CHARLESTON, West Virginia — In the back of St. John’s Episcopal Church, one highway exit down from the golden dome of West Virginia’s Capitol, is a soup kitchen. Anyone can eat there, whether they’re experiencing homelessness or not, and hear about life on the streets and under local bridges.

“Oh, there is police harassment, they take your things,” said Sue Bob White, 53, while sitting at a table in front of a baked chicken lunch in a styrofoam to-go box. A bit of a celebrity from a 2009 documentary on hard living in rural West Virginia, she switched from lamenting a tent lost in a police sweep of an encampment to plans to sell clothes online. “Everyone else is getting rich off me on TikTok, after all.”

White was at the Manna Meal lunchroom with about two dozen other people who needed a meal. People come and go, some missing limbs or in wheelchairs, going outside to smoke, or grab a meal and hurry to a shelter blocks away that briefly offers a chance to shower.

Less than a mile away, a trial is ongoing between three pharmaceutical companies and the state, which alleges that the firms used deceptive advertising two decades ago to hook people on pain pills, starting an opioid crisis that is now the leading cause of drug overdoses nationwide. Here, many of the people on the other end of that story are having lunch behind St. John’s.

“There’s just a lack of hope,” said Donna, a 49-year-old woman sitting next to White. “That’s the real reason most people are here.”

No longer homeless and living in a small apartment a few blocks away with the help of an assistance program, she asked that her last name not be used for fear of harassment. She has spent nine months working on her recovery from years of using heroin and living outside.

“Something happened to them all, and broke their heart, to bring them here,” she said of the soup kitchen clients. “People aren’t here for no reason.”

“I’m done with heroin,” she added. “You get caught up in the street, picking trash, just thinking where you can find a way to get heroin. That’s all you think.”

As the meals end, clients are sent away to walk on the streets of this city of 48,000, home to what the CDC has called one of the “most concerning” HIV outbreaks in the US.

“There’s just a lot of swirling issues that kind of bring an epicenter of hurt to the city,” said Traci Strickland, executive director of the Kanawha Valley Collective in Charleston, a homelessness services provider.

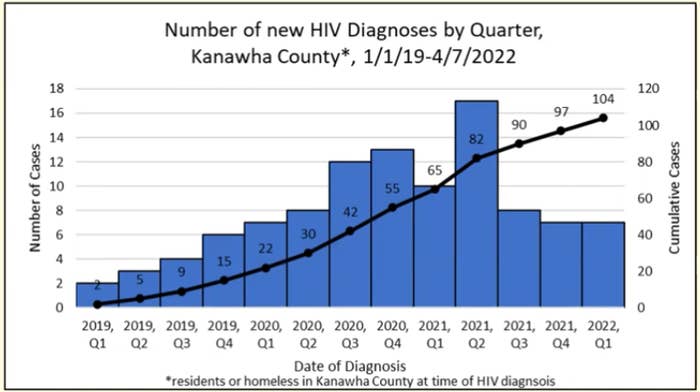

Since 2019, there have been 104 HIV cases diagnosed in Kanawha County, according to the state’s public health bureau. Most of the cases were people who use injection drugs, mostly heroin and methamphetamines, according to a January report from the CDC that also found that of 85 of them who were interviewed, 86% had hepatitis. In 2020, 207 people died from overdoses in Kanawha County, which has one of the highest overdose death rates in a state that already has the highest overdose death rate in the US.

“We have an issue with people experiencing homelessness,” Strickland said. State rules for getting mental health treatment for unhoused people who won’t, or can’t, consent to getting help have become almost impossible to work through, she added. And the city lacks a team to help people once they are housed to stay that way, which sends them back under a bridge.

“The first way to get people housed is to show them you give a shit,” Strickland said. “Like point-blank, show somebody cares, because a lot of people don’t think anybody cares. I hear that a lot here. Actually, everywhere.”

The city’s battles over homelessness, HIV, needles, and overdoses have made headlines, but they mirror those seen everywhere from Boston to San Francisco, from New York to New Orleans. These problems are uniquely concentrated in Charleston, which makes it a laboratory for the politics of homelessness, drug use, and overdose deaths.

“We are the capital of pain,” said Joe Solomon, one of the heads of the nonprofit SOAR, which, until it was outlawed last summer, ran a needle exchange on the west side of Charleston. Now, he and nine others, activists and public health experts who support harm reduction measures like needle exchanges, are running for City Council.

He recently sat across the street from St. John’s, looking at a fenced-off space where a building had burned down that once housed a homeless services provider called Covenant House.

The fire had started among tents, where people without housing had camped in January, the Charleston Gazette-Mail reported. The city only opened warming centers when the temperature dropped below 15 degrees this winter, and it was reportedly around 21 degrees when the fire ignited.

“You’d think below freezing would be good enough,” Solomon said.

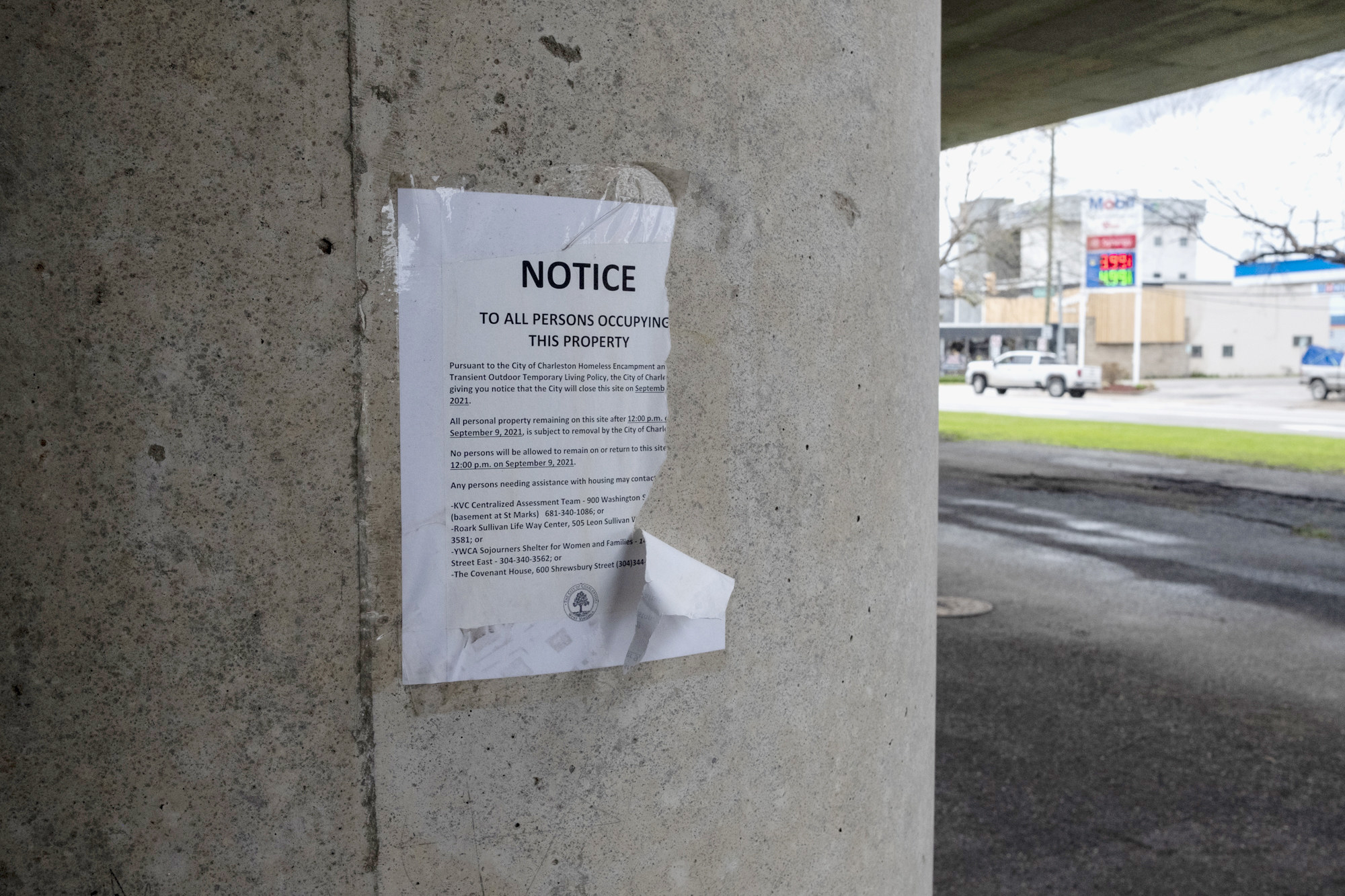

He and a few other candidates spent four days in April living among the city’s unhoused population — sleeping under bridges, eating at the soup kitchen, and hurrying to shelters — to protest recent police “sweeps” of encampments. (Charleston police officials declined to answer questions about this complaint from BuzzFeed News.)

“I’ve only been out for a few days, and it just takes so much out of you,” Solomon said. “You don’t know where to get clean or if you’ll miss a meal if you don’t hurry. Or get harassed. It’s miserable. There’s no safe place to go. You can’t really sleep.”

The CDC report flatly notes that Charleston’s HIV outbreak came after the city ended its own needle exchange in 2018, and then last year, along with the state, outlawed SOAR’s. People, “reported reusing or sharing syringes, mainly because of limited access to sterile syringes after [needle exchange] closures,” the report states. What was needed was more “low-barrier” needle exchanges to reverse the city’s HIV outbreak, the CDC team concluded last summer.

The Politics of Homelessness

It’s tempting to see the political fight in 2018 that shut down Charleston’s needle exchange as the start of a larger battle over homelessness, former City Council member Andy Richardson said. The city’s mayor at that time turned the site into the center of controversy, denouncing the program on his daily radio show as promoting illicit drug use, and pushed to overturn the law that allowed it to operate.

Often described as a victim of its own success, the downtown facility saw hundreds of visitors during the two days a week it was open, giving unmistakable visibility to the city’s drug use problem and creating a target to blame for needle litter, a signature complaint among opponents.

The 2018 shutdown of the city’s exchange led to the start of SOAR, which tried to fly under the radar with biweekly needle exchanges that were eventually held in a church parking lot. Local news reports led to a police investigation, which stalled when it was determined that SOAR wasn’t breaking the law. That finding eventually led to a state law in 2021 that outlawed the exchange and shut others across West Virginia.

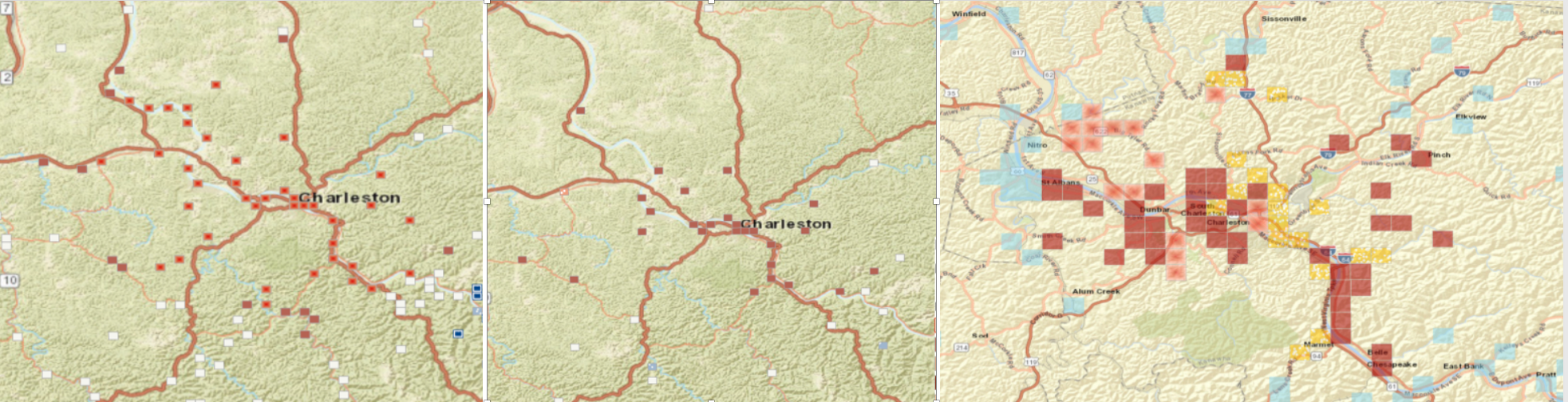

The decisions fly in the face of not only the HIV outbreak in Kanawha County, which, according to Mountain State Spotlight, now appears to have spread to rural counties in West Virginia, but also in light of increases in hepatitis and heart inflammations, endocarditis, that are caused by reusing needles. Needle exchanges usually cut rates of these diseases by half, the CDC has found. And a 2021 study of people who inject drugs in West Virginia found those who used the exchanges were less likely to initiate other people into using injection drugs.

“It’s completely devastating,” said Charleston Area Medical Center medical geographer Frank Annie, who is also running for City Council, driven by his own research showing hot spots of all three problems around Charleston. “People need to understand these are human beings, and what happens to them affects everyone.”

A Republican, he points to a study that found letting infectious heart disease spread in the community cost his hospital $13 million from 2008 to 2015.

“Even if you don’t care about the moral side of letting people get sick, the expense of letting it happen is terrible,” he said.

Science by itself won’t make changes, he realized, which is why he is running for one of 26 seats on the City Council. Primary voting will take place on May 10.

“In a more liberal harm reduction world, we’d likely try to reduce needle-related health problems,” said Richardson, the former City Council member. But on the other side, small business owners trying to restart after the pandemic see people living on the street who use drugs sleeping in the doors of their shops, public defecation and urination, and behavior that scares customers. The Fire Department has also had to deal with squatters in abandoned houses trying to stay warm by starting fires.

“On the left, the perspective is we have to help these people,” Richardson said. “On the right, the homeless and their conduct make Charleston unsafe.”

The reality is the two sides have to meet in the middle to find solutions, he added, because the problem is bigger than the city. He noted last year that Charleston’s mayor, Democrat Amy Goodwin, wrote a letter asking the state’s Republican-majority legislature to hold a special session to address substance abuse, homelessness, and mental health problems. The state ranks 30th in the country for access to mental health care, despite all its problems, the letter noted. “This is a serious issue affecting cities throughout West Virginia and requiring a coordinated, comprehensive statewide approach,” Goodwin wrote.

She was rebuffed by Gov. Jim Justice, a Republican coal mine owner who called her “Amy, baby,” and told her to “clean her own house” before asking the state to help. “Even the homeless people are out in front of my house,” Justice said. “Right here at the mansion.”

The problem is bigger than the state or its mansion. On Monday, Tennessee’s legislature voted to make sleeping under a public bridge or overpass, or on public property, a misdemeanor. The vote came a week after a Tennessee state senator said unhoused people should emulate Adolf Hitler as an example of someone who once experienced homelessness and then went on to end up “in the history books.”

TN Senator says Hitler made something of himself after being homeless & you can too. I’m going to have to apologize to the universe for this guy. Hey @MeidasTouch not a single day passes without TN GOP embarrassing the hell out of our state.😬 @meiselasb @meidasjordy @BMeiselas

In March, New York City Mayor Eric Adams had 238 homeless encampments removed after promising to put an end to people sleeping on the subway in two weeks. The drive led to only five people moving into shelters, according to the New York Times. Protesting similar sweeps in Charleston was the focus of Solomon’s canvassing of the unhoused population. Unlike New York, and despite all the attention, the number of people experiencing homelessness in Charleston is actually smaller now, around 200, than it was a decade ago, when it was more than 300.

Nevertheless, they might be more visible. A drop-in center where people experiencing homelessness could stay during the day, do laundry, and take showers, closed at the start of the pandemic, and a main library remains under renovation. A building loaned by the state was used as a temporary drop-in center replacement but had limited hours, sending people outside.

All the attention on unhoused people obscures the reality that many of the people at Manna Meal are not experiencing homelessness, but are like Donna, in tenuous housing and perhaps trying to recover from a substance use disorder. Or they just have a low-paying job and need to keep from going hungry.

“Not everybody who quote-unquote ‘looks homeless’ is experiencing homelessness,” Strickland said. “There is a belief that everybody with a bike and a backpack is homeless.”

“A lot of the people that you see are experiencing homelessness are harder to serve,” she added. They have more severe mental health issues, stronger substance use disorders, and more intense physical health issues. They are more likely to wander the streets, or nod off on church steps, or yell, she said. “They need more support, and that makes them more visible.”

Those perceptions drive some of the complaints. Charleston has two shelters for men that have about 135 beds and on any given night they have 60 empty beds. (Some people at Manna Meal complained they are dangerous and have bedbugs.) Another shelter for women, single mothers, and intact families has 76 beds and is usually full every night.

“There are a lot of women we see experiencing unsheltered homelessness,” Strickland said. “The reason they are not in shelters is because of mental health issues, I would say, pretty consistently.”

A Pandemic and an HIV Outbreak

The coronavirus pandemic arrived in Charleston just as signs of the HIV epidemic were being picked up by SOAR and in local emergency rooms. The ensuing scramble to fight a deadly pandemic hobbled testing people who use injection drugs for other diseases, said Christine Teague, director of the Charleston Area Medical Center's Ryan White HIV Program.

The new numbers were down this winter, but so was testing, as fewer people came to emergency rooms or test sites. “People hunkered down during COVID,” Teague said.

This month, the county’s HIV task force met to restart many of its testing efforts, and discuss its population with HIV. Most of them are adults 40 or younger, and just over half are unhoused. Almost all of them, 93%, also have hepatitis. With repairs, the county hopes to send a mobile testing van out twice a week and has hired a new disease investigator.

With SOAR prohibited from running a needle exchange, a more restrictive one has opened on the west side of the city, where the nonprofit once worked from a church parking lot. Treating hepatitis C costs the county $25,000 a person, while a new needle costs 50 cents. SOAR still distributes the overdose-reversing drug, naloxone, and has tripled the number of the city’s needle disposal sites in the last six months (by adding two boxes), helping dispose of 50,000 needles in that time.

“The next few months will tell the tale,” Teague said of whether the HIV outbreak has continued to grow under the surface during the pandemic. “Charleston needs ongoing disease testing, and innovative ways to deal with this, certainly, like everywhere else.”

Asked about the complaints about sweeps and too-little attention to unhoused people, Goodwin, Charleston’s mayor, pointed to the city’s Coordinated Action Response Effort office that she started in 2019.

“The truth is — there is not a simple solution,” she said in a statement. “Anyone who tells you otherwise — or offers a quick fix — simply does not understand or is not being honest.”

The statement also notes that the city must also contend with those “who are simply here in our city to break laws and take advantage of our generosity and good graces.”

Charleston’s crime rate is worse than in Baltimore, according to Neighborhood Scout, largely due to property crime.

The city does have a Quick Response Team that connects people to housing, mental health, and substance use treatment, which according to Goodwin has helped hundreds of people. A representative of the program was recently in the parking lot at Manna Meal at lunchtime, but so was a police officer leaning against a cruiser and watching the crowd.

“There’s the two sides of the city,” Solomon said. “One side wants to help, and the other side, well, what does that say?”

The CARE director stepped down in October, he noted, which can’t make the response team’s jobs easier. “These are some of the hardest working folks in the city. Truly,” he said.

The city has recommended the council accept a proposed $1 million plan for a new drop-in shelter for people experiencing homelessness as part of $37 million in pandemic relief spending. But the proposal drew complaints from nearby business owners.

Essentially, the rest of the state of West Virginia has outsourced its failure to help people to cities like Charleston, Goodwin said in her statement to BuzzFeed News.

“We are here because of decades of disregard when it comes to effectively dealing with mental health, substance use, and homelessness,” Goodwin said. “Now, cities and local service agencies across the country are dealing with the fallout — on their own and without the necessary resources and support. We need fundamental change at every level.”

City Hall Protest

On his last night of sleeping under bridges, Solomon and several of his fellow candidates from the “Charleston Can’t Wait” slate joined a group of unhoused people in front of City Hall to protest sweeps of homeless encampments. They set up a tent on the steps with “Ban the Sweeps” painted on one side and took their turns speaking.

“Someone out there showed me kindness and love, and that is what changed my life,” said Sheena Griffith, who formerly was unhoused and is now a recovery counselor.

“Imagine having a medical condition, a mental illness, a substance use disorder, and only being allowed to shelter in the evening, being made to walk the streets during the day, being criminalized for being on the street,” Griffith added. “You probably worked a long time to get that tent, or tarp, just for it to get cut up, and have you look down on me like you are something better, when you are just one bad decision away from me.”

The protest ended with a dinner of chicken curry and a reminder to vote for the candidates trying to shift the balance on the City Council toward harm reduction.

The 10 candidates running on a harm reduction platform are unlikely to all get elected or radically change the city’s 26-member council, said Richardson, the former council member. “These are activists,” he said, not politicians.

Pressure from the more liberal wing of the Democratic Party on the mayor might instead help Republican candidates who are outright opposed to harm reduction in the general election this fall, he added.

“There’s a balancing act here to getting things done,” Richardson said.

For Solomon, who spent the night under another bridge after the City Hall protest, the balancing act has swung too far the wrong way. In the last 14 months, the City Council has debated bills to ban people from loitering at downtown intersections or camping in public spaces. A new downtown plaza has benches you can't sleep on.

The choice is either go “back to the shadows” or shake things up, he said. “The status quo condones too much harm.”