Last year, high school teacher Mallory Heath assigned her humanities students an essay to consider a basic, personal question: Who am I?

It was the 30-year-old’s fifth year teaching at Basha High School in Chandler, Arizona, her hometown. When she sat down to answer the question herself, she had an epiphany, the kind of lightbulb moment she always hopes to inspire in class.

“Without teaching, I didn’t know who I was,” she told BuzzFeed News.

Also apparent: All that she was pouring into work, which was all of herself, really, had left her $18,000 below the national median household income, with little room to advance.

Her essay morphed into an open letter to Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey, exposing Heath’s frustration, anger, and despair over education funding.

“Doug. I’m college fucking educated. I can’t even hit a middle class salary? When you slashed budgets across Arizona, I want to know if it was with a smile,” she wrote.

“I am more than enraged. I am seeing red. When I think about the inequality in teaching, and the apathy associated with it, it makes me want to scream until my voice is gone.”

She posted it online, where it spread on social media and drew the attention of local news outlets. Just over a year later, in spite of the solidarity she inspired, Heath tearfully submitted her letter of resignation on March 30. Her 11th- and 12th-grade students and staff know she still loves teaching, but she’s told them she can’t stay.

“I don’t even make a living wage,” she said. “I don’t make enough money to cover my bills.”

Education advocates have for years sounded the alarm of a teacher shortage as baby boomers retire, midlevel teachers burn out, and university students choose other higher-paying professions. And now more than ever, teachers around the country, via strikes, protests, and fiery social media posts, are announcing they’re at a breaking point. Salary freezes and tight budgets that came with the recession haven’t rebounded along with the economy. Adjusted for inflation, the average Arizona high school teacher earned 10% less in 2016 than in 2001. Teachers like Heath, even with their passion for the job, can’t afford to wait any longer for a raise.

The number of teachers leaving the profession has been going up over the last decade, and the rate is twice of what’s typical in countries like Canada or Australia. Given that US teachers make about 30% less than other college graduates, it’s understandable, said Linda Darling-Hammond, president of the Learning Policy Institute.

“We were kind of sold a different dream as to what teaching looked like.”

“These strikes are really coming out of a deep desperation, often from people who want to stay in the profession, but they can’t,” she said. “They can’t feed their families if they stay in teaching.”

And when teachers leave, districts are left scrambling to fill positions. Often, they’re forced to hire people who are inexperienced, lack particular subject-matter prowess, or who don’t have a teaching credential at all. It’s bad not just for students, Darling-Hammond said, but for the country as a whole.

“If you don’t have good teachers, you can’t have a strong education system,” she said. “If you don’t have a strong education system in the 21st century, you can’t have a strong society and economy, because this is a knowledge-based economy.”

Heath graduated from Arizona State University’s education program in 2012. Originally a psychology major, she knew that more than anything she wanted to help kids.

“It just kind of dawned on me that reading and writing had been a safe haven for me when I was growing up,” she said. “I realized I could probably help a lot more kids on a grander scale if I became an English teacher instead.”

She powered through the English courses, and by graduation, earned a 4.13 GPA within the teachers college. Student teaching felt like magic. From her first moments at Basha High School, she was struck by the caring staff and sense of family. When the school offered her a full-time job, she was thrilled — it was the only place she’d really wanted to work.

Her starting salary was $35,800, which sounded like decent money to Heath. Then her first paycheck arrived: $945. It was a rude awakening after working 60-hour weeks, but she remained optimistic. Older teachers had told her if she got through the first few difficult years, she could achieve a comfortable, middle-class life.

It was the first year that the Chandler Unified School District had eased a seven-year salary freeze instituted to avoid layoffs after the recession, but nationally, education funding was still almost 6% less than before 2008, and in Arizona, the situation was more extreme. The state had slashed education funding during the downturn, then state leaders had cut taxes. A sliding pay scale and career ladders were gone. A $10,000 salary bump for obtaining a master’s degree was reduced to $1,000. Even teachers who had started working only a few years earlier had a different experience than Heath and her classmates, who couldn’t count on raises to match inflation.

“We were kind of sold a different dream as to what teaching looked like,” she said.

Forty-two percent of Arizona teachers hired in 2013 were no longer in public schools by 2016. Heath was determined to beat those odds. She’d wake at 5 a.m., often listen to educational podcasts while driving to school, then grade papers when she got home 12 hours later. She never stopped thinking of “my kids,” as she still calls the students, and sometimes she’d hear from them years later when they let her know she’d helped them endure the painful years of adolescence. So in a sense, her hard work was paying off.

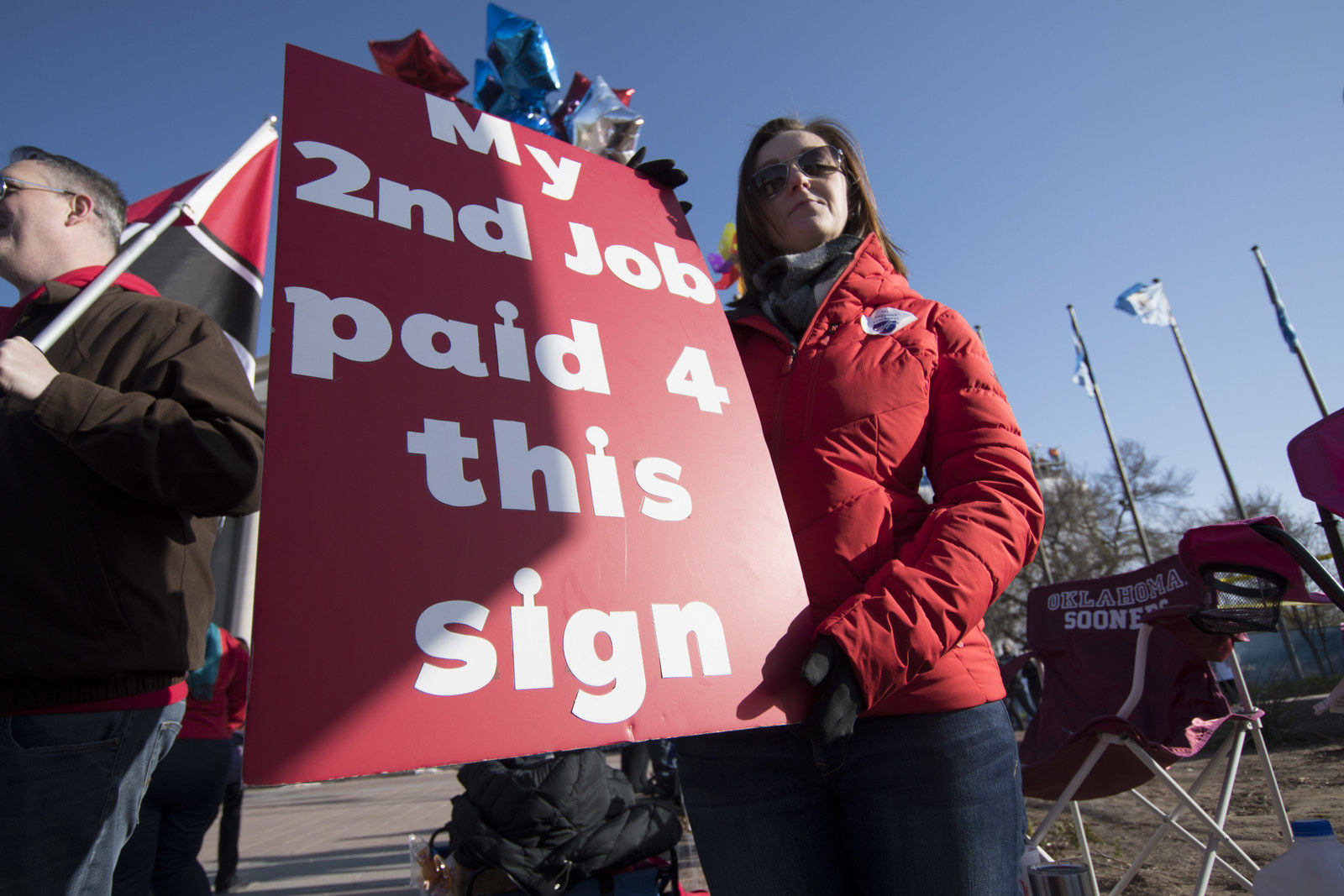

She didn’t have student loans. She wasn’t financially responsible for a family. Yet with a college degree, six years of experience, and professional recognition, she couldn’t earn enough to support herself without taking on a roommate or, like 16% of teachers, a second job. In Heath’s case, that second job was waiting tables at a steakhouse, but after the first year and a half of juggling it with teaching, she gave it up.

When her tires wore out, she found herself calculating whether the bill or a blowout would be worse.

Her teaching salary peaked at $42,812 a year, but Heath couldn’t keep her head above water. Her basic bills — her town house’s $889 mortgage, insurance, gas, groceries, and utilities — totaled $2,500 a month. After taxes and deductions, she was making $2,200, leaving her $300 in the hole.

Every purchase, down to items like Band-Aids, was scrutinized for potential pennies of savings. When her tires wore out, she found herself calculating whether the bill or a blowout would be worse.

“When I hear that something needs to be replaced, it’s a punch in a stomach,” she said. “I have a pair of glasses that I’ve had since I was 19 that I just glue back together because I can’t afford to buy a new pair of glasses.”

Arizona has long occupied the bottom of rankings for teacher pay and dollars spent per student, along with states like Oklahoma, West Virginia, Idaho, Utah, and Mississippi. In 2015, the state spent $7,590 per student compared to the national average of $11,454. The median salary for a teacher in the US was $57,160 for elementary school teachers and $59,170 for high school, compared with Arizona’s median of $43,280 for elementary school teachers and $46,470 for high school, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. A 2017 study by ASU’s Morrison Institute for Public Policy found that when cost of living was taken into account, Arizona elementary school teachers were the lowest paid in the nation. High school teachers ranked 49th.

Meanwhile, Ducey has styled himself “the education governor.” Last month, his office touted as historic his signing of legislation that extended an existing voter-approved sales tax to fund education. In January, he outlined a five-year plan to put an additional $371 million into education, pitched as a restoration of cuts that came during the Great Recession. The Arizona Daily Star noted that Ducey has himself authorized $348 million of roughly $1 billion in recent cuts to school funding.

In 2017, Ducey announced a 1% pay raise for teachers. It meant an extra $4.13 on Heath’s paycheck. As she sat down to answer, “Who am I?” her anger found a focus.

“My fifth year [of teaching] has made me loathe you as you pat yourself on the back for the pennies a day you've tossed to teachers, feeling certain you've done something more than insult us and our work,” she wrote to Ducey.

“Do you understand that your ‘efforts’ sound much more like a fuck you than a thank you?”

“I love teaching. I love my students,” she continued. “But the actions of this state are slowly squeezing the breath out of all of us. I am suffocating — choking on the apathy of people who don’t care about education, who don’t care about educators. This indifference harms us all — not just teachers — and most importantly, it is a disservice to our youth who are being pushed through this shattered education system; the broken shards snagging them as they move along … Do you understand that your ‘efforts’ sound much more like a fuck you than a thank you?”

The letter to Ducey was long — over 2,100 words — and Heath posted it on LinkedIn, then onto her Facebook page, thinking maybe a handful of friends would read it. As it spread, the response overwhelmed her. Parents of former students thanked her. Teachers from Arizona and beyond shared their own frustrations. She got a couple offers of new tires, one of the expenses she wrote she’d been dreading. When she was accepted into a teacher training program that offered skills to share with her colleagues, she raised $1,400 on GoFundMe to cover tuition and travel expenses.

But by that fall, she knew her career wasn’t sustainable. She entered the 2017–18 school year working through the grief that it would be her last.

Then came the West Virginia teacher strikes. Under grassroots organization, thousands of teachers took to the picket line for a 5% raise and affordable health care coverage. After nine days of canceled classes statewide, they won.

Teachers in other states had been watching closely. In Kentucky, teachers in 25 districts forced closures when they called out sick or absent last month after an overhaul of the pension system. Thousands went on to march at the state capitol.

In Oklahoma, teachers too went on strike, earning a $6,000 pay raise signed by the state’s governor. They continue to rally for more classroom funding, with photos of broken-down facilities and tattered textbooks going viral. A group of about 100 people is marching 110 miles from Tulsa to the state capitol to draw attention to their message.

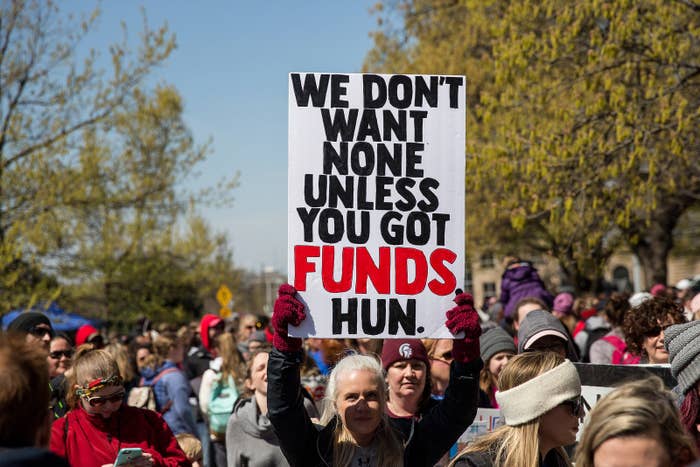

In Arizona, teachers have come together under the hashtag #RedForEd, inspired by the red attire of West Virginia teachers, who were themselves paying tribute to the striking coal miners of the last century. Elementary school music teacher Noah Karvelis started the movement by urging his campus to wear red one day. His efforts over a matter of weeks prompted more than 30,000 people to organize via a Facebook group, a new energy infusing education advocacy in the state.

“We can’t afford to teach and live in this state, and that’s the bottom line,” Karvelis said. “So if [the legislature] won’t bring change, we will by any means necessary.”

So far, Arizona teachers have protested outside the state capitol. They’ve organized “walk-ins” at schools around the state, inviting the local community to come to campus and show their support. And they could still strike. Karvelis’s grassroots Arizona Educators United is demanding a 20% pay increase for teachers, competitive wages for other staff, a return to 2008 school funding levels, yearly raises to bring teachers in line with the national average, and a promise that no taxes will be cut until the state’s education spending reaches the national average.

It’s a list that sounds audacious, said Joe Thomas, president of the Arizona Education Association, the union that represents 20,000 teachers and other staff.

“Who gets a 20% raise? We could get a 20% raise and we would still be beneath the national average,” he said. “These increases we’re asking for look monumental. And they are. They’re almost revolutionary. But even what we’re asking for keeps us in the bottom half of states. And that’s why [teachers] are leaving.”

A day after the protest at the capitol, Ducey told reporters that he continued to support the current budget proposal of a 1% raise this year, and a 1% raise next year.

“I want you to know I’m on the teachers’ side,” Ducey said. “I want to see our teachers get raises.”

His budget proposal puts a new $400 million toward education, Ducey said, adding that dollars available for teacher pay had increased 9% since he took office in 2015. He also disputed the Arizona State University study that ranked Arizona teachers as last in pay nationally, citing the National Education Association statistic that put them at 43rd.

“I’m not bragging on 43rd,” he said. “I’m just saying we’re not last.”

In a statement to BuzzFeed News, the governor’s spokesperson Patrick Ptak said Ducey remains committed to passing that budget within the next few weeks.

“We will not stop here,” Ptak said. “We will continue each year to put more resources into K-12 education to better serve our teachers and students.”

“Really what it comes down to is I want a job where I’m not scared all the time because of my financial situation.”

Teacher advocates have sent a letter to Ducey and legislature leaders, requesting to negotiate on their demands and the governor’s budget proposal. If a deal can’t be reached, teachers are ready to walk out, Thomas said.

“The worst thing that can happen is already happening. We have 5,000 classrooms we can’t find a teacher for. They’ve left permanently. That’s the crisis,” he said. “That’s about 150,000 kids that don’t have the teacher they need to get them to the next grade level.”

And like Heath, some of those who would walk out won’t come back. Seeing her colleagues find their voice has made her feel heartened. But hearing Ducey’s response has brought back the same feelings she vented last year. She doesn’t think things will get much better, and in any case, she has bills to pay.

“Really what it comes down to is I want a job where I’m not scared all the time because of my financial situation,” she said.

The last day of school is May 30, and she said she hasn’t let herself consider the emotions it will bring. She is deciding what her next job will be: commercial real estate maybe, or a position at an education technology company.

Next year, there will be no lessons to plan, no papers to grade, no teenagers depending on her for guidance and support. How will she answer her old assignment, Who Am I?

“I hope I’ll have answers to that question by then.” ●