CENTENNIAL, Colorado — The shooting massacre at an Aurora, Colorado, movie theater has been called unspeakable, horrific, heinous — a crime of the “worst of the worst” that American courts and legislators have determined may be punished with death.

On Friday, jurors in the trial of James Holmes reviewed crime scene video showing the theater hours after the shooting. Bodies of the victims remained where they had fallen, and blood smeared the aisles where those able to flee had spilled their popcorn and dropped their belongings.

The emotion and desire for retribution stirred by such violent loss is understandable, said Denise Maes, public policy director with the American Civil Liberties Union of Colorado.

“If there’s a case for the death penalty, this is it,” she said.

But a lone woman on the jury could not make the moral judgment that death was appropriate for Holmes. Without the jury's unanimous decision for death, Holmes was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

"If you can't get juries to find the death penalty in a case like this, what kind of case in Colorado are you ever going to get the death penalty anymore?" asked Karen Steinhauser, an attorney and adjunct law professor at the University of Denver.

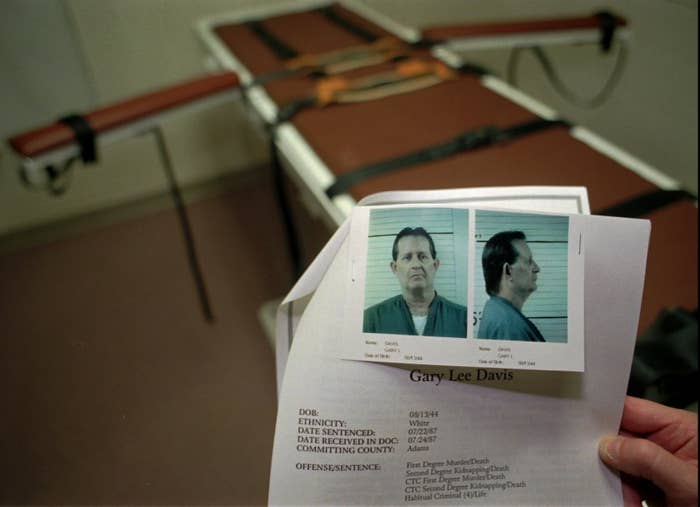

Experts have for years described the death penalty in Colorado as virtually nonexistent. Three men — all of them black and from Aurora — are currently awaiting their death sentence in Colorado. The numbers are so few that the state’s prison system has no official death row. In the entirety of the state’s history, 102 people have been executed, and only one has been put to death since the 1960s.

“We’ve had almost that same number commuted by courts and governors,” said Michael Radelet, a professor of sociology at the University of Colorado.

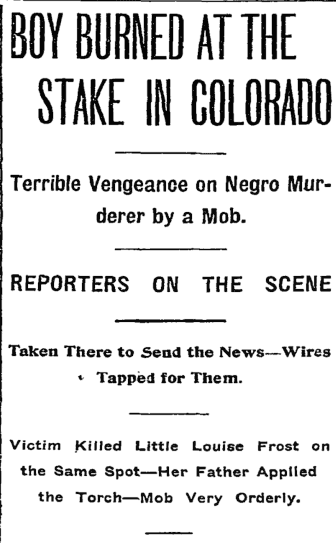

Lawmakers in the past have similarly disputed the appropriateness of state executions. The state first abolished its death penalty in 1897. But Coloradans turned to lynching and mob justice. In 1900, a 16-year-old black boy was burned alive at the stake after being accused of the rape and murder of a 12-year-old white girl. The girl’s father lit the match before a crowd of 300, some of whom had asked the boy for souvenirs.

The New York Times published a detailed front-page story, transmitted by reporters at the scene by a specially installed telegraph. The article noted the crowd as “orderly”; when the boy begged to be shot as his legs caught fire, they added more fuel to the flames.

His brutal death — and the national attention — led to an outcry among Colorado politicians and newspapers for a return to the death penalty.

“Colorado wanted to look sophisticated, and that was bad publicity,” Radelet said.

The death penalty was reinstated in 1901. Since then, various attempts have been made within the state legislature to repeal it, though none have made it to law.

After a repeal bill failed in 2013, District Attorney George Brauchler, who prosecuted Holmes, wrote an opinion piece in the Denver Post. Though he did not name Holmes, he pointed to other mass killers.

“Repealing the death penalty would result in acts similar to those in Newtown, Conn., or the acts of Tim McVeigh being punished no differently than a single murder of one gang member by another,” Brauchler wrote. “Each murder after the first would be a freebie. This is not justice.”

Brauchler repeated those sentiments Friday outside the courthouse after Holmes' sentence was read. He said he respected the jury's decision, though he disagreed with it. He also disagreed that the death penalty in Colorado was effectively finished.

"I don't think this case is a litmus test on that," the prosecutor said.

For now, it's been suspended. In 2013, Gov. John Hickenlooper ordered a reprieve of the death sentence for Nathan Dunlap, the only prisoner facing death who had exhausted his appeals. Hickenlooper said he did not have sympathy for Dunlap, so he was not granting clemency. Rather, the governor cited the divided opinions among residents of the state on the death penalty, as well as the growing difficulty in obtaining execution drugs.

“If the State of Colorado is going to undertake the responsibility of executing a human being, the system must operate flawlessly,” he wrote. “Colorado’s system for capital punishment is not flawless.”

The governor added that the state’s justice system applied death sentences to some murders while choosing life in prison for others of similar magnitude. A question of life or death could be decided by arbitrary factors, he wrote, such as a district attorney’s choice, the defendant’s race or economic circumstance, or the jurisdiction the case was filed in.

“It is a legitimate question whether we as a state should be taking lives,” Hickenlooper wrote.

Research over the years has found that minorities in a single area of the state are more likely to face a death penalty trial than others who might qualify for the punishment.

In a paper published last week, researchers looked at the 546 cases between 1999 and 2010 where the death penalty could legally be applied. Within that pool, prosecutors sought the death penalty 22 times, a use of discretion that the researchers wanted to check for implicit bias.

“The prosecutors have a lot of power,” said Scott Phillips, associated professor of sociology at the University of Denver.

In the 18th Judicial District, home to Aurora, prosecutors were 14 times more likely to seek death against a minority defendant than what white defendants faced statewide — even when controlling for the heinousness of the murders.

“A lot of times, it just comes down to the quirk of who’s elected to be district attorney in a potential jurisdiction,” Phillips said. “That doesn’t have anything to do with the culpability of the defendant or the heinousness of the crime.”

Though a particular case may influence public opinion on the death penalty, Phillips said the problems with the system as a whole shouldn’t be ignored.

“Societies have to have a criminal justice system. We have to have prisons,” he said. “We absolutely don’t have to have a death penalty system. We have to really ask if that’s worth it for a public policy that many states and countries have proven they can live without just fine.”

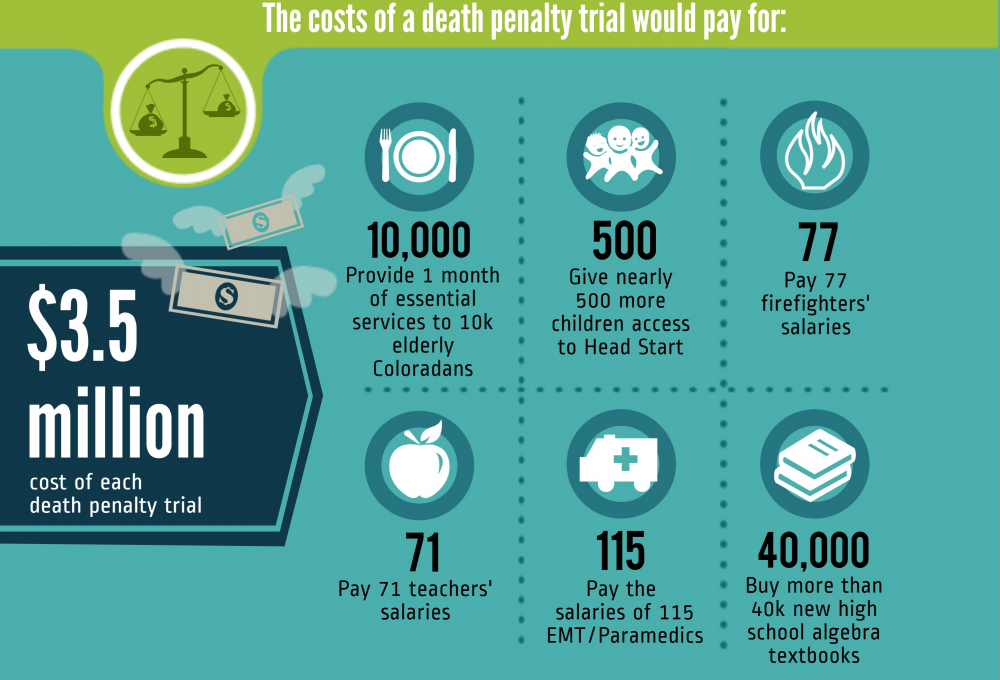

Education on the system’s fairness as well as its costs have been the focus of repeal efforts, Maes said. Under the umbrella of the Better Priorities Initiative, the ACLU has joined families of murder victims, policymakers, and faith leaders to provide information on the problems with the death penalty.

“In a lot of ways, Colorado is a purple state,” she said.

A successful repeal will be the result of bipartisan efforts, Maes said. And the issues with the death penalty — such as whether the $3.5 million cost to taxpayers for each trial is a responsible use of resources — resonate across the political spectrum.

“We are getting the word out that it’s not as easy or simple or a clear-cut case as people think,” she said.