The journalists at BuzzFeed News are proud to bring you trustworthy and relevant reporting about the coronavirus. To help keep this news free, become a member and sign up for our newsletter, Outbreak Today.

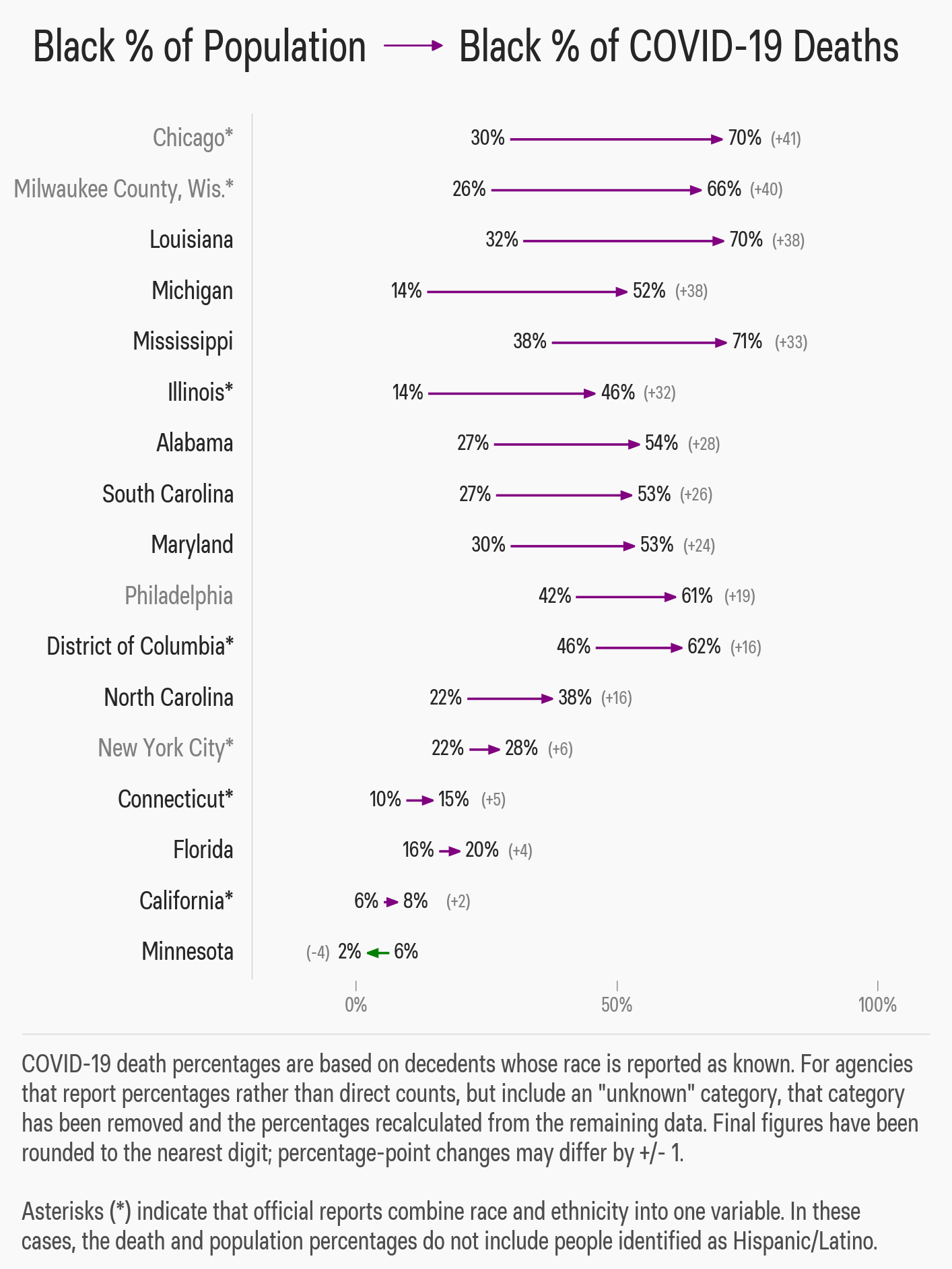

In Milwaukee, Chicago, New Orleans, and all over the nation, the coronavirus pandemic has thrown the long-running racial divide in the health of Americans into stark relief, seen in the outsize numbers of deaths among black populations in hard-hit cities and regions.

“Health disparities have always existed for the African American community,” Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said at the White House on Tuesday, responding to a flurry of news reports of black patients dying in larger-than-expected numbers. “Here again with the crisis, how it’s shining a bright light on how unacceptable that is because, yet again, when you have a situation like the coronavirus, they are suffering disproportionately.”

For a variety of reasons, including a greater likelihood of working jobs that put them on the frontline, decreased access to health care that starts them out with more illness, and crowded living conditions that facilitates the virus spread, the coronavirus has been especially brutal in black communities.

Lawmakers from both parties are now calling on US health officials to release racial data on novel coronavirus cases and deaths nationwide, pointing to dramatic differences in hotspots across the country. On Wednesday, the heads of the Congressional Hispanic Caucus, Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus, and Congressional Black Caucus, called on Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar and CDC Director Robert Redfield to release and analyze such data. That followed Sen. Tim Scott, a South Carolina Republican, making a similar request on Tuesday. “In recent days, a number of concerning reports have emerged, suggesting COVID-19 has had a particularly harmful impact on communities of color,” Scott wrote in his letter.

A week earlier, a group of House Democrats made a similar request, spurred by reports of more than a third of cases in Milwaukee striking black residents.

“It’s hard to tease apart all the threads, and ultimately they all come down to the same thing,” physician Janet Seabrook of Community HealthNet Health Centers in Gary, Indiana, told BuzzFeed News. “What we are seeing is not surprising, and it really comes down to a lack of resources and lack of health care delivering the numbers we are seeing right now.”

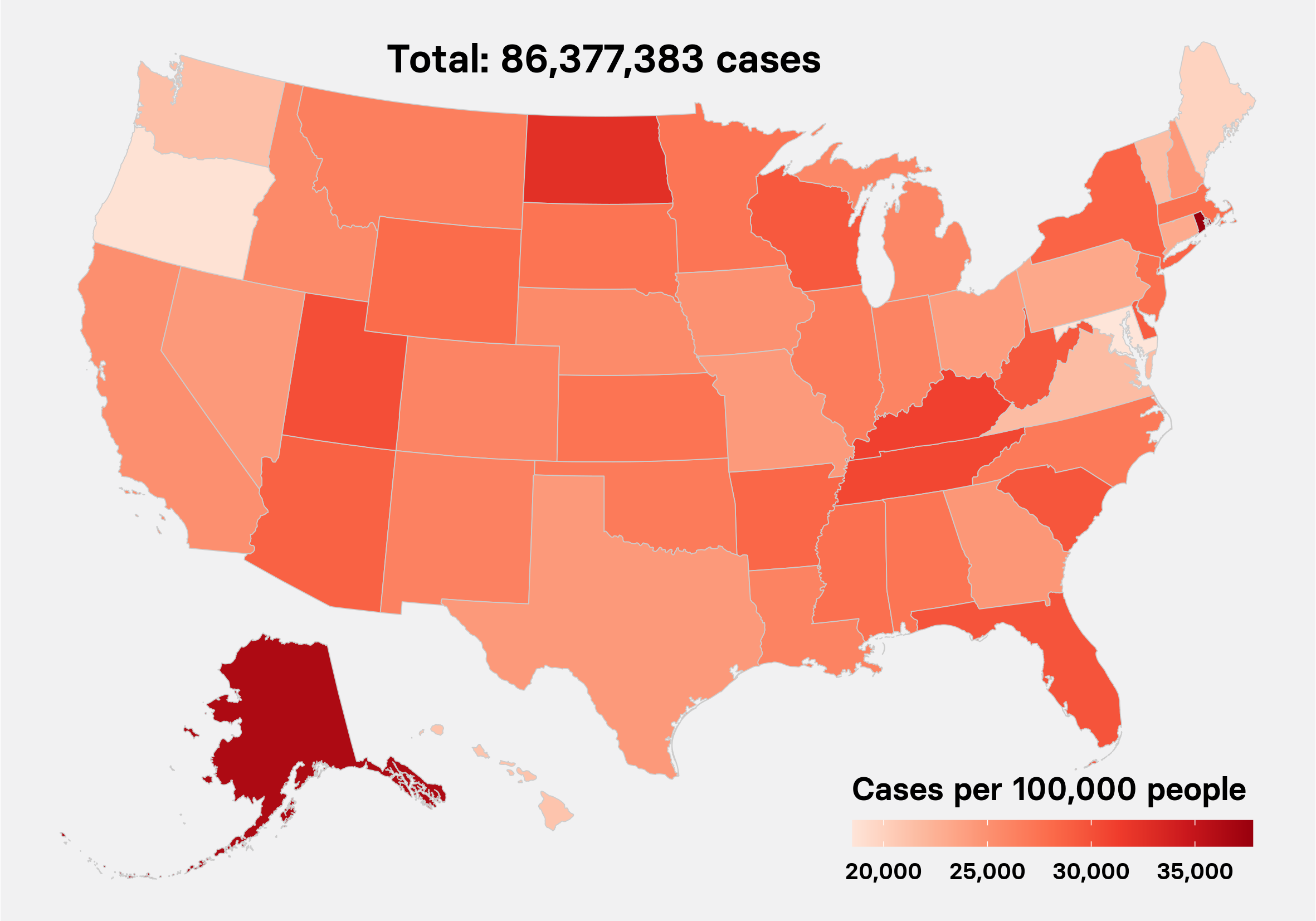

As of Thursday, there have been more than 454,000 confirmed cases of the novel coronavirus across the US and almost 16,000 deaths. The racial disparity accompanying the US outbreak of the pandemic illuminates the medical challenges that black communities, and other communities of color, including Latinos and Native Americans, face every day:

Dangerous Jobs

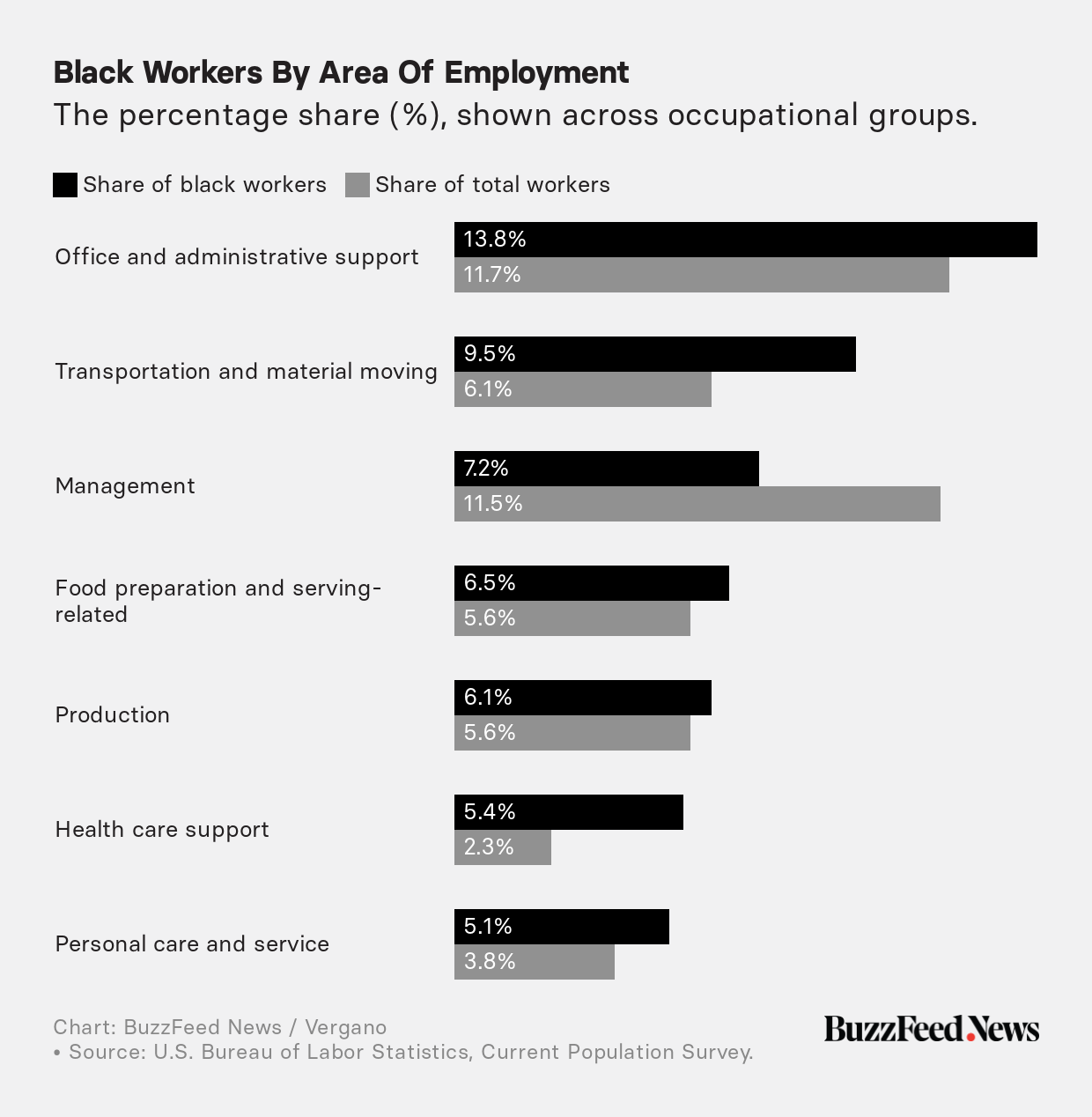

“You can’t drive a bus or wash dishes on Zoom,” Oscar Alleyne, a public health expert with the National Association of County and City Health Officials told BuzzFeed News. “These are people we count on to do essential jobs, and they are going unprotected.”

A lot of the people most at risk for catching the novel coronavirus are the ones in service jobs who can’t avoid contact with the public, exemplified by Detroit bus driver Jason Hargove, who died this month from coronavirus complications after he made a video that went viral in March discussing people coughing on his bus.

“People of color are often working in service jobs, cashiers, nursing, home health aides. These aren’t jobs you can phone in,” said Seabrook.

Bureau of Labor Statistics data shows black people work a disproportionate number of jobs as health care and personal care assistants, for example. Such jobs lead to exposure with potentially sick people, which is even more risky for people who aren’t wearing hospital-grade protective gear.

“Someone has to do these jobs, but people in service jobs just have a higher risk,” said Seabrook. These are people more likely to take cold medicine to knock down a fever and head to a job they can’t afford to lose.

Even before social distancing orders in states nationwide led to the staggering unemployment claims with millions now out of work, the unemployment rate for blacks was already higher, at 6.7%, against 4% for whites in March, which means they have less freedom to just quit their job.

And black people have less savings, with the median worker having only 9.5% of the median wealth that whites did in 2016, which means they have little to survive on if they did quit. That means putting off a doctor’s visit if paying for food or rent comes first, said Alleyne. “We’d really like to see more [coronavirus] data from more cities overall, but poverty is generally a risk factor in health care.”

“They are far more likely to be taking mass transit to get to work because they are less likely to have a car,” said Alleyne. “That’s also a risk.”

Worse Health

At the White House briefing, Fauci worried about greater rates of high-risk illnesses among black people, saying, “The diabetes, hypertension, the obesity, the asthma — those are the kinds of things that wind them up in the ICU and ultimately give him a higher death rate.”

Health experts say such preexisting conditions are widely linked to reduced access to health care among black people, with 11% uninsured against the national rate of 7% in 2017, as well as higher rates of obesity.

“I am worried about the Deep South when I look at where this is going and where we will be looking next,” said Seabrook. Many black Americans in the South live in states that did not expand insurance after the passage of Obamacare at the start of the last decade. The region coincides with the “Stroke Belt” across the southeastern US, where there is a 50% higher risk of a deadly stroke, compared to the rest of the country, and an even higher risk for black people living there. The observation is linked in studies to higher rates of diabetes, heart disease, and smoking, as well as less access to health care in general.

Physicians in Virginia have already complained about a lack of coronavirus testing in black communities during the pandemic, where missing a few cases in states that have cut public health agencies’ budgets for decades could lead to an unchecked outbreak. For example: Albany, Georgia, is still struggling with an outbreak tied to a single infected person attending a funeral. In the city, 1 in 90 people have been infected. Approximately 90% of the fatalities in Albany by March 30 had been in the city’s black community, according to the New York Times.

Worse Housing

“I’m seeing patients who live with grandparents, who sleep in rooms with bunk beds,” said Seabrook. “If you get sick, they don’t have a guest room to isolate you in. It’s very difficult.”

Black and Latino families live in crowded multigenerational homes at much higher rates (26% and 27%, respectively) than white families (16%), according to the Pew Research Center. More than 60 million Americans live in multigenerational homes, where young asymptomatic people might put their older relatives at risk. Worries about this scenario drove a lot of school closings, despite the lower risk to the young from the coronavirus.

.@NYGovCuomo says the racial disparities in who has died from the coronavirus raises lots of questions. "It always seems like the poorest people pay the highest price. Why? Why is that?” One question is whether essential workers are disproportionately non-white.

As well, black and Latino homes are more likely to be in communities with worse air quality, according to the American Lung Association, driving up rates of asthma, another risk factor for severe cases of COVID-19. A Harvard University study released on Sunday suggests that counties with worse air quality standard would see an increased coronavirus death rate.

“It really is a matter of priorities,” said Alleyne. “Are we going to take care of vulnerable people, especially the ones on the front lines?”