A company that charges people upwards of 50% to transfer money to friends or relatives who are in prison is under scrutiny by federal regulators and New York City officials for its financial and business practices. The news, confirmed by public records and people familiar with the matter, follows years of criticism that the company, Florida-based JPay, exploits people seeking to help their relatives behind bars afford necessities like winter clothes and prescription drugs.

The federal Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has issued a subpoena instructing the company to provide detailed information about its finances, policies and practices in connection with a probe into how it treats its customers, according to two people with direct knowledge of the inquiry. They spoke on condition of anonymity because of a bureau policy against discussing ongoing investigations.

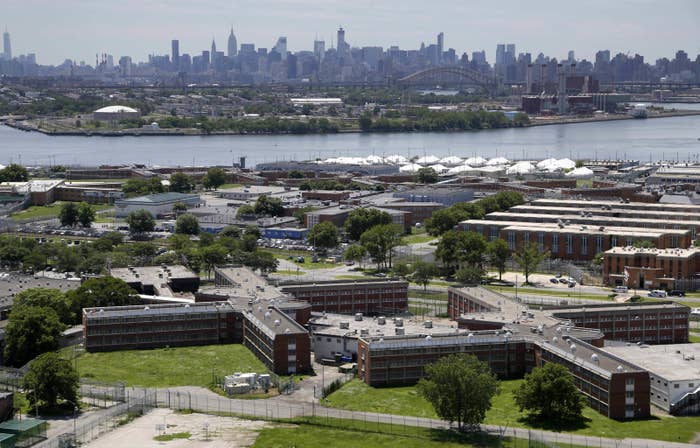

Separately, New York City’s Public Advocate has introduced legislation that would cap the money transfer fees JPay charges at Riker’s Island, the city jail complex, at $5 — less than half of the company’s current top fee. The city’s Department of Investigation, an independent watchdog agency, has joined discussions with the public advocate about JPay.

”Corporations should not be skimming off the top before the detainees even get the money from mom or dad,” Public Advocate Letitia James has said. Many people are locked up because they can’t afford other fines, fees or bail, James said, and “the system should not further penalize their family and friends” with fees that she called “basically unconscionable.”

New York State already imposes a cap of $5 on the fees, James noted, but the state’s top corrections regulator has — without public discussion — waived the limit for JPay each year since it was awarded a city contract in 2007.

A JPay spokesperson declined to comment on the federal investigation or the proposed fee cap. Reached by email in September, JPay founder and then-CEO Ryan Shapiro wrote, “If you had a bit of integrity, and were able to report accurately without lying, you might have had my assistance.” Shapiro stepped down as CEO two weeks later and was replaced by Errol Feldman, a longtime executive at the company. The company has said its fees are necessary to cover its operations.

JPay says it serves 1.9 million offenders and parolees in 34 states. That’s a hefty slice of the 2.2 million adults behind bars and 4.7 million on probation or parole in 2014, the most recent data available from the U.S. Justice Department. Aside from money transfers into prisons, JPay processes fees people on parole must pay as part of their supervised release. It also provides technology like tablet computers inmates can use for electronic messaging and music downloads, all for additional fees.

Money transfers remain JPay’s core business. The company expected to transfer more than $1 billion to inmates in 2014, according to internal projections at the time, and its customer base has grown since then. Prison agencies often pay nothing for the contracts; instead, JPay makes money through its transfer fees charged to prisoners’ families. In some cases, it has even returned some of this income to the government agencies.

Inmates are required to pay for a growing list of items they need for basic health, hygiene, and even to perform their prison jobs — things like shampoo, workboots, supplementary food and prescription copays. With prison jobs paying as little as 12 cents an hour, contributions from family and friends become necessary for inmates to afford such essentials.

A spokeswoman for the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau declined to comment; the agency has a policy against confirming or denying the existence of ongoing investigations.

However, the agency has been working with inmates’ rights advocates to collect stories about families’ experiences with JPay, including their struggles to afford its fees and delays in processing payments, according to Paul Wright, founder and executive director of the Human Rights Defense Center, which also publishes Prison Legal News.

JPay’s money transfer fees are a key revenue stream for Securus, a larger prison vendor that acquired JPay for a reported $250 million last year. Securus traditionally has relied on income from high rates charged to inmates making phone calls. As the Federal Communications Commission moved in recent years to limit what prison phone companies can charge for calls, executives have sought new ways to profit from prisoners.

Inmates and their relatives say JPay’s fees are a major hardship for poor families, especially in cases where the person behind bars was the breadwinner before being locked up.