HUNTINGTON, West Virginia — Nothing is simple in drug court.

“I feel like you and I have been having this little cat and mouse game,” Judge Greg Howard tells a tall, bearded young man seated at the table below him one Monday morning in February.

“First it’s about your employment, whether it was under the table or not. Now it is about whether you are flirting with or dating someone else in the program,” said Howard with exasperation, leaning forward on his judge’s bench as the man nodded and hid a grin.

“I want you to focus on the drug problem.”

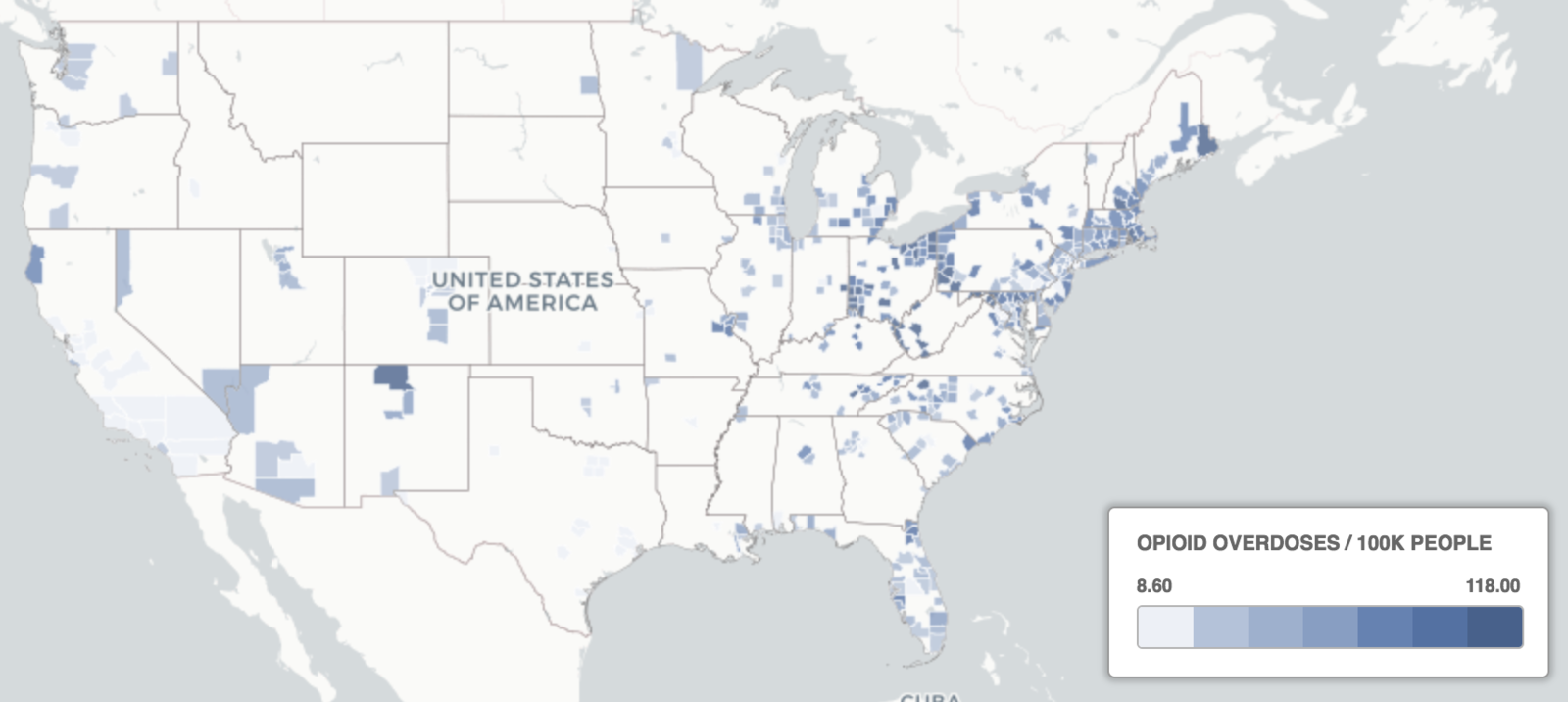

Here, in a beat-up downtown, sandwiched between a noisy railroad and the brown waters of the Ohio River, is the US opioid epidemic’s ground zero — the drug court for this city of 47,000 with an overdose rate 10 times the national average.

These days, Huntington is best known for two things. The first is a cluster of 26 overdoses and two deaths that all happened in a five-hour stretch in the early morning of Aug. 15, 2016, and were all tied to heroin and other opioids. The deaths alarmed public health officials, pointing to the lethality of fentanyl, a synthetic drug roughly 30 times more potent than heroin, and carfentanil, an astonishing 5,000 times more potent than heroin. At the start of the decade, fentanyl overdoses were rare. Now the drug and its chemical cousins are the country’s leading cause of fatal overdoses.

The town’s newer claim to fame is the gripping 2017 documentary, Heroin(e), the story of three Huntington women: fire chief Jan Rader, realtor Necia Freeman, and Judge Patricia Keller, who in 2009 started the county’s drug court, a treatment program that offers people arrested on drug-related charges the chance to have their arrests wiped away, if they can stay off drugs. The film, directed by Elaine McMillion Sheldon, has been nominated for an Academy Award.

There are 28 drug courts in West Virginia, and about 3,000 nationwide.

There are 28 drug courts in West Virginia, and about 3,000 nationwide, serving people arrested on drug charges, as well as prostitutes with drug use disorders. Instead of going to prison, they get mandatory drug testing, addiction treatment, community service, counseling, and the opportunity to turn their lives around.

In October, President Trump gave a speech in Huntington on the opioid crisis, promising to “take the fight to drug dealers.” This tough-on-crime approach has been echoed by Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who said he would “back the blue” in a November speech on the opioid crisis, giving $12 million for increased law enforcement in drug cases. “With one American dying of a drug overdose every nine minutes, enforcing our drug laws is more important than ever,” he said.

But on the ground in Huntington, the reality of the government’s response is far less dramatic, and focused on treating addiction as a disease instead of a crime. Drug courts are a way of chipping away at the problem, with about half of their participants graduating, and the majority of graduates staying clean for years. They work by essentially treating addiction with courtroom theater, a mixture of sternness and kindness.

A day in court exposes the all-encompassing challenge of the epidemic, affecting everything from a child’s birthday party to renting an apartment to getting your nails done, for people with drug problems bad enough to lead to arrest. And how, despite the spotlight of the documentary and overall awareness of the problem in Huntington, overcoming addiction remains overwhelming.

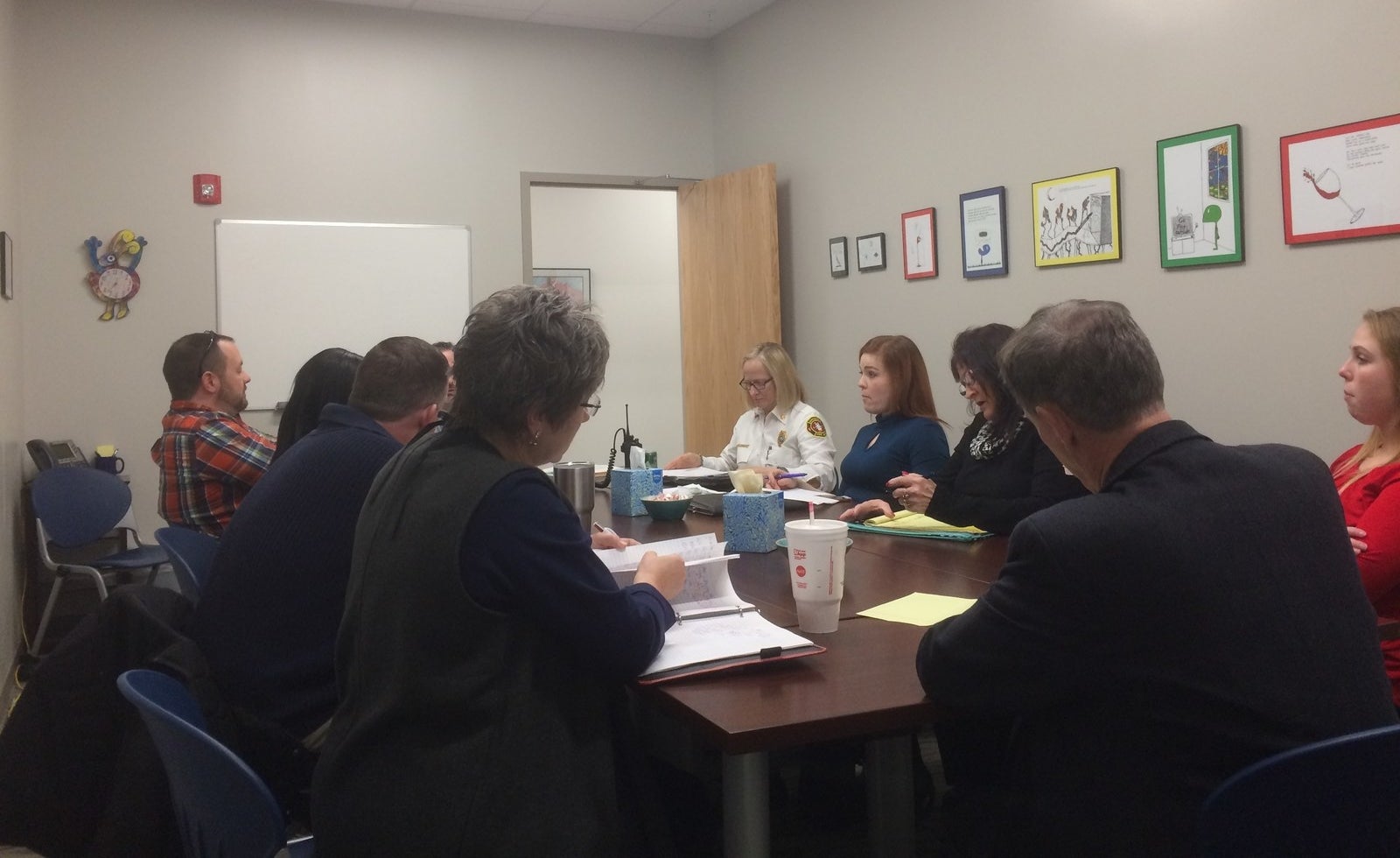

Drug court began that Monday at 12:30 p.m., as more than a dozen people — probation officers, doctors, a therapist, homeless shelter representatives, prosecutors, public defenders, and two of the women stars of Heroin(e) — crammed around a big square table in a meeting room to talk about the previous week’s successes and tragedies, in a world where living a normal life counts as a huge breakthrough.

Since the film debuted, Howard has replaced Keller as the presiding judge of the Cabell-Huntington adult drug court, but otherwise not much has changed. Some 80 people are taking part in the program every year — a small slice of the incredible 10% of the city’s population addicted to opioids. Violent crimes, mostly tied to drug robberies, are rising. And the county still leads the state in drug overdose deaths, with 152 last year.

From her corner of the table, Rader, the fire chief, mentions Alicia, who had overdosed over the weekend. The group recognized the name: She had run away from the drug court program a year and a half earlier, an “absconder.”

“She wasn’t happy when she came to, and saw me,” Rader says. “She tried to give me a false name.”

Everyone shakes their heads. Alicia won’t be given another chance in drug court; she’s headed to jail.

Over the next hour, the group’s conversation is boisterous and unsentimental as they run down the list of 13 women and 5 men who will appear in drug court that day to be questioned, cajoled, rewarded, and sanctioned by Judge Howard. They start with the women, in alphabetical order, who will appear in court first.

“We keep the boys and girls apart,” Keller said earlier that day. “We learned it makes it easier to talk about things that come up in life that way.”

The group is wary of Amber, for example, who was excused from community service because of the flu. “She gets sick a lot,” one of the probation officers warns. And Jessica, who wants to move in with a boyfriend who’s also in recovery, raises more eyebrows. “I don’t think it’s a good idea,” another probation officer says.

The participants under discussion are in their twenties and thirties, typically busted for possession of meth or heroin, theft, or prostitution. Some went to high school in Huntington, some are from other West Virginia counties, and some are from out of state. They are the children of rich and poor alike, swept up in the rural heroin addiction epidemic that picked up steam in Appalachia and New England after the 2008 recession. All of them volunteered for the program and, according to the probation officers, really do want to get off drugs.

Samantha desperately wants custody of her children and, as a result, has been strongly motivated to stick to the rules. Nearly twice as many grandparents are raising grandchildren in West Virginia now compared to 2005, an increase driven by the opioid epidemic.

Running through all the assessments this Monday is a cooking class that the drug court participants took the previous week. Some of them made dessert with the judge. “They didn’t think they would like it, but they did once it got going,” Howard says.

One of the program’s counseling approaches is getting people to do simple stuff together that’s fun and doesn’t involve drugs, whether cooking, pottery, or bowling. Essentially, drug courts are therapy disguised as a courtroom, with the judge ordering people to have fun without drugs, so they become accustomed to the possibility.

The first real problem comes up with Wanda, who has relapsed. Drug court participants have to account for any prescriptions for ailments, even for non–drug-abuse disorders, and she only turned in 83 pills out of 90 prescribed to her the week before. What’s more, she didn’t do enough hours of community service in the last week. The team discusses which doctor prescribed her the drugs and whether to send her back to jail. “She is just a hot mess,” one says.

But the jail is rife with meth, says another. They debate how often drug court participants sent to jail come back clean.

If people who break the rules can’t go back to jail, “where do we keep them?” asked Freeman, a realtor who delivers meals at night to prostitutes through her Brown Bag Ministry.

Nobody has an answer.

The final woman under discussion, Gretchen, lives in an apartment building with drug dealing and prostitution on the stairwells, across the hall from where another drug court participant died of an overdose.

“I could probably shut that building down,” Rader says, because of fire code concerns. But where would the residents go? Typical rent in Huntington is $645 a month, 33% less than the national average, but still a lot for people working part-time while going through drug court. A probation officer tells the judge that the landlord has promised to stop renting to drug dealers, but the group doesn’t seem terribly reassured.

Next, they start on the men. Seth came back from two days in jail still clean on a drug test, which pleased everyone. The next two men likewise don’t pose major problems, one interviewing for a job at an Italian restaurant, and the other unemployed and living in a homeless shelter.

Huntington, where 30% of the population lives in poverty, is not the easiest place for someone with an arrest record to find a job. Once an industrial hub powered by coal and glass, more businesses now close than open there every year.

The group turns to the young man whose dating habits will consume a solid 10 minutes of their time. Drug court participants pledge not to fraternize as a condition of starting the program, but people being people, this isn’t always upheld. The basic worry is that the ups and downs of the relationship will knock people into relapses. And some of the men look at women in the program “as pieces of meat,” complains a probation officer, not good for a program intended to restore self-esteem.

“It’s terrible to allow it, but impossible to police,” somebody says. The judge sighs, and says he’ll remind the participants of the rules and bottom line.

The last man discussed wants to start drug court, but his health is so bad they fear he won’t be able to finish it. Infectious diseases, notably hepatitis C and HIV, accompany the addiction crisis, transferred by dirty needles to heroin users, and he has the latter.

He also needs heart surgery. And on top of everything else, he was bitten by a brown recluse spider in jail. “I don’t know if we would be setting him up for success right now to let him into the program,” a probation officer says.

Huntington sits where West Virginia borders Kentucky and Ohio, two other states hit hard by the drug epidemic. Its downtown is marked by empty windows, many of the stores having decamped to the mall just off the major interstate.

Drug courts exist because sending people hooked on heroin or meth to prison doesn’t work very well. About 59% of them end up rearrested within two years of their release, as opposed to graduates of the drug court, where just 9% are rearrested in the two years after graduation.

Part of the reason is biochemistry. Opioids, whether heroin or prescription painkillers, cause physical dependence for almost everyone who takes them long enough. The brain responds to these drugs by halting the production of its own opioids, natural painkillers that trigger rewarding feelings. That means that after awhile, drug users can’t feel the joys of food, sex, or everyday life.

Locking up drug users in prisons rife with drugs usually doesn’t help. It just throws them into periodic withdrawal, which combines the symptoms of severe flu with overpowering feelings of doom. Plus, at $24,000 per inmate per year, prison costs West Virginia a lot more than drug court’s $7,100 per participant, at a time when the state is losing $8.8 billion annually to costs related to the opioid epidemic.

Drug court participants have all been through chemical detoxification, a short-term medical treatment to get them through withdrawal, but that is just the start of turning a life around. Many are homeless, jobless, and have lost their connections to family and friends. “We are giving them a structure to their lives, most of all,” Keller said. “They are going to learn they have to show up on time to things, they have to do their community service, they have to get up and get to the courthouse.”

The Cabell County Courthouse is actually across the street from drug court. The drug court courtroom is bright and new, with two ranks of chairs facing the judge. The women first wait for Howard in a rough circle to one side. One by one, they will be called to sit at a table beneath the judge’s bench.

The women clap for the first participant called to the front, who’s done well enough to have her location-monitoring bracelet removed. The sick woman, Amber, who looks like she genuinely has the flu, is excused from community service for a week.

Judge Howard next introduces the “Garcia” rule, named after the woman before him, Samantha Garcia, who has turned in a required written essay this morning on time, but too late for the judge to read it over before seeing her. From now on, paperwork has to be delivered by lunchtime Friday.

Next, a woman has her cell phone taken away as a sanction and is put on home confinement at the homeless shelter where she lives.

Fadra, now eight months into the program, tells the judge about how happy she is that she took her son to Chuck E. Cheese’s to celebrate his birthday, with money she saved from work. Her boss has offered her a full-time job as well.

“What I like, and what we were talking about, is that you are at the point where you don’t really care about us, about doing things to make us happy,” the judge tells Fadra. “You are doing this for yourself, and that is how it should be.”

It’s been a long road for Fadra, who told BuzzFeed News she was addicted to opioids for seven years. What made her want to stop, she said, was getting kicked out of her parents’ home with her youngest child, forced to sleep overnight in a homeless shelter.

“I woke up and he was sleeping in the cot next to me. This completely innocent face, and I thought, ‘what am I doing, I’m 32 years old, it’s time to grow up.’”

Last of the women is Gretchen, who has spent $30 on two skull rings and a manicure, which the judge asks to inspect while she blushes. The money for the rings was a birthday gift from her mother, she tells him.

The judge tells her to look for another place to live and to quit looking for a longer-term lease at her current apartment building. Before dismissing her, he asks what happened to the skull missing from one of her rings. She confirms she lost it while working at the hamburger restaurant.

“I hope nobody ate it,” he says.

The men sidle into the courtroom with less energy, dressed in baggy jeans and close-shaved haircuts. They are first told one of their number has been returned to jail, and they look unsurprised.

As they each appear before the judge, they are brusquely polite (“yes sir, no sir”) in the manner of people who have been locked up, comprehending they are inside the machinery of the legal system, despite the cooking classes and the bowling.

Seth was removed from the court in handcuffs in January and sent to jail after he took drugs. Now he tells Judge Howard that two days in jail was enough for him, and the judge commends him for his attitude. Cory, who landed the Italian restaurant job offer, is given a choice of a gift card as a reward. When he selects one for a grocery store, the judge salutes him for making a practical choice. Matt, the man not looking hard enough for a job, gets a scolding.

Finally, J.P., the tall young man whose dating habits caused so much discussion, comes in for a critique from the judge, who is unhappy that someone only seven weeks into the program is causing him aggravation. “Just focus on you and your kids,” the judge says. “I’m not going to babysit you for 52 weeks.”

With that, court is dismissed. Rewards, sanctions, and strictures are handed out, and the participants go back into the world for another week.

Afterward, when asked if he learned anything from other people in drug court, Seth snorts. “I don’t learn anything from them,” he told BuzzFeed News. “I learn what not to do.”

The one thing he has figured out from drug court, he says, is, “you really have to want to change. They can’t do that for you.” He is very aware of the 50-50 odds of graduating, and how that would lower his odds of dying, he says. “I want to change.”

CORRECTION

Two of the women stars of Heroin(e) — Jan Rader and Necia Freeman — were at the pre-court meeting, but Patricia Keller was not.