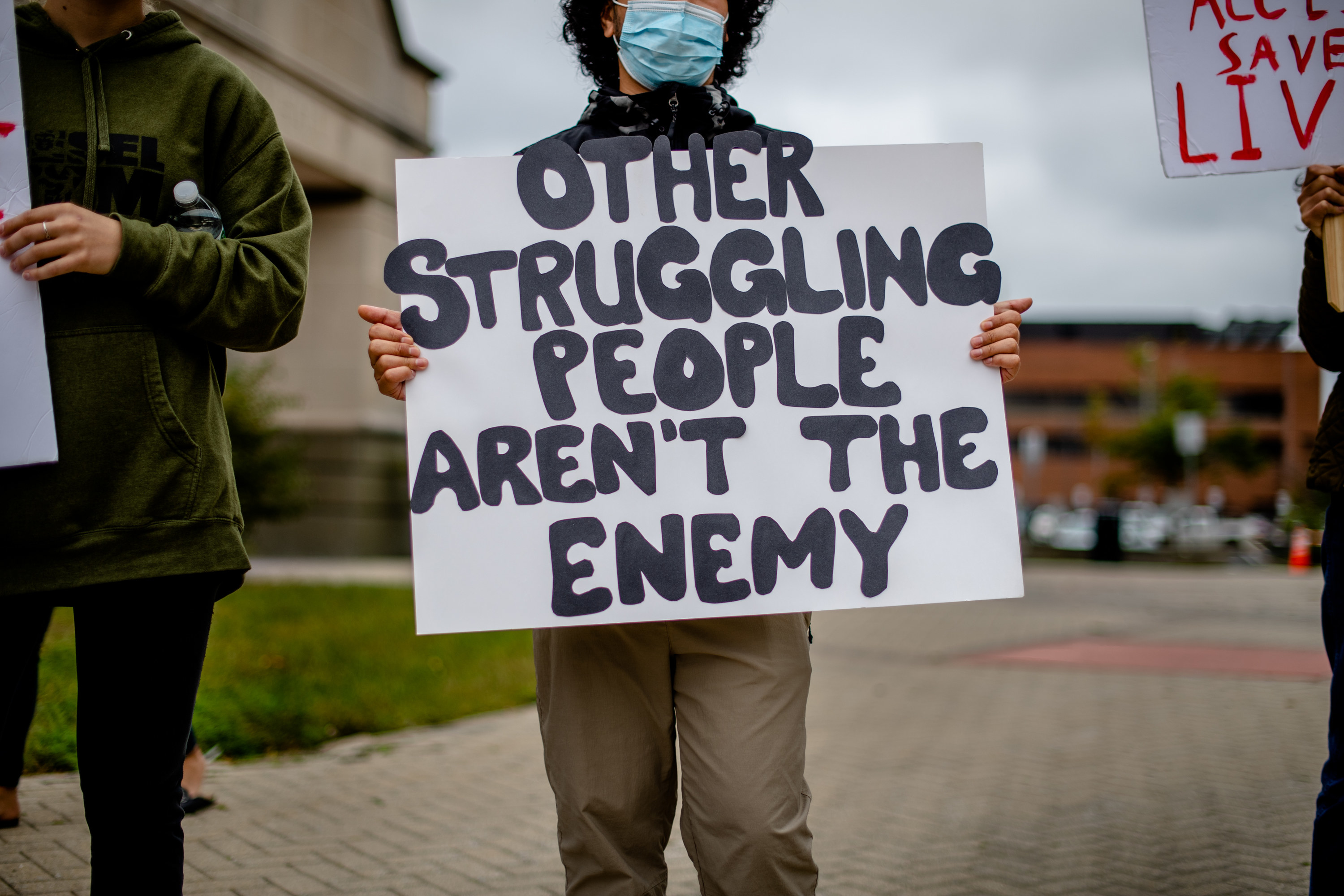

ATLANTIC CITY — On streets made famous by the board game Monopoly, protesters gathered outside city hall, just a few blocks inland from the city’s luxury casinos and famed boardwalk.

The Oct. 6 vigil and march was the last of weekly protests that had been taking place since Atlantic City voted in July to close its only needle exchange program, which has operated for 14 years and serves 1,200 people a year.

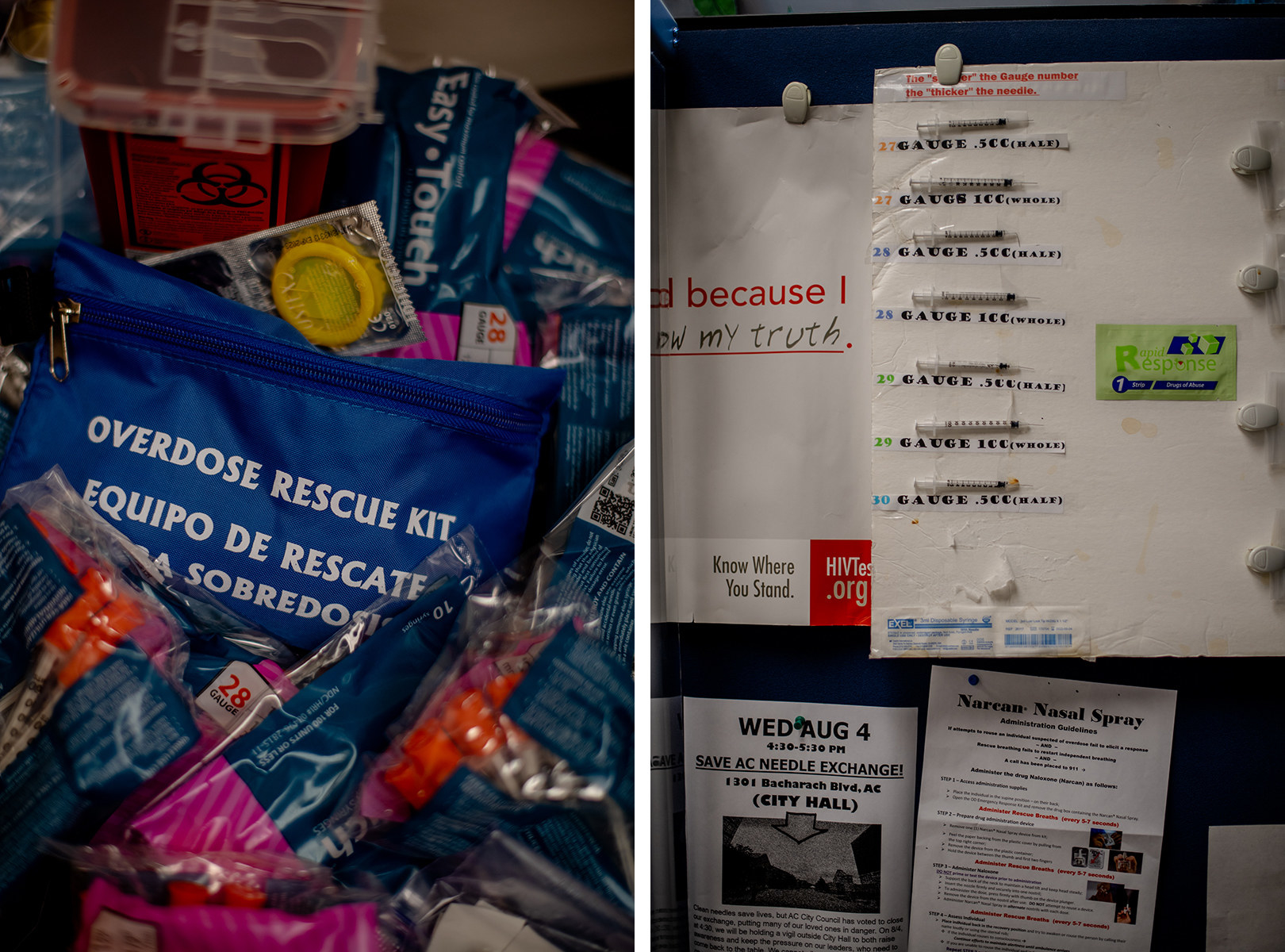

Along with new needles, the South Jersey AIDS Alliance/Oasis Drop In Center, or Oasis for short, provides the overdose-reversing drug naloxone, wound care, treatment for drug dependence, and HIV screening, which started after the city’s public health department stopped HIV tests in 2015.

“I needed to go to survive,” said Darlene McCormick at the vigil. She is a onetime client of Oasis, which is New Jersey’s largest and oldest needle exchange. “It’s about survival. This is our life and death. It’s not a joke.

“Oasis is a place that I went to, okay, and the people welcomed me, they helped me,” McCormick said.

In July, Atlantic City lawmakers voted 7–2 to close the city’s needle exchange. They did so against the advice of their own health director, and the fight is still playing out in the city council, on the streets, and now in the courtroom.

The closure, held off by an AIDS Alliance lawsuit until at least Nov. 12 and possibly by a change to state law, is only the latest in a flurry of attacks on needle exchanges nationwide, including those in Indiana, West Virginia, and California.

That’s despite a rise in HIV outbreaks among people who use injection drugs, which have been linked to shared needles, and a 29.4% increase in overdoses nationwide last year that killed more than 93,000 people. If Oasis closes, the nearest needle exchange would be in Camden, about an hour away by car.

“Here in Atlantic City, there’s a high level of people living here that are HIV positive, and about 45% of the people who have tested positive, have reported injection drug use as potential transmission,” South Jersey AIDS Alliance CEO Carol Harney said. “If they close us down, there will be an outbreak here — that’s my biggest fear.”

The city’s public health director, Wilson Washington, a veteran of the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, opposed the closure vote at the July meeting, citing the risks of an HIV or hepatitis outbreak.

Following the vote, Washington resigned from the city’s health agency later this summer, according to city spokesperson Rebekah Mena, who did not provide an explanation for his resignation. Wilson held the position for a little over a year and the city started advertising for his replacement this month.

Atlantic City was once at the forefront of establishing needle exchanges in New Jersey. In 2004, when 1 in 40 people in the city had HIV, the city council voted 7–1 to permit a needle exchange despite opposition from the state’s attorney general.

Two years later, after a court case and a new state law that permitted exchanges, Oasis added needle exchange to its services. The center originally offered pregnancy care for the disadvantaged, and that’s still a focus. However, since the start of the needle exchange, the HIV infection rate among people who use injection drugs in Atlantic City has dropped 91%.

“We really saw it as a pilot effort then, that would lead to many more,” New Jersey state Sen. Joseph Vitale told BuzzFeed News. The law gave city councils the authority to permit exchanges, not county health agencies, a compromise that helped pass the law at a time when cities were fighting the state to get them, he said.

“I’m surprised we are still fighting over this,” Vitale said. Evidence shows that needle exchanges reduce HIV and hepatitis, typically cutting local disease rates in half. The CDC estimates needle exchange clients are five times more likely to enter drug treatment and three times more likely to stop using drugs.

Vitale has cosponsored a bill that would allow the state health department to open needle exchanges across New Jersey. The state of 9 million people now has only seven needle exchanges. (Kentucky, a state with half that population, has almost 60.) “I don’t know how many exchanges we need, maybe one in every county, or two, if it is an especially large county,” Vitale said. “We don’t need fewer.”

At Oasis, a brick storefront resembling an insurance agency, clients are buzzed in singly on the three days a week the needle exchange is open. The exchange sees around 25 people on a normal day. Since the pandemic started, the counselors can only see two people at a time, and everyone wears a mask.

Despite years of hearing about tough circumstances from clients, “I cannot honestly say that I’ve heard it all. I mean, you’re gonna get some sad stories,” said Mark Hewett, one of the counselors who interviews people as they exchange needles: old ones for new ones. “We get to know them... We tell them, ‘There’s options, we can help.’”

Along with HIV and hepatitis testing, Oasis’s clients are asked about what drugs they are using. They are offered the overdose-reversing drug naloxone, test strips that can detect the powerful drug fentanyl, and coaching on safe sex and how to safely dispose of syringes. There is nursing care, typically for abscesses that can form at needle wounds. People who test positive for HIV are walked to a health center for treatment a block away.

The exchange also offers medication-assisted treatment for dependence on opioid drugs, including heroin and illicit fentanyl, which is the drug causing record numbers of fatal overdoses nationwide. Like many cities, heroin use in Atlantic City has largely been replaced by the even more dangerous drug fentanyl, which is roughly 50 times more potent than heroin.

“You cannot do this work by telemedicine,” Hewett said, referring to the need to discuss drug use, test for sexually transmitted infections, and exchange needles. “You have to do this face to face with people.”

The most common and hidden public health service that Oasis provides to Atlantic City is screening people most at risk for HIV and other diseases that can be transmitted sexually and/or via intravenous drug use.

Some people who visit the clinic are involved in sex work and cater to the tourists who come to the city to gamble, attend bachelor parties, or vacation at the beach. Catching those cases and getting people into treatment not only helps the most disadvantaged, but also stops outbreaks that would devastate the oceanside resort town.

“It seems obvious, but there are a number of tourists that are seeing our commercial sex workers,” said Babette Richter, a registered nurse for the Access to Reproductive Care and HIV Services program at Oasis. “And then they come to see me for an STD test, because they saw this girl at the hotel this week.”

Janet Duran of the New Jersey Red Umbrella Alliance, a sex workers rights group, held a “Save Oasis!” sign at the vigil.

“I would say, at least 80 to 90% of our clients are always looking for how to score some drugs,” Duran said. In June, two tourists from the United Kingdom were found dead of overdoses in their Bally’s Casino hotel room, and a local man who allegedly provided them the drugs was charged with homicide and drug distribution.

“It’s rampant in the casinos,” Duran said. “You cannot separate what happens in those hotel rooms and what happens at night on the street. You can pretend [it doesn’t], but it all ends up here,” she said, pointing toward Oasis.

But for the Atlantic City council members who voted to end the needle exchange, Oasis is a problem, not a solution.

According to council president George Tibbitt, it’s the source of the needles he said he found in a park ahead of the July decision. Tibbitt did not reply to a BuzzFeed News request for comment on the current lawsuit regarding Oasis.

However, at the council meeting where they voted to close the needle exchange, he and other opponents of Oasis argued that the exchange acts as a magnet to pull people who use intravenous drugs to Atlantic City, filling the boardwalk at night with individuals begging for change, fighting, and driving away tourists. Other towns in New Jersey should open their own needle exchanges instead of them ending up in Atlantic City, they argued.

“I just want to show you something,” Tibbitt said, holding up a plastic container filled with needles he said were collected from a city skateboarding park. “Is that fair to our children?” he asked. “Is that fair to our residents?”

Oasis, however, is a needle exchange that aims for a one-to-one exchange of new needles for old ones, receiving almost as many used ones as it hands out. Providing people as many new needles as they need is the most effective way to stop HIV outbreaks, according to the CDC, but the one-for-one policy is one of New Jersey’s guidelines for such operations.

On their first visit, if a client doesn’t have any old needles to exchange, they get just one new one, Hewett said.

Down an alley near the needle exchange is a rooming house, its front porch filled with refuse and bags of trash spilling open in the side yard. “If the needle exchange closes, people will be pulling old needles out of those trash bags,” said Lance McCormick, an older man who identifies himself as an Oasis client. “I’ve seen it happen before. It will just happen again.”

When people use an opioid, such as heroin or fentanyl, the body inevitably becomes dependent on the drug with long-term use. Without it, people go into withdrawal, risking symptoms such as shaking, chills, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, all accompanied by a deep depression. The risk from a used needle pales in comparison to the threat of withdrawal for some people who use injection drugs, as many also have mental illnesses as well as a drug dependence.

“Anyone who thinks people will just stop using if they close the exchange is crazy,” McCormick said. “That’s not how it works.”

“Hey Ho, Hey Hey. Oasis is here to stay,” the marchers chanted along Atlantic Avenue, which in the game Monopoly is a Yellow Card property. The modern game’s locations and their rents embody the reality of the housing market in the 1930s version of Atlantic City and “reflect a bitter legacy of racism and residential segregation,” the Atlantic’s Mary Pilon wrote in a February history of the board game. In those days, Atlantic Avenue and other nearby streets named in the game were relatively high-rent districts.

No more. On today’s far less glamorous streets, the marchers for Oasis advanced past check-cashing storefronts, massage parlors, rooming houses, and take-out joints. They marched past Pennsylvania Avenue, onto North Carolina Avenue, and back along Pacific Avenue. Blocks away loomed the Hard Rock Hotel and Casino and the Club Wyndham Skyline Tower, fronting the storied boardwalk.

“Atlantic City is a First-World facade covering over the Third-World truth,” said city council Vice President Mo Delgado, one of the two council members who voted in July to keep Oasis open. “Too often the casino industry calls the shots here. I think, they think, the exchange causes bad publicity for the city. They don’t see the people who will be hurt if it closes.”

Like Monopoly, the battle over Oasis is also a struggle for real estate. The needle exchange is located on Tennessee Avenue, two blocks inland from the famed boardwalk and the Ripley’s Believe It Or Not! Museum. A decade ago, Atlantic City declared the area the tourism district.

Two years ago, the city tried to drive out “rundown” rooming houses on that street, according to the Press of Atlantic City, to make room for yoga studios, beer halls, and a chocolate shop. The needle exchange did attempt to move out of the tourism district, Harney said. They planned to relocate farther from the beach and move next to a homeless shelter and a drug treatment center, but the move was blocked by the city earlier this year.

“We were all ready to move,” Harney said. “It was just a great solution. It would have created a little hub and it was behind the train station, out of the way but still in the city.”

For now, Oasis is still open on Tennessee Avenue. It will be open, at least until the Nov. 12 court date when the lawsuit filed by the South Jersey AIDS Alliance and three clinic clients will be heard in Atlantic County Superior Court.

As the march ended and participants took photos, a young man wandered through the crowd, dressed in a coat despite the warm day. He was clearly disoriented and asked for spare change. Instead, he was offered food and the overdose-reversing drug naloxone, which he eagerly took before walking down Tennessee Avenue, deeper into town. He was promised more help if he came back tomorrow to the still-open, for now, exchange.

“You know, we really have done our best to kind of be quiet, do our thing and be out of the way. And clearly that didn’t work,” Harney said. “Now we have really changed that. We’re talking to a lot more people.” ●