BuzzFeed News has reporters across five continents bringing you trustworthy stories about the impact of the coronavirus. To help keep this news free, become a member and sign up for our newsletter, Outbreak Today.

WASHINGTON — Outside the grocery store in Congress Heights, people are playing dominoes in the parking lot, close together without wearing masks. An auto service truck driver, who’s come to repair a flat tire, isn't wearing a mask either; he says he's had pneumonia and survived getting shot already, so what is the coronavirus to him?

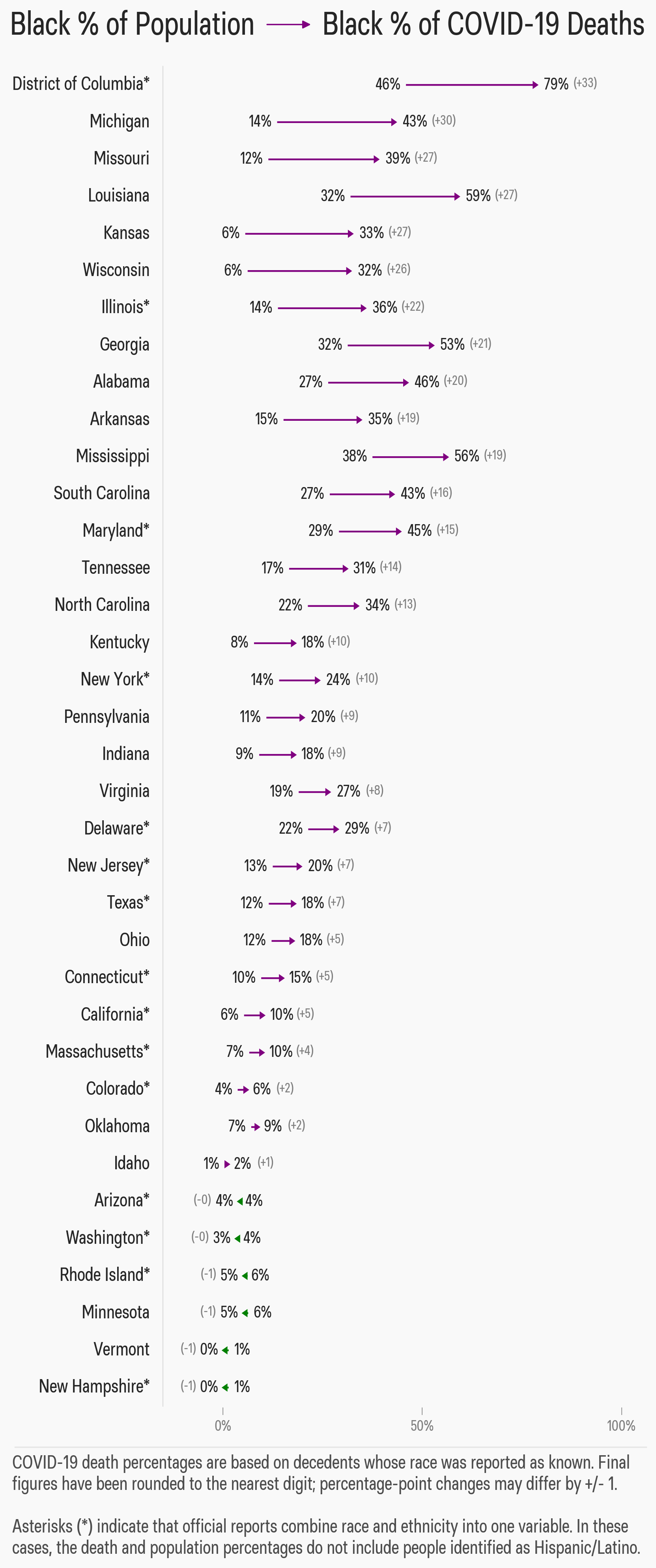

In Washington, DC, a city that is 46% black, close to 80% of coronavirus deaths so far are among black people.

And black people are dying at higher rates than virtually anyone else across the US.

The coronavirus has been especially deadly in black neighborhoods in cities like Chicago, Milwaukee, and New York. With US case numbers now surpassing 1.1 million people, the stark racial disparity was most recently on display in Richmond, Virginia, where 62% of COVID-19 cases were among black people in a 52% white city, while all eight people who died of the disease in the city were black.

Last week, Sen. Kamala Harris of California introduced legislation to create a federal task force to investigate racial disparities in coronavirus deaths. "Early reports overwhelmingly show that COVID-19 is disproportionately infecting and killing minorities across the nation,” Harris said.

Black people in the US already have worse health outcomes, even predating the pandemic. Black men have a life expectancy of 71.5 years, below the national life expectancy of 78.7 years. Black people have higher rates of heart disease, diabetes, and other stress-related illnesses — all among the “comorbidities” that raise the risk of dying of COVID-19 — and have reduced access to healthcare to help prevent and treat them. They are also disproportionately performing the low-paying “essential” jobs that increase risks of exposure to the novel coronavirus.

The disparities have led some commentators to argue that black people need to take better charge of their health to stem the tide of deaths. But decades of mistreatment — whether it’s being denied care at white hospitals as recently as the 1960s or being denied pain medications by racist doctors today — have created a structural wall of suspicion of the medical system, as well as a deep stigma underlying the notion of being sick.

“You can’t just parachute in now to tell people you are going to help them with a pandemic when they have been neglected so long,” Martin Pernick, a medical historian at the University of Michigan, told BuzzFeed News. “They’ll ask, ‘Where were you when my child was sick or dying of something else?’ and even with good intentions, you can’t blame them.”

This is dressed up bootstrapped-ism that maintains inequality by suggesting people can overcome systemic and structural racism if they simply tried harder. Giving a nod to those inequalities and then dismissing them by pointing to personal responsibility is part of the playbook. https://t.co/OsqnpjZpSE

This distrust of healthcare is born out of medical racism going back to the slavery era, Pernick said. Physicians were employed to ready slaves for auctions and performed cruel surgical experiments on them without raising the question of consent — memories that are buried but still running deep, an undercurrent of skepticism toward medicine in long-neglected communities.

Much of the suspicion around abuse in human experimentation is rooted in the infamous Tuskegee experiment, said Sheila Murphy, a health communications professor at the University of Southern California, who has looked at why black people volunteer less often for clinical trials. The 40-year experiment, which ended in 1972, involved government researchers leaving 600 black sharecroppers deliberately untreated for syphilis even after the discovery in 1947 that penicillin could cure the disease. Twenty-eight of the men died of syphilis and another 100 died of related complications.

“Every time I work with this population, if they are over 20, they are well aware of Tuskegee and very leery of participating in clinical trials,” said Murphy. “Unfortunately, this means that some drugs might reach the market without being tested specifically on African Americans who may have unique side effects.”

Over 1,100 coronavirus clinical trials are currently underway in the US, and the FDA has approved emergency use of the antiviral drug remdesivir to treat COVID-19 after preliminary results from small trials for the experimental drug suggested it could shorten hospital stays. Large vaccine trials are expected to start in the fall.

Medical racism still persists today. Doctors in one 2016 survey still subscribed to the slavery-era belief that black people feel less pain than white people do, and a 2007 University of Pennsylvania survey across 20 major US cities found that black people distrusted doctors more than white people did in all but three cities — Las Vegas, San Antonio, and Riverside, California.

“Because we know that often, African Americans — their pain is not recognized or seen as bad. That can lead to issues in terms of whether or not they’re seen as having a severity that warrants certain next steps,” Lillie D. Williamson of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, whose work looks at the relationship between medical mistrust and experiences of discrimination, told BuzzFeed News.

BuzzFeed News has reported several cases of black people in the US who have been denied COVID-19 tests despite showing symptoms, having underlying conditions, and asking for tests.

Williamson suggested medical mistrust increases as more people hear those stories. As more news comes out about black Americans seeking medical attention and being turned away, Williamson said, we need to consider “what that does for individuals as they consume that, and what that means for people’s willingness to seek help.

“People feel like, 'What’s the point? I already know I can’t trust physicians, look at all these examples,’” added Williamson, noting that this view doesn’t represent all black Americans.

Due to years of mistrust, communities of color may lack familiarity with the healthcare options that are available, physician Janet Seabrook of Community HealthNet Health Centers in Gary, Indiana, told BuzzFeed News. “The misinformation, disinformation, and wishful thinking run rampant,” she said pointing to a dangerous rumor in early March that black people cannot contract COVID-19.

In her own family, she had to convince an older relative to seek treatment for prostate cancer; as a boy in the Deep South, that relative saw that almost as soon as someone learned they had cancer, they died.

"Imagine trying to get my family member in a clinical trial if I were not in the picture,” said Seabrook. “Imagine what would have happened to this family member without a resident doctor in the family."

There’s also a stigma associated with the virus, which some are comparing to the wave of deaths from the AIDS epidemic. One New York resident, W.C., who asked to be identified only by initials to discuss her medical status, said she fears being judged. When W.C. announced that her grandmother died on Facebook, she did not mention it was from complications related to COVID-19, nor did she announce that she and her mother had also tested positive.

“The only reason people are not talking is because they are taking it like it’s AIDS, and it’s really not like that,” W.C. said. “That’s why I tell people, ‘You sitting here scared to talk about it, and you could be somebody that got it and don’t even know it.’”

Robert Cornegy, a New York City Council member who represents a large black population in Brooklyn, said he rejects the idea that his constituents take social distancing any less seriously because of a distrust in medicine. At the same time, he chose to keep his own COVID-19 diagnosis private.

“I think that people were very confused about the disease, very confused in conflicting stories around who it would impact negatively. So I didn’t want to play into that,” Cornegy told BuzzFeed News. “I know what the fears are of people, and they have a reasonable expectation that their leadership will keep themselves healthy and be able to pull the entire community along.”

That community is being hit hard. As is the Bronx, the borough that in early April was projected to lead the city in COVID-19 deaths; some lawmakers have attributed the spike to insufficient testing in the borough's most vulnerable communities. On Wednesday, a JAMA Network report looked at COVID-19 hospitalizations across every borough of New York City, where about 17% of all US cases had occurred by late April. The Bronx, which has the highest share of racial and ethnic minorities, the most people living in poverty, and the lowest levels of education of all New York City boroughs, had the highest rates of hospitalization and death related to the novel coronavirus.

“People who are prepared to help will have to meet black communities halfway by asking them questions about what help they need — not just what they want to give them now and then walking away,” said Pernick, the medical historian. “They will have to overcome an understandable legacy of suspicion.”