WASHINGTON — A congressional committee chairman, Rep. Lamar Smith of Texas, considered jailing the attorneys general of New York and Massachusetts at a hearing on Wednesday, displeased by their failure to respond to his subpoenas.

The House Science Committee hearing was called by Smith to discuss his July subpoenas of the state legal officials, attorneys general Eric Schneiderman of New York and Maura Healey of Massachusetts, who did not comply.

Schneiderman and Healey are conducting fraud investigations of ExxonMobil, asking whether the energy titan misled investors about its internal research, done since the 1980s, confirming the dire future consequences of burning fossil fuels.

Smith, a Republican and climate science doubter, says that the Exxon probe could discourage corporations from conducting research on possible harms of their products, a “chilling effect” that might damage US science.

“Such investigations may have an adverse effect on federally funded research,” Smith said at the hearing, explaining why he subpoenaed the state investigators and nine environmental groups he viewed as illicitly collaborating with the fraud investigation. “The refusal of the attorneys general to comply with the subpoenas should trouble everyone.”

The hearing bubbled with sharply divided views between four Constitutional lawyers, three called by Republicans and one by Democrats, over whether (and how) Congress could legitimately intrude into such state investigations, an unprecedented legal move.

Two conservative legal scholars who appeared before the panel called for charging the attorneys general with “contempt of Congress,” which carries a penalty of a year in jail.

“Send out the Sergeant at Arms to arrest someone,” testified attorney Elizabeth Price Foley of the Florida International University College of Law. She argued that Congress has ceded too much power in the last century to federal courts. “I think you should,” she said.

But the lawyer called by the Democrats, Charles Tiefer, fired back. “Your position is entirely without constitutional and legal merit. It is simply bogus,” he testified. “No federal judge could ever be expected to uphold such an indictment and send an Attorney General to prison.”

The only avenue outside of federal courts and prisons for Smith to pursue contempt charges comes from “inherent” Congressional legal powers not used since the 1930s. But in order to do that, Congress would have to set up its own court — and, if the attorneys general were found guilty, Tiefer added, rebuild its jail.

Congress used to have a jail, dating to 1795. It held miscreants who tried to bribe lawmakers, and once, in 1927, Congress arrested the brother of a federal attorney general who refused a subpoena during the Teapot Dome scandal. But the original jail room was turned into a cafeteria in 1858, and Congress doesn’t own prison cells anymore. “Some people say the kitchen hasn’t really changed,” Tiefer joked at the hearing.

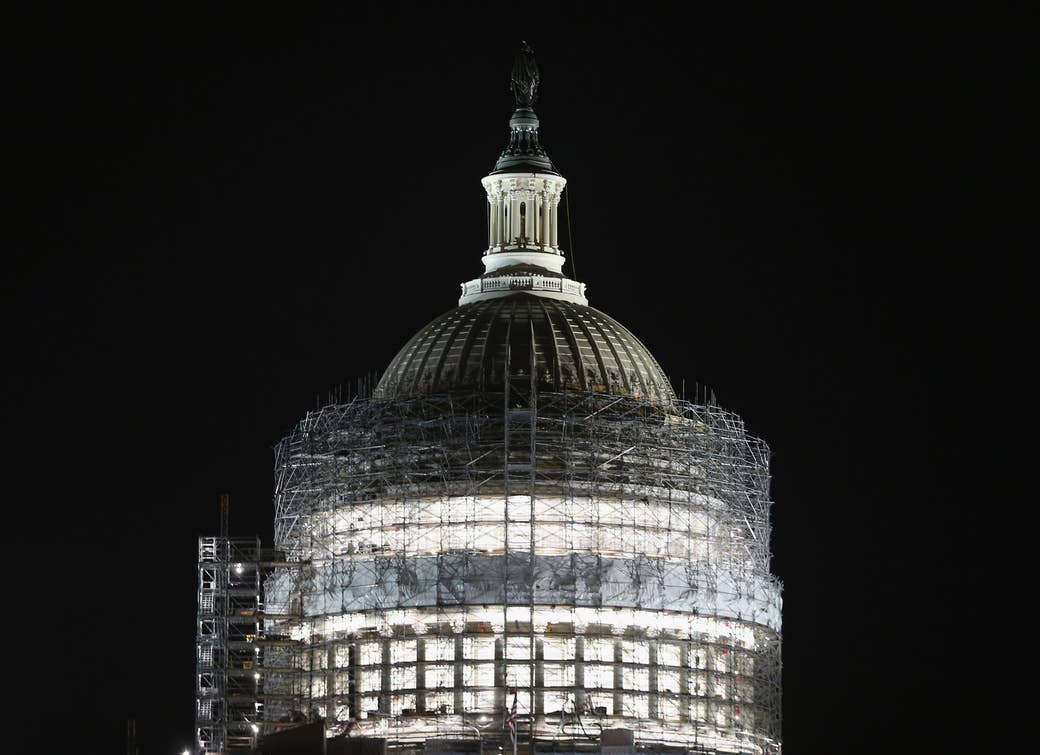

(Another Capitol Hill “guard house” was turned into a Post Office after 1902, and a barred, unoccupied tomb enclosure for George Washington under the Capitol is sometimes mistaken for a jail cell. The last Hoover Administration official held for contempt in the 1930s was kept at the nearby Willard Hotel.)

Legal scholar Jonathan Turley of George Washington University, who said he supports climate science, testified that Smith could eventually enforce the subpoenas in criminal courts, disagreeing with Tiefer. But he said that it would be better for everyone to privately compromise on the subpoenas, limiting the number of documents that the committee would receive from the state officials about Exxon.

"No amount of congressional grandstanding will change the simple fact that the Committee has no lawful basis to interfere with a state law enforcement investigation,” Schneiderman spokesman Eric Soufer said in a statement sent to BuzzFeed News. “Today's farce of a hearing was just another example of Big Oil using the Big Tobacco playbook to deflect, delay, and distract from the real issues under investigation."

So why is an obscure Congressional committee debating the intricacies of subpoena law?

What’s really at stake are fears by allies of the energy industry — acknowledged by witnesses and lawmakers at the hearing — that the attorneys general are staging a replay of the 1998 tobacco industry settlement that yielded 46 states some $206 billion, after it became apparent the industry had misled smokers about cancer risks from cigarettes for decades despite their own medical research. In July, Smith called the current Exxon investigation “extortion” by the attorneys general.

During the 1990s tobacco investigation, the governor of Mississippi unsuccessfully sued his own state’s attorney general to hinder the case, legal scholar Colin Provost of University College London noted to BuzzFeed News. Smith’s subpoenas appear to follow a similar track, Provost suggested.

Last year, investigations by Inside Climate News and the Los Angeles Times showed that Exxon scientists had warned the firm about global warming as far back as the 1970s. Schneiderman and other critics of Exxon have drawn parallels to tobacco firms misleading smokers.

At the hearing, Turley said that he didn’t see Exxon’s climate research as analogous to tobacco firm research on lung cancer, calling that view “an overreach.”

However, former Justice Department attorney Sharon Eubanks, who headed the successful 2005 federal racketeering case against tobacco firms, told BuzzFeed News, “I see them as the same.” Extra power to pursue stock market abuses given to New York’s attorney general give Schneiderman extra leverage, she added.

Provost said that most likely, any attempt by Smith to enforce his subpoena would eventually end up in federal courts, where he agreed with Tiefer that judges would rule in favor of the states. “The attorneys general have broad authority to investigate in the public interest, authority which has generally been upheld by the courts.”

A side question at the hearing was whether Smith would also go after the nine environmental groups — such as the Union of Concerned Scientists and the Rockefeller Foundation — who also did not comply with his subpoenas. Ironically enough, Turley said, those groups have echoed Exxon’s free speech arguments against responding to subpoenas from the state attorneys general.

Both Exxon and the Attorneys General are citing the 1950s communist witch hunts on Capitol Hill to justify ignoring requests for documents, said Turley. “I don’t think either side of this wants a return to the Red Scare.”