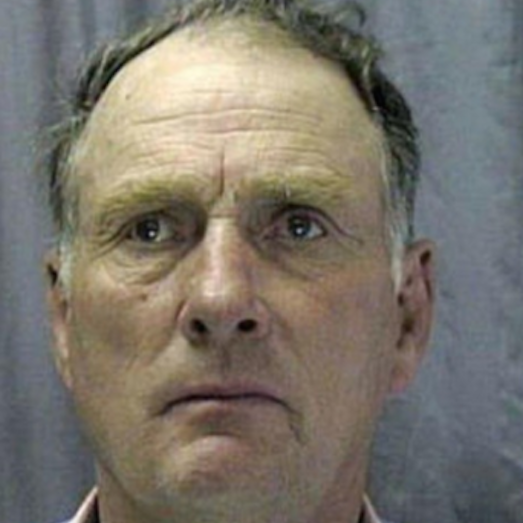

In 1994, Dwight Hammond said he was willing to die to save his ranch.

He also threatened to kill the U.S. Fish and Wildlife officials who got in his way, the manager of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon said at the time.

Hammond — who, with his son, Steven, surrendered at a federal prison on Monday — has for decades clashed with the federal land authorities who own most of the land surrounding his ranch. The disputes have long been a rallying cry for those who see the federal government as overreaching its authority over local residents and their daily lives.

This week, the family’s situation drew supporters to the remote town of Burns, Oregon. It wasn't the first time, but on Saturday, 20 armed men broke off from the group and have since been occupying the headquarters of the wildlife refuge — where they say they’ll stay until the federal government returns the land it has preserved for more than 100 years to local residents.

On Monday, Susan Hammond told BuzzFeed News she didn’t know what to think of the armed occupation at the wildlife refuge. Her husband and son had already arrived at federal prison on Terminal Island in California, where a judge ruled they will serve about four years for arson on federal land.

For the Hammond family, the situation has always been personal.

“It's our livelihood,” Dwight Hammond told CNN in 1995. “It's our — it's everything. It's life itself.”

The Hammonds, already a prominent family in Harney County, would come to be the face of long-simmering grievances between ranchers and the federal government, one that would see occupiers dig in against brutally cold temperatures and an increasingly frustrated local sheriff on Wednesday.

Though government agencies have said they're simply following the law to preserve the public lands of the West, a number of ranchers and land use advocates instead see the regulation as an attack.

Dwight Hammond first made national headlines after he was arrested on suspicion of forcibly impeding, intimidating, and interfering with federal officers engaged in official duties. The case was later dropped.

The incident stemmed from a dispute over a fence. In 1994, U.S. Fish and Wildlife began to build a fence blocking Hammond’s cattle from foraging for food and water. Authorities said a grazing permit had been revoked, but Hammond said he maintained water rights.

A piece of Dwight Hammond’s farm equipment blocked the fence building, and the verbal dispute began.

Forrest Cameron, who was then the manager of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, told the Chicago Tribune that the rancher threatened to kill him as he tried to do his job. Dwight Hammond told CNN the alleged threat may have been a misperception.

“I've said that I was willing to die,” he said. “Maybe they're willing to die. I don't know.”

Dwight Hammond was released from custody after pleading not guilty, and three years later, court records show the case was dismissed.

In 2011, the disputes between the family and federal authorities again reached the level of criminal charges. Dwight Hammond and his son were accused of setting wildfires over the course of years that reached into federal lands — costing the government thousands of dollars to put out the fires, as well as putting federal employees at risk, prosecutors said.

Prosecutors said the family intentionally set the fires to destroy juniper and sagebrush to make way for grass and grazing. Though the Hammonds held grazing rights, burning the public land required approval from the government. But prosecutors alleged the family was fed up with the lengthy process of environmental study required by the Bureau of Land Management before controlled burns.

Joe Glascock, a Bureau of Land Management conservation manager, confronted the men with a sheriff official about the fires in 2006. At trial, prosecutors said Steve Hammond told Glascock the situation could get “sticky” if the fire investigation wasn’t dropped.

“If you want to stay here, you'll make this go away,” the rancher said, per the prosecutor. “If I go down, I'm taking you with me. You lighted those fires, not me.”

The Hammonds had been ranchers for generations, defense lawyers said, working on a patchwork of private and federal land to which they held grazing rights. In the rugged, remote terrain, establishing exactly who was where at the time of a fire — as well as whether it was arson — wouldn’t be easy, defense lawyers said.

A number of the charges, including witness tampering, were dismissed. Ultimately, Dwight and Steven Hammond were convicted of using fire to damage and destroy the property of the United States.

Despite of a statutory requirement for a minimum five-year prison sentence, a district judge ruled that length would be cruel and unusual punishment — Congress likely didn’t intend for the statute to cover fires in the “wilderness,” the judge said. Instead, Dwight Hammond was sentenced to three months in prison, Steven Hammond to 12 months and one day.

But a federal appeals court later ruled the reduced sentences were illegal and called the Hammonds back to prison to serve the rest of their five years.

Steve & Dwight Hammond surrender

“A minimum sentence mandated by statute is not a suggestion that courts have discretion to disregard,” the appellate court ruled.

Arson is a serious crime, and it is constitutional to punish it with five years in prison, the court added.

“Even a fire in a remote area has the potential to spread to more populated areas, threaten local property and residents, or endanger the firefighters called to battle the blaze," the court said. "The September 2001 fire here, which nearly burned a teenager and damaged grazing land, illustrates this very point.”

Before starting the journey to prison on Saturday, Dwight Hammond spoke to the more than 100 protesters who had gathered in support of him and his son, telling them that what may have started decades ago as one man trying to protect his livelihood was now much bigger, The Guardian reported.

“Remember, this is not about me," he said. "This is about our country.”