It was freak-snowing in April in Chicago when the Fight for 15's National Organizing Committee gathered to plan the movement's biggest action yet.

Most of the workers would be in the city for just 24 hours, barely leaving the O'Hare Hyatt's conference rooms. In a marathon session there, they hammered out the logistics of a nationwide day of strikes and protests planned for this Thursday, and celebrated two huge victories: $15 minimum wage increases in both California and New York.

The organizing committee has always kept its meetings closed to the press, but BuzzFeed News got an exclusive look at the inner workings and backstory of what is now, undeniably, the most successful labor movement in recent memory.

This week, the committee will execute their biggest action yet, targeting McDonald's locations across the country and internationally.

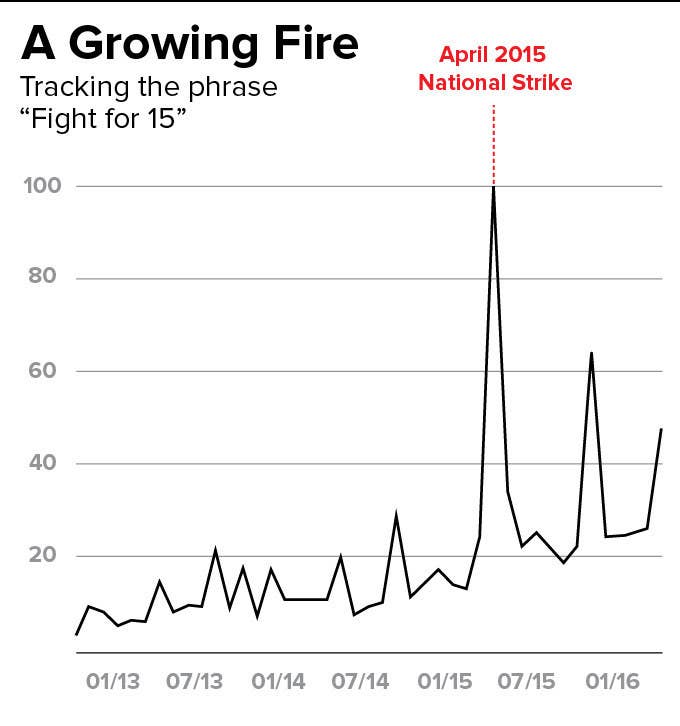

It's a return to a familiar target. Fast food workers went on strike for the first time back in November 2012 — when 200 cooks and cashiers walked out of New York City restaurants. Last April, they marched in 200 cities and stopped traffic. Thursday, they'll be on six continents. Here's how they got there, and secured higher pay for millions of Americans in the process.

Heat in fast food

Most members of the Fight for 15 organizing committee are women of color in their twenties — the youngest is 19, the eldest 58. At 24, veteran striker Naquasia LeGrand is representative. And she's represented the movement — on The Colbert Report, major news networks, and in print — from the start, as one of the first workers to risk her job by walking out in protest.

Naquasia Legrand, 24, one of the original members of the Fight for 15.

But in the summer of 2012, LeGrand was a crew member at a KFC at the intersection of Brooklyn's 9th Street and 4th Avenue, paying off student loans, when petitioners visited the store to collect workers' phone numbers for a survey about affordable housing.

When the advocates made follow-up calls to LeGrand and her co-workers "they couldn't even get to housing, because the workers would go on these tirades," remembers union organizer Kendall Fells.

The callers heard the same chorus from fast-food employees — low wages, no raises, unjustified firings, unpredictable hours, abusive managers, grill and oil burns — so many times they ditched the housing questions and immediately flagged the industry to their union funder.

“These workers are really hot. You might want to come take a look,” they reported back to management.

In labor organizing, “heat” is a measure of worker responsiveness, gauged by the frequency with which employees show up to meetings and take calls, their enthusiasm to talk to other workers, and to strike and risk their jobs. A willingness to shut down highways with their bodies and get arrested — which fast food workers have in droves — is especially fire.

The Service Employees International Union sent Fells to take a closer look. He has been on the front lines of fast-food protests ever since.

Rolling up their sleeves

At the first 2012 meeting of what would become the Fight for 15, 40 or so workers from across the major franchises — McDonald’s, Wendy’s, Burger King, Papa John’s, Domino's, KFC — showed, including LeGrand.

"Being in the room at that moment and listening to everybody's stories — it was unreal," she said. "I couldn't believe we all worked at different places."

From around the room, regardless of the company, came the same story: wage theft, off-the-clock work, and no raises. Many spoke of firings without warning; one worker was let go for eating a single chicken nugget and another for drinking water out of a medium-sized cup. Others spoke of irregular hours and managers changing schedules and shifts at the last minute.

“Lightbulbs started going off,” Fells said. “Because the conditions were consistent across all brands and all parts of the city.”

At one point, a worker who had been badly burned by a grill said his manager had told him to put butter or mustard on the wound. He lifted his shirt to show the scar, and other workers rolled up their sleeves to show similar burns on their arms.

At the second meeting, twice as many people showed. And the group landed on their signature demands: $15 an hour and a union.

A political education

There are 64 million workers who make less than $15 an hour in the United States. Many have never voted. In 2012, the fast-food workers showing up to meetings weren't especially familiar with city or state politics, Fells said, but in the time since, workers have received a crash course in civics.

"I learned more about labor rights and history from being a part of this than I did from all of school," said LeGrand, who is now well-versed in labor law, strike protections, and the workings of local, state, and federal government.

With the support of SEIU, LeGrand has met with sanitation workers who went on strike with Martin Luther King Jr. and accepted an invitation to stand beside New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo when he passed the state's wage raise. She personally handed her bullhorn over to Vermont Senator and Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders on a recent picket line.

Adriana Alvarez, 23, another member of the NOC, traveled to Rome to speak to a council of advisers to Pope Francis about McDonald's pay and working conditions. Her contribution made it into his most recent encyclical. The photo background of NOC member Terrence Wise's phone is him, his mom, and President Obama. Wise introduced the president at a Department of Labor summit late last year.

"Terrance could run for something," President Obama said as he took the podium, but Wise has said he isn't interested. After he was profiled by the New York Times for his role as a strike leader, the Burger King employee said, a vice president for the franchise flew to Kansas City and offered to buy him off. "He said he could get me more money and make me a manager within a year," Wise said. He declined. (Burger King and the Kansas City franchise did not respond to requests for comment.)

The SEIU is quick to point out that the same movement that will send thousands of people into the streets Thursday has the potential to be a get-out-the-vote machine for low-wage workers in November. The campaign has not endorsed a candidate, though Sanders has repeatedly joined their strikes and supports raising the federal minimum wage to $15. Hillary Clinton, who landed SEIU's endorsement, has called for an increase, but stops short of a nationwide $15 minimum.

Enter the minimum wage

In 2014, protesters in the Seattle suburb of SeaTac successfully pressured officials to enact the first local $15 minimum wage — soon followed by an increase in Seattle itself. Activists in Kansas City, San Francisco, and Los Angeles took up similar campaigns, and in 2015, Cuomo convened a rare Wage Board to raise pay for fast-food workers to $15. "That was a eureka moment," Fells said.

Fight for 15 chief strategist Scott Courtney, as well as Fells and NOC members, have said that shifting focus from McDonald's to the minimum wage was never part of the plan. But in targeting politicians who have the power to raise pay floors, workers effectively leapfrogged their employers to bargain collectively with lawmakers, using the power of their votes as leverage, they argue.

The same way a union-negotiated contract may result in yearly increases, workers will see their hourly wages rise incrementally under the new laws, said Fells. Plus, the wage regulations cover far more workers than just line cooks and cashiers.

"The tent is so big we’re now bringing every major industry under it," said Fells. "Whether you’re talking about retail workers, home care workers, airport attendants, or child care workers."

Since so many employers pay the legal minimum, raising that floor has resulted in more gains for more workers than the fast-food protesters imagined four years ago.

"Elected officials feel obliged"

Ruth Milkman, Distinguished Professor of Sociology at the City University of New York, sees parallels between the present and the early 20th century, when many states and cities passed the first minimum wage laws and labor protections.

"That too was an era of rampant sweatshop labor and massive inequalities," she wrote in an email to BuzzFeed News. "Today those laws are still on the books but have been successfully subverted by private sector employers — to the point that they are rarely operating in the intended manner."

Widespread contracting and the franchise system have helped insulate McDonald's and other big corporations from liability for labor conditions — while keeping tight control over many operational details. McDonald's executives have insisted that it is up to franchise owners to decide what to pay their staff. As a result, politicians and lawmakers are proving to be low-wage workers' best hope for improving their conditions, Milkman said.

Cases in point are the landmark minimum wage increases to $15 signed into law this month by Gov. Jerry Brown of California and Gov. Cuomo of New York, which will eventually raise pay for approximately 9 million people. Fast-food workers may have set out to face-off with McDonald's across the bargaining table, but their demands, stymied on one front, have led to a much broader civil rights battle.

"Public concern about the skyrocketing growth of inequality has increased to the point that elected officials feel obliged to address the issue," said Milkman. "And campaigns like the Fight for $15 offer them a way to do that."