It was the free pizza that led Andy Stern to his first union meeting, back when he was working as a welfare caseworker in the 1970’s. He rose fast through the ranks, eventually claiming one of the most powerful positions in the labor movement: President of the 2.2-million member Service Employees International Union.

Since retiring from the SEIU in 2010, he's spent his time researching the effects of technology on American jobs, and thinking about the kind of policies needed to help workers cope with the changing labor market. In his new book with Lee Kravitz, Raising the Floor, Stern argues that a universal basic income (or UBI) — a guaranteed salary for all, without work requirements — will become a necessity as automation and on-demand labor take over wider swaths of the economy.

BuzzFeed News spoke with Stern about the book, and how he joined figures as ideologically diverse as Milton Friedman, Bertrand Russell, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Richard Nixon in supporting a universal basic income. Here's an edited version of the conversation.

Based on your research, how are automation and technology hastening policies like a basic income?

I think the tipping point will be driverless trucks. It’s the largest job in 29 states. It’s 3.5 million truck drivers. Then there are 6.8 million people in auto repair, insurance, rest stops, gas stations and emergency rooms that all live off those 3.5 million people. They won’t disappear overnight, but you know business will deploy labor-saving technology before you or I debate whether we want it and wait until our next car comes.

Business is not going to wait if they can eliminate large numbers of workers. And then we’re going to have this mass problem. Let’s assume it’s two or three million people distributed all throughout the country. That will make what happened in the steel or auto industries look tiny.

I think there is going to be an elimination of jobs much larger than what we saw during the industrial revolution, and I don’t think we’re prepared. It’s very easy to say we’ll just create jobs through something like the WPA [Works Progress Administration]. I think it’s a lovely idea that’s really worth pursuing, but it’s remarkable how little research you can find on a contemporary WPA.

There’s a lot of discussion about re-building infrastructure, child care, and elder care as potential opportunities for a new jobs program.

Everyone says infrastructure and elder care. It doesn’t seem like a good works program for all the college kids, financial analysts, bookkeepers, accountants, real estate and financial agents who will be replaced. But that’s a debate we should have — how do we pay women who are currently doing child care or elder care who don’t get compensated?

Proponents for a basic income argue that it could be an answer to that question.

Judith Schulevitz wrote a great article about this. [From that piece: “The feminist argument for a U.B.I. is that it’s a way to reimburse mothers and other caregivers for the heavy lifting they now do free of charge… Notwithstanding the advent of the stay-at-home dad, it’s still mothers who do most of the invisible labor of cleaning, schlepping, scheduling and listening.”]

Do you see the fight for a minimum income as an extension of the Fight for 15 and a living minimum wage?

I think the minimum wage is a perfect solution in a 100% employer-employee, job-oriented society. But most of the job growth since 2005 has been in contingent and alternative-engagement work. So it’s like unions: when unions only apply to 6% of the workforce, it’s not enough.

There may be a tsunami coming. Right now we’re buying sump pumps, which are not going to work when Sandy or the tsunami arrives. We should own a sump pump, it’s good to have a minimum wage, but I think the Fight for 15 will have more limitations as people become less attached to an employer, such as Uber drivers, day laborers, and child care and home care workers not working for agencies.

From when I first came into the labor movement, until the late 1990’s, when more people who had been progressive anti-war-types came in, the labor movement was against raising the minimum wage.

Why was that?

If you wanted a higher wage, you joined a union. They were against universal healthcare, too. They would say, “You want healthcare? Join a union.” There was an answer to your question, and all questions had the same answer.

You write that a UBI would give workers more leverage at the negotiating table. How would that work?

I think about the UBI as a permanent strike fund, so employers can’t starve you out. Right now, to strike, you need a union to help pay people. With a UBI, more workers could collectively walk away from abusive workplaces.

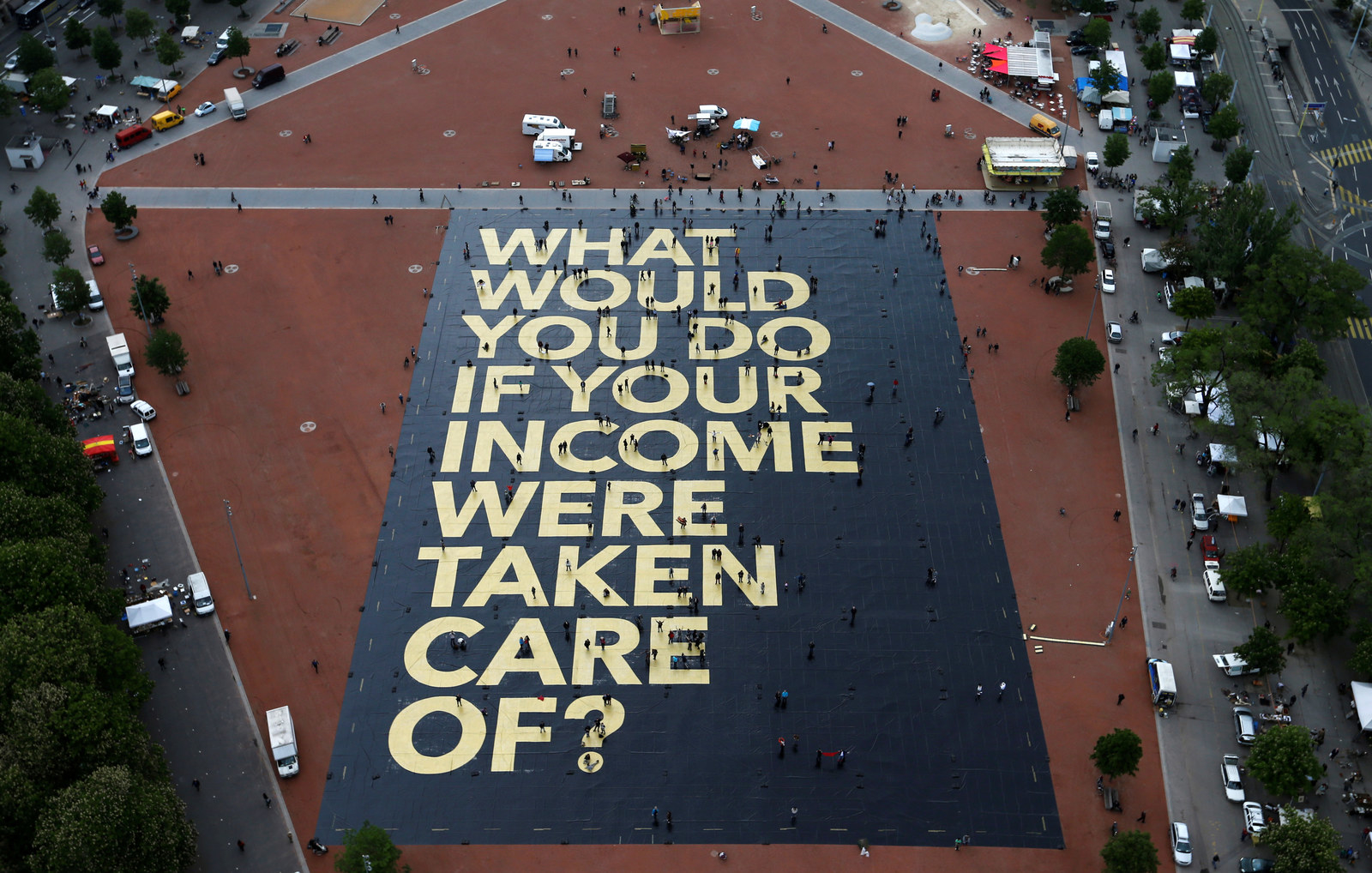

The Swiss referendum on basic income, which you mention in the book, took place last week. It failed, with 77% against and 23% in favor. What are your takeaways from the vote?

I think millennials voted for the proposal in higher numbers, which is where I think the strength of this lies. [A Swiss poll found that 41% of 18-29 year-olds believe basic income will become a reality.] And 70% of all Swiss voters, yes and no voters, think there will be another referendum in the future.

At one point in the book you write about a fundraiser, mainly attended by billionaires, where one billionaire says “the guillotine is just around the corner,” and no one laughs. They nod knowingly. Do you see inequality hastening a basic income?

There’s an economic stability question. There are a lot of wealthy people who aren’t necessarily going to be opposed to a UBI. Welfare was somewhat created after the riots to ensure people wouldn’t move out of urban areas into nice suburban areas. There are a lot of people who would pay money for stability.

After seeing Donald Trump, I think people understand that when people are hurting the way that they are, you don’t always get a rational consequence. Ask Mussolini. Ask people who took advantage of dire economic situations. I think Trump is helping people understand that this isn’t just a case of, “We’ll elect another president, and this will all be fine.” Forty-seven percent of people don’t have $400 dollars to cover an emergency expense. People don’t get how desperate people are becoming.

I think inequality could become like the Vietnam war, when households across the economic spectrum were affected by the draft. All my friends have kids who are moving back home or needing some help. Parents are beginning to realize this, which is a really important part of the book for me. People are blaming themselves and thinking that they did something wrong. All you had to do when I grew up was go to college or get a union job and you’d be okay.

When you say parents you mean parents of -

The upper middle class. Upper 20%.

Because other parents already know.

When something becomes a middle-class problem, it becomes a problem in America. When it becomes a problem for white workers, it becomes a problem in America. There’s a statistic that stands out to me — there are more people on disability now than there are who work in manufacturing.

If you watch the trends, we went from one-income families to two-income families, then the number of hours people worked decreased. Then we turned to credit cards, home equity loans, intergenerational transfers, and government programs like disability. We find other ways to cope with the fact that people aren’t making enough money. We can’t put more people to work in the family, but we can have them move in and share.

Which has long happened in poor communities and communities of color.

But now it’s a “national problem” because it’s affecting white people — like opiates. Congresspeople, those living on a congressional salary, trying to keep up two homes — their friends telling them about their kids’ problems begin to get this across. They don’t run across poor people unless they do a “visit”’ to a senior community center or a job training center. But they go to their kids’ birthday parties or their cousins’ events and everybody starts talking about this.

The thing about being rich is you can choose: you could work hard all day, or you could go home and retire at 45. Having choice is such an empowering feeling. There is nothing worse than going to a welfare worker, and I was a welfare worker. I was sitting there — 25-years-old — and I’d say, “I’m sorry. I’d love to give you the money, but you have to show me you’ve looked for three jobs, and I have to come visit your house, and you have to show me you have no other source of income.” It was so demeaning — this white kid of privilege asking these questions.

I don’t think people understand - everyone should have to read $2.00 A Day, Evicted, Nickel and Dimed, books about getting by in America. What’s sad is there’s absolutely no question that Sanders and Trump are fueled by the pain and the anger that people are going through, and everyone wants to talk about the pain and the anger, but economists and the media say things like, “this is the 42nd month in a row there’s job growth.”

I get so frustrated when people want to debate things like productivity numbers. I say, “Do you know the future? Because if you do, let’s go work the stock market.” The storm’s coming. Do we have to wait until it hits? It’s the privilege of privilege — which is that you can be wrong and experience no consequences.