intended, in a field about a mile from the village. It was a dark, partly cloudy night with temperatures in the 60s. The landing zone was actually closer to a different village, a ruse intended to confuse the Taliban in Boz-e-Qandahari about the purpose behind the noisy arrival of the helicopters.

But instead of the dry field they expected, the troops found themselves jumping into waist-high water; their landing zone had been flooded for rice season.

The Chinooks settled into the muck. A few potshots rang out in the darkness from the closer village as the men jumped out, sporadic fire aimed at the helicopters in the rice field, and then the machines lifted off and flew away.

High overhead and miles away, the gunship crew watched as the troops slogged through the mud. It would take an hour to traverse the flooded field, the first setback in a mission meant to last only a few hours.

The crew, with the radio call sign "Spooky 43" aboard the AC-130, saw something else surprising as they watched the troops advance — the blurry forms of a few people still awake in the village, unusual for midnight. Air Force Maj. Aaron Hall, the fire control officer aboard the AC 130, recalled another unwelcome sight.

“I see a couple dudes on this rooftop-type area, and what appeared to be some guns up against the wall.”

Any hope of surprise was gone. As the team entered the village, people started popping out of doorways to shoot at them. So did the pair on the rooftop. The troops took cover, and Hunter radioed the airplane overhead.

“The conversation is pretty simple,” said Hunter. “We’re being shot at. Just make it … stop.”

Two AH-64 Apache helicopters that were accompanying the mission, equipped with laser-guided Hellfire missiles, rockets, and a machine gun loaded with 1,200 rounds of high-explosive ammunition, quickly killed the shooters.

But with that, “the jig was up and we needed to get moving,” Hunter remembered.

As the team went about its mission, Hunter imagined a map extending hundreds of yards around him and miles above, marking his friends, allies, aircraft, and the people trying to kill him. A combat controller plays a kind of three-dimensional chess in his head while everyone else around him is fighting, stacking up the aircraft in flight like an airport control tower operator to call in airstrikes in the middle of a firefight.

“Not everyone is cut out for this,” said Col. Michael Martin, who commands the US Air Force’s 24th Special Operations Wing, which trains and deploys the combat controllers on special operations missions.

“I tell them you do not want to be the weakest link. You do not want to be the guy who holds up the team.”

Special operations teams “can’t stay in any one place for too long. That makes us vulnerable,” said Seidl.

The Americans moved quietly, equipment strapped to their sides to reduce noise, the Afghans less so. They picked their way through a maze of streets lined with mud brick walls that surrounded enclosed courtyards. It was quiet and dark. There were no streetlights.

Mutaqi’s compounds were at the end of a long north-to-south-running alley, lined by 10-foot-high courtyard walls. The Afghan commandos were in front (“It’s their country,” Seidl said) at the south end, with team leader Byers, Hunter, and Seidl initially about midway up the alley. A rearguard flanked the alley’s north entrance.

Reconnaissance flights had shown the entrance to the compound as wide open, but that turned out to be the case only during the day. When the raiders arrived, they found the entry blocked by a 20-foot-tall steel gate. During the day, its opened doors had been tight against the wall and hidden by trees; at night, it was a formidable obstacle.

High above, the aircraft crew could see two individuals on the other side, perhaps armed (night sensors can make out shapes, but they are not precise enough to tell an AK-47 from, say, a club). “They looked like they were up to no good,” said Hall, who watched them running back and forth behind the gate, and called down to the team.

“That was the conversation we were in the process of having when all hell broke loose,” said Hunter.

“A dude comes running out, pauses for a second, his arm comes down and then he goes like this,” Hall said, miming a lob, “throwing a grenade, but there was just zero time — it was so fast.”

The blast wounded two Green Berets, Sgt. 1st Class Ryan Gloyer, an intelligence specialist, and Sgt. 1st Class Sean Morrison, the medic, as well as many of the Afghan commandos bunched in front of the gate.

Hunter, 30 feet away, felt the grenade’s heat. “A particular four-letter word came to my mind,” he said. Everyone ran to the wounded and grabbed them, trying to bring them back and give them some cover. Then they started firing back at the people who were suddenly shooting at them from all over.

“We were expecting a pretty normal capture-kill mission. And we walked into a hornet’s nest,” said Hunter.

"We walked into a hornet’s nest."

High overhead in the AC-130 gunship, Hall watched the alleyway light up. “We knew it was bad,” he said. “What we weren’t clear on, at first, was how bad it was. Were all those guys killed with that grenade?”

As soon as they heard Hunter’s voice giving them permission, the AC-130 started to fire its 40mm cannon at the south side of the gate. They used the smaller cannon because Hunter and the wounded were then only about 60 feet up the alley. This was blisteringly close. On typical missions, the team engaged targets that were hundreds or thousands of yards from friendly forces.

Meanwhile, people were firing from second-story windows from most compounds along the alley, said Hall. “Those guys probably had eyes on them the whole time, and were just waiting for them get down into that death funnel.”

“I would describe [the incoming fire] as coming from everywhere — in front of us, behind us, from above us. I would even try to tell you it was coming from below us,” Hunter said. Within the first minute, the team sustained 16 casualties and started dragging the wounded back toward the center of the alley.

As they retreated, Hunter called for a curtain of airstrikes along the alleyway, with fire coming from both the airplane and the attack helicopters. Since the shooting was coming from inside houses, the AC-130 fired high-explosive rounds from its howitzer with the fuses delayed to go off inside those structures, so they would kill the person shooting at the team.

One of the first targets on the walk back was one of the reputed Taliban compounds at the end of the alley, southeast of the one with the steel gate. Rifle shots were coming from a second-story window there. After a few airstrikes, the compound suddenly erupted with a tremendous secondary explosion, lighting up the sky and filling the air with dust, smoke, and debris.

From the air, Hall saw “a massive fire” that briefly illuminated the entire village. The airstrike had hit a munitions dump.

Then at the north end of the alley, the rearguard began taking fire. A team assistant leader was shot five times. Another Green Beret grabbed the wounded man by the chest plate of his body armor and dragged him from the mouth of the alley while shooting back at the attackers and applying tourniquets to both of the wounded man’s legs.

Now the team was retreating from both ends of the alley to its center. The fire from the gunship grew so intense that its biggest gun, the 105mm howitzer, overheated, and the crew had to load it manually. Normally an automatic loader puts a shell into the gun’s breech, where it waits until the fire control officer — Hall — orders it fired. But letting the shell sit in an overheated barrel would cause it to detonate inside the plane, killing everyone aboard. Instead, an airman cradled each of the 33-pound shells in his arms until just before it was needed, loading it at the last second and pulling the trigger manually. It’s a procedure the aircrew practices, but hopes never to resort to.

And it was about to get worse for the retreating team on the ground. The Spooky 43 crew could see the entire village, drawn by the noise, converging on the alley, like an anthill stirred up by a child’s stick. Forms carrying rifles could be seen running along lines of trees toward the scene to bottle up the mission. “They just kept coming, kept coming,” Hall said.

No one had suspected the village sheltered that many Taliban fighters, another intelligence failure.

Fearing being trapped at both ends of the alley, Byers decided to break out to the side. He kicked a door in one compound’s 10-foot wall and reached to push it open, when someone on the other side opened up with an automatic weapon through the door right into him.

As he fell, both Seidl and Hunter emptied their weapons at the door at whoever had fired, and pulled the wounded Byers from the doorway.

Now Seidl was in charge. With roughly a third of the mission team wounded and no hope of escape down the alley, he ordered his team into a compound on the other side of the alley. This one had a wall only 5 feet tall, a disadvantage that meant people could shoot down into the yard more easily. But it also meant the team could see over the wall to observe that it was clear.

At this point, they were boxed in. Seidl was now in charge of a medical evacuation as well as a firefight.

“We can’t do our jobs standing in the alley getting shot,” Seidl would say later of this moment. “Dick [Sgt. Hunter] can’t think. I can’t think in that situation. We needed to take cover.”

With few men unwounded, the job of clearing the compound fell to Seidl and another Green Beret, followed by Hunter. “It’s not ideal to have your command elements clearing a compound, but we had a lot of casualties and we needed to get everyone in there,” said Seidl.

“This is what I would call an apocalypse.”

On the radio, one of the Apache helicopters told Hunter they had “Winchestered,” meaning they had run out of ammunition, and were returning to base to pick up more in the middle of the firefight. That doesn’t happen very often and certainly wasn’t the plan.

The Americans and Afghans hustled into the compound, cleared out a small house, and set up a perimeter around the yard. Instead of the few hours planned, a long night was ahead. Gunfire and grenades were coming from every direction, and Taliban members were headed their way from all over the village.

“There is a point over our training for where we all deal with what's called the apocalypse scenario,” where there are no good options and a team is down in numbers and surrounded, said Hunter. “This is what I would call an apocalypse.”

No sooner had Hunter sat down in the refuge compound with his back to a wall when he heard voices coming from the alley they had just left, yelling through the din of gunfire for help. They were American voices.

The Afghan commandos watching over the wounded Green Berets had fled into the refuge compound’s courtyard with everyone else, leaving the assistant team leader who was shot five times still out in the alley along with another wounded American, the medic.

“I didn’t even think,” Hunter said, putting his arms out like wings to re-create the moment. “So I just grab the two nearest bodies to me, which happen to be two US Special Forces members, and tell them, 'Hey, come with me,’ and ran out of the alleyway and [said] ‘Let's get our brothers.'”

The alley was filled with smoke and reverberating with bullets ricocheting all around them. “It’s loud. It's pretty much the scariest thing imaginable,” said Hunter. The darkness was almost complete, with visibility only 5 feet as they ran down the alley, looking for the wounded.

The men moved as fast as they could. The fire was so intense that the rounds were skipping off the ground, off their feet, hitting around the walls next to them. “It was a miracle that nobody else was hurt."

They found the wounded men in the darkness, and set off hauling them back to the sanctuary compound. All the while, Hunter directed airstrikes with a radio in one hand while dragging a man 30 yards up the alley to the secure compound with his other one.

Inside the compound, the Green Berets stationed unwounded Afghan commandos around the perimeter of the courtyard. Despite medical attention, Gloyer, the Green Beret hurt worst in the initial grenade attack, died as the Taliban closed in on the compound.

“He was the one I could always count on,” said Seidl, the team sergeant.

High above, the AC-130’s gun crew was hard at it, cradling shells and working the cannons on an airplane twisting to aim at targets. The plane’s 40mm cannon malfunctioned five times during the fight.

“We’re trying to help target these positions where people are just raining fire down on these guys,” Hall said.

During the siege, Hunter and Seidl kept 20 feet apart by unspoken agreement. To lose both of them from a single grenade or gunfire burst in the middle of the fight would have been disastrous for the mission. Instead, they communicated by radio across the short distance, with Seidl signing off on airstrike requests by radio. They did this for the next hour and 47 minutes.

In that time, the mission set a record for "danger-close" airstrikes, technically ones in which there is at least a 1 in 1,000 chance of hitting their own troops. But in reality the odds were much higher fighting in an alleyway. Hunter called in 31 that night, 19 of them from the gunship.

Each missile or shell aboard the Apaches and AC-130 has its own danger-close range. The gunship’s 105mm howitzer high-explosive rounds have a danger-close range of several hundred yards, for example. The smallest rockets on the Apaches have a danger-close range of about 200 yards. Hunter’s closest strike from one of those rockets was called in for 9 feet away from him — aimed at attackers just on the other side of the compound wall.

“That’s not the preferred method for dealing with gunfights,” Hunter said. “This was very in your face.”

The Spooky 43 crew fired so many high-explosive howitzer shells that night that it ran out, leaving only airburst shells in its armory. But rifle fire and hand grenades were coming from right across the alley, the compound that Byers had initially sought to take refuge in. “Fighters were flowing in from that position. We had to keep targeting it,” Hall said.

Stopping that fire meant shooting an airburst shell. The 33-pound, unguided projectile — intended to explode far above masses of enemy infantry — would have to be blasted from a moving aircraft to reach a house in an alleyway more than 2 miles away, the shot buffeted by winds the whole way.

Lying flat on his stomach, Hunter called in the airstrike after Seidl gave his approval.

"If white had a taste, that was it."

The aircrew fired the shell and waited a long seven seconds for it to travel from the AC-130 to the compound across the alley. “I’m not sure anybody breathed,” said Hall, who had made the wind adjustments for the shot.

When it arrived, the explosion was tremendous.

“Very violent. Very loud. Very bright,” Hunter said. “It tasted like if white had a taste, that was it.”

The airburst flung him into the air, and on his way down, the shock wave lifted the ground below to meet him, punching along the length of his body. The blow clicked the talk button on his chest radio handset, delivering the roar back to the aircrew.

“It overpowered all the other noises going on at the time,” said Hall.

There were about 10 seconds of silence. “Was that you?” asked Hunter of the gunship.

“Yeah.”

“How close was that?”

“Around 15 meters.”

“Okay. Nice shot.”

Hunter requested that they keep the next one at least 75 meters away.

(“I was pretty stupid after that, for about 30 seconds,” Hunter said. “I was ready to puke, that kind of stuff. It was not cool. But also, neat.”)

After that, nothing came from the compound across the alley for a long while.

Relying on airstrikes to protect a hunkered-down special operations team is not a new thing, said Col. Martin, the 24th Special Operations Wing commander.

In the 1993 Battle of Mogadishu made famous by the movie Black Hawk Down, he noted, an Air Force combat controller, Jeff Bray, kept US Army Rangers and Delta Force soldiers from being overrun by calling in airstrikes all night long.

Black Hawk Down also started with a mission to capture leaders of an insurgency, lieutenants of the Habr Gidr clan led by a warlord named Mohamed Farrah Aidid. The battle killed 19 Americans and more than 300 Somali militia and civilians, according to a UN estimate.

Attacks on the leadership of insurgencies have been a staple of US military practice at least since 1901, when an insurrection in the Philippines ended with the capture of rebel leader Emilio Aguinaldo. In Afghanistan, the US has eliminated a series of Taliban leaders, most notably the head of the Afghan Taliban, Mullah Akhtar Mohammad Mansour, killed with a drone strike in 2016. And of course there was the death of Osama bin Laden in 2011.

ODA 0224’s mission, and past ones, followed in that tradition.

With dawn only hours away, the trapped men needed to escape Boz-e-Qandahari, or lose the advantage of night vision. “Definitely it was a worst-case scenario, with almost a third of the force wounded,” Seidl said. They had to get out of the village.

The AC-130 overhead was joined by another gunship for Hunter to manage, another rarity: Two gunships are also not regularly stacked together on these missions.

After almost two hours, a relief force of 10 more Special Forces soldiers reached them from Kunduz. They decided to break out back along another alleyway and the main road out of town.

“We had to carry all our dead and wounded,” Hunter said. “Everybody was carrying somebody.” Byers was carried on a stretcher.

Hunter was reminded of his training, during which instructors had relentlessly made students lug heavy, unwieldy stones everywhere, as he called in airstrikes on the new shooters while firing back at them himself, all while sweating under his heavy armor and equipment. “You’ve got a dead guy on your back,” Hunter said. “It was one of the hardest things I’ve ever done.”

It was a running gunfight, one that lasted another 40 minutes, with shooters steadily popping up to fire at them as they went. The Spooky 43 would “paint” the windows where the gunfire originated with its 40mm gun, and the Apaches would fire Hellfire missiles into them to kill the people inside.

On the way out, a gunship also blew up a “technical” truck spotted in the village with some kind of weapons mount in it, another surprise that intelligence had missed beforehand.

Dawn broke. With so many wounded, Seidl called for a medevac helicopter to land some 400 yards outside the village, even though the mission was still taking fire. The soldiers loaded the most grievously wounded, including Byers and the assistant team leader, and it took off in a hurry. Shooting down a helicopter would have been a propaganda victory for the Taliban.

Hunter waved off the second medevac helicopter because the fire was too intense. “We can’t lose a helicopter,” Hunter said. “That can’t happen.”

"It was like a Vietnam movie."

Without another helicopter to shoot at, the gunfire turned on the remaining members of the team. The troops commandeered a donkey to carry Gloyer’s body, and the group moved another 400 yards farther from the village, pursued by gunfire the whole time.

In order to get away, Hunter directed the aircraft and the helicopters to create a “corridor of fire” in the fields between them and their pursuers. The two big Chinooks settled inside this corridor, and everyone remaining climbed aboard.

“They landed, mini-guns blazing, with tracers flying around everywhere. It was like a Vietnam movie,” Hunter said. “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Still firing back, the remaining Green Berets, Afghan commandos, and the rescue team lifted off toward Kunduz as the sun rose.

They learned after they landed at a base south of the city, about 10 minutes away, that Byers had died on the medevac flight back. (He was posthumously promoted to major and awarded a Silver Star by the Army.)

“He was leading from the front — that was what you have to do,” Seidl said. “He was an excellent officer. He would have gone far in the Army.”

After landing, the remaining members of the ODA team stood in a circle, taking in the events of the night. “The sun was up,” Hunter said. “Until you’re safe, you can’t think of all of that stuff. You can’t let it distract you.”

That morning, the civilian casualties began to arrive at Kunduz hospital, borne on carts and accompanied by protesters from the village.

A reporter on the scene from the New York Times counted the bodies of 14 children, four women, two older men, and two men of fighting age. The bodies were later brought to the governor’s mansion in Kunduz by protesters.

“A hole was made in the roof of the room where we were sleeping and fire came from above,” one villager told the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) in its annual report on civilian casualties in Afghanistan. “When I got closer to [his daughter-in-law], I saw that she was bleeding and then she passed away. Her 2-year-old daughter lost both her legs.”

Initial statements varied on how many people were killed in the village, as well as how many Americans and Afghan commandos died. Some news reports put the village on the wrong side of Kunduz, with various sources spelling it Boz Village, Quandahari, Boz Kandahari, or Boz Qandahari. An Afghan Army source told reporters that no Americans were on the mission. A Taliban statement claimed to have killed 15 Americans. NATO’s Operation Resolute Support released a statement later in the day announcing that two service members were killed and two wounded. Byers and Gloyer were now among the 14 Americans killed in Afghanistan in 2016.

The UN report later reported that 32 civilians were killed in the village that night, 20 of them children and six women, and another 36 people injured. The majority of the civilian casualties came from the two compounds at the end of the alley where the munitions depot had exploded. The dead and wounded included 25 members of Mutaqi's family, among them 13 children under the age of 11. Another 15 of these civilian casualties came from the compound with the steel gate, and included four children under 8 years old. The damage assessment found nine damaged buildings, nine possibly damaged ones, and three craters in the village.

Civilian deaths have been an Achilles' heel for US forces in the Afghanistan War, a Congressional Research Service report noted last year. The bombing of a wedding party in 2008 that killed 47 civilians, including the bride, and its denial by the US military, particularly soured relations with the then-president of Afghanistan Hamid Karzai. Karzai later demanded that the US “put an end to civilian casualties” after a second wedding party was bombed. “We cannot win the fight against terrorism with airstrikes,” he said. And the battle to retake Kunduz in 2015 is best remembered for an errant US airstrike on a Médecins Sans Frontières hospital that killed 42 civilians.

Afghans don’t seem to blame the insurgents for civilian deaths they cause, according to a 2013 survey led by Yale’s Jason Lyall, at least among the majority Pashtuns who form the backbone of Taliban support. But they do blame NATO forces for theirs, which increases local support for the Taliban.

While reparations to the families of civilian casualties decrease support for the Taliban, according to the survey, they don't increase it for the national government. At Boz-e-Qandahari, the Afghan government paid 100,000 Afghanis, about $1,450, to family members of those killed, and half that amount to those injured, according to the UN.

The Taliban certainly understand what Lyall's team called its “home team discount.” The insurgents killed four civilians and injured another 131 in a suicide car bombing in the nearby city of Mazar-e-Sharif eight nights after the raid on the village. A statement from the insurgents called the “martyr attack” retaliation for the airstrikes, and the death of Mutaqi, the Taliban leader in the village. The UN suggested the Taliban blast might amount to a war crime.

Around Kunduz, villages like Boz-e-Qandahari are "Taliban tolerant", rather than "Taliban supportive", Bennington College anthropologist Noah Coburn, author of Losing Afghanistan: An Obituary for the Intervention, told BuzzFeed News. To have normal villagers flock to a firefight, rather than running away, would be really unusual, he said, raising the possibility that the Taliban there wanted the fight. “Most villagers are pretty disillusioned with both sides,” said Coburn, who spent five years in Afghanistan, part of it around Kunduz, interviewing locals.

“Counterinsurgency really depends on good local intelligence, which is hard to get around Kunduz,” Coburn said. “It seems like we didn’t have it in this case.”

In January, NATO released a statement finding that 33 civilians were killed in the fighting in Boz-e-Qandahari, different from the UN estimate. “The investigation concluded that U.S. air assets used the minimum amount of force required to neutralize the various threats from the civilian buildings and protect friendly forces,” the statement said.

The battle likely killed 26 Taliban, including three leaders, and wounded another 26, as well. (BuzzFeed News has requested the investigation report but has not received it.)

“This really is a classic case where the US troops probably did things that were heroic and difficult and put them in terrible danger,” said Coburn. “But it is hard to see how this puts things on a path to a political solution.”

For both Seidl and Hunter, that’s beside the point. They only recall fighting people trying to kill them from as close as 9 feet away.

Without the airstrikes and the curtain of protection they provided, “I’d be dead,” Hunter said. “I’d be super dead.” ●

CORRECTION

Maj. Hall was the fire control officer on the AC-130. An earlier version of this post misstated his title.