China’s fertility treatment shortage, as well as the desperation of HIV-positive couples there to have a child, appear to have been the key that opened the door to the world’s first reported gene-edited people.

Intense controversy and scientific condemnation has followed last week’s announcement of the birth of twins Lulu and Nana, carried out by biophysicist He Jiankui of China’s Southern University of Science and Technology. Their birth was the result of a campaign that initially recruited as many as 200 couples, according to Chinese media reports, all of which included a man who was HIV-positive.

The couples were taken advantage of, according to biochemist Fang Shimin of China’s New Threads magazine (better known by his pen name Fang Zhouzi), an award-winning critic of scientific misconduct in that country. He told BuzzFeed News an ethics review of the experiment signed off by a small for-profit hospital was “a joke,” and suggested that parents likely couldn’t understand the consent forms for the experiment. “I doubt Dr. He himself fully understands the consequences and risks,” Shimin said, by email.

He declined to comment for this story. In a presentation he gave last week at a scientific summit in Hong Kong, he said the informed consent process was thorough, and that he spoke to each couple in person, line by line, to ensure they understood the risks and benefits of the procedure.

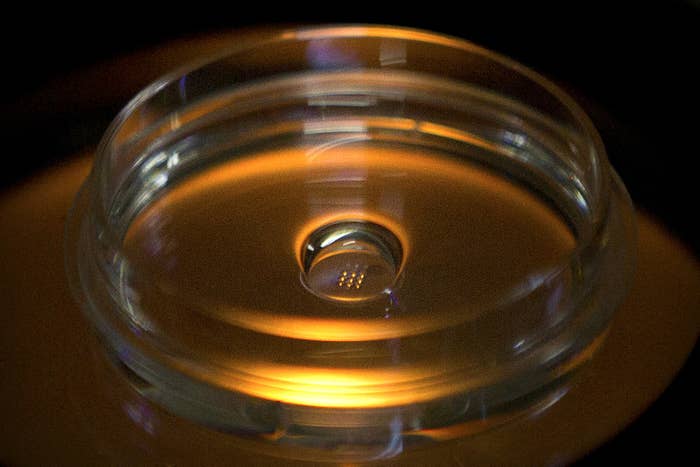

A 2003 regulation in China prohibits gene editing of human embryos for reproduction. Nevertheless, according to He’s presentation last week, his team made eight couples an offer: If they joined the gene-editing trial, they would get a fertility treatment that included a procedure to wash HIV away from sperm, in order to ensure that the child did not contract the disease. (One couple dropped out.) The sperm-washing method with IVF has for decades been the gold standard for preventing transmission of the virus to children in couples with a father who is HIV-positive.

But in China, infertility treatment is hard to come by for parents in such a situation. Tens of millions of people in China have infertility problems, one study estimated. But the country has only one fertility clinic for every 7.5 million people, making them about 10 times rarer than in the US, according to a 2014 survey. Then there are the high costs: about $16,000 for the IVF, on average, plus another $20,000 for sperm washing — prohibitively expensive for most couples.

On top of that, China has laws against some IVF procedures, aimed against selecting for sex or beneficial genes. And the genetic testing of an embryo before it is implanted in a woman’s uterus, performed in He’s experiment to measure whether gene-editing took place, is only permitted for serious diseases. Sperm washing is also a method for sex selection, making its use in the experiment legally murky in China, according to an expert.

“Parents are so desperate, the lines are out the door at [fertility] clinics,” lawyer Stephanie Caballero of the Surrogacy Law Center, PLC, in Carlsbad, California, which works with many parents in China looking to the US for surrogate mothers every year, told BuzzFeed News.

One couple of the eight dropped out of He’s experiment. They told the Chinese magazine LifeWeek that He did not tell them that China has guidelines against gene editing. They said they were interested in his offer because they couldn’t afford IVF treatment.

“I turned them down, because I didn’t want to be a lab rat,” said the husband, Zheng Xiao (a pseudonym used by LifeWeek to protect him from harassment). A researcher on He’s team revealed that the gene editing was experimental only after they had recruited the couple from a small town in China to what was billed as an HIV vaccine trial.

Zheng told LifeWeek that he and his wife felt the researcher had downplayed the risks of the experiment by saying that the advantages would be greater than the risks. And if there was a problem with the baby, Zheng was told, the researchers would help them “take care of it.”

Zheng said he and his wife weren’t sure what the researcher had meant by “take care of it,” as the Chinese phrase can be interpreted as getting rid of something. So they pulled out of the trial.

“We can’t know whether the baby is growing healthily until it’s born. If it really is unhealthy, how would they get rid of it exactly?” he reportedly said to his wife, who was also having doubts about whether the process would be painful.

Medical research ethics preclude offering experiment volunteers excessive inducements, bioethicist Insoo Hyun of Case Western Reserve University told BuzzFeed News. “I would argue offering someone a child is excessive,” he said.

Both the US National Institutes of Health and the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences have condemned the experiment, which violated a 2015 moratorium on human gene editing to create the twins.

Couples with less education are going to have trouble understanding the complex science involved in the experiment, embryologist Zhao Zhang of the Carnegie Institution for Science in Baltimore told BuzzFeed News. It would be tough for even college-educated people, he added, calling the experiment “horrifying.”

The founder of an HIV assistance group called Baihualin (BHL) China League, who calls himself Bai Hua, expressed regret on Friday for helping recruit parents to the experiment, saying he was worried about the families and the children. Dr. He had contacted him in April of 2017 to recruit patients, Hua said, and he agreed, despite misgivings about the researcher’s state of knowledge about HIV and the country’s infertility laws. BHL’s initial advertising of the project didn’t tell couples they were being recruited for an experiment. So many applied — 200 couples, 10 times more than what they had expected — that recruitment ended early.

The gene editing in the experiment was aimed at deleting CCR5, a gene for susceptibility to HIV. He defended his experiment at the conference last week by noting high rates of HIV incidence in some Chinese villages — and widespread stigma for HIV patients — as well as an ethics review conducted by a small Chinese hospital. HIV prevalence is low overall in China, but some regions have severe rates of infection.

Both gene-edited twins were healthy, He said, and a second early pregnancy was underway. The experiment itself was halted by his university, however, and there is dispute in scientific circles over whether the gene edits were all successful or safe.

Gene deletions made on #CRISPRbabies don't match the delta 32 mutation, according to @RyderLab. https://t.co/0e9ssW40Ju https://t.co/BGDP5P6itw

More than 100 Chinese scientists denounced the experiment, calling it “crazy,” dangerous, and unnecessary in a statement. Their counterparts in the US are equally outraged, Zhang said, seeing the experiment as an indelible black eye for the Chinese scientific enterprise.

“This case will undoubtedly do further damage” to the reputation of Chinese scientists, said Shimin of New Threads. “It proves that some Chinese scientists are indeed doing wild Wild West style research and the government has little interest to regulate it.”