An Ohio couple overdosed in a car while a grandson waited in the backseat. A North Carolina couple did the same with their 3-year-old in tow. A toddler wailed with her overdosed mother sprawled on a grocery store floor.

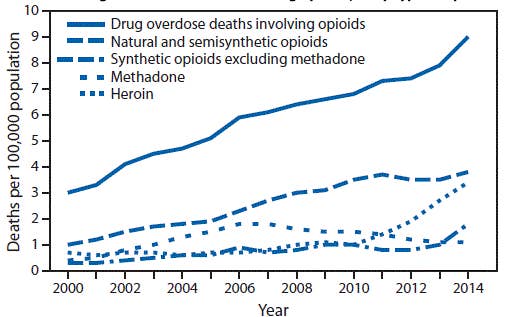

Graphic photos and videos of these scenes were released by police departments this fall in a desperate attempt to bring attention to the nationwide heroin and painkiller epidemic. As the rate of opioid overdose deaths has risen sharply — tripling between 2000 and 2014 — so too has the response from the right wing. Whereas just a couple of decades ago, conservatives’ response to drug addicts was to throw them in jail, they’re now aligned with liberals in calling for more treatment.

What they don’t agree on, however, is how.

Take Newt Gingrich, former U.S. House Speaker and wannabe VP pick for Donald Trump. Gingrich agrees with politicians, such as New York State Republican Senator Robert Ortt, calling for repeat overdose survivors to be forced into treatment programs.

“If you overdose twice, at that point you are truly out of control of your life, and therefore we have an obligation as a society to help you get back in control of your life,” Gingrich said on Monday at an American Enterprise Institute forum put on to promote his advocacy group, Advocates for Opioid Recovery.

“I don’t have very much sympathy with the civil liberties argument that your right to be saved 10 times means the rest of us have to pay for the ambulance once again to save you at the last possible second, until the time we don’t get there. And then you die,” Gingrich added.

One bill that Ortt advanced last year extended the time that hospitals can keep a patient after an overdose — from 48 to 72 hours. Another bill, which would allow a doctor to require that an addict get treatment after overdosing, did not pass, but Ortt plans to reintroduce it next year.

“I don’t dispute that voluntary treatment is better than forced treatment. That’s for sure,” Ortt told BuzzFeed News. “But forced treatment has a higher success rate than no treatment, and these people are overdosing multiple times.”

Most social workers and drug researchers, on the other hand, disagree, warning that addicts will stop calling ambulances if it leads to something that feels like jail.

“We know coercion doesn't work,” psychiatric epidemiologist Jay Unick of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, told BuzzFeed News. “The more we criminalize behavior, we start doing this, we drive it underground, and people don’t ask for help when they overdose.”

At the forum where Gingrich spoke, his fellow addiction treatment advocate Van Jones, a former Obama White House green jobs adviser, expressed similar misgivings about the “unintended consequences” of forcing overdose patients into treatment. And Gingrich himself called the checkered US history of forcing people with mental health issues into badly run state facilities a reason for caution, saying that addiction needed to be treated as a disease, not a crime.

Scientific research has shown what works best: “medication-assisted treatment,” or combining years of milder opioid medications with frequent psychological counseling, said psychiatrist Sally Satel, an AEI scholar who moderated the panel with Gingrich and Jones. Programs that offer serious consequences to addicts who relapse, such as lost jobs or stricter monitoring, have even better results.

“I’m in favor of what works,” said Jones, who started advocating for addiction treatment after the April death from an opioid overdose of Prince, who was a longtime supporter of Jones’s charitable efforts. Jones was one of the few attendees at the private memorial service for family and friends of Prince after his death.

“Someone I was a close friend with died. I didn’t see it coming. I didn’t see the signs. I carry a lot of guilt with me,” Jones said at the event. “My world got turned upside down, and there’s a lot more out there we need to work together on.”

Although there is now broad bipartisan agreement that addiction should be treated like a disease rather than a crime, a political fight looms after the election over how much to put toward funding a bill, the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which would expand addiction treatment nationwide. A 2015 analysis by federal health officials found only 10 states had enough beds for addicts seeking effective long-term addiction treatment.

The White House has called for $1 billion to fund the bill, and both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump have applauded its passage. But the House, led by Republicans worried about the federal budget, has called for only $500 million.

Effective addiction treatment is time-intensive and expensive, Ortt points out, with each new bed at an addiction treatment center costing states like New York more than $200,000.

“Ultimately we are going to have to pay for treatment,” Ortt said. “But I can tell you that [treatment] is a lot cheaper, and a lot better, than jail or an emergency room.”