CHARLESTON, South Carolina — As Joseph McGill waited for visitors to assemble at the train depot for his From Slavery to Freedom tour on a Monday afternoon, an older white couple approached. They wanted to know if the waiting tram ahead, packed with people, was for the nature tour.

It was, McGill said, and pointed the couple on their way. His tram, on the other hand, sat nearly empty — seven people and a toddler. This isn’t unusual.

McGill has worked as a guide at Magnolia Plantation and Gardens, a 30-minute drive from downtown Charleston, South Carolina, since 2011. Established in 1676 by the Drayton family, black slaves were forced to till the land for rice production. Today, Magnolia is mostly known for its sprawling gardens, which the family opened to the public in the 1870s after the Civil War. It has a petting zoo, a seasonal Chinese Lantern Festival display, and five tours, and it is a popular wedding venue.

Though thousands of people visit Magnolia every year — it bills itself as “Charleston’s Most Visited Plantation,” though administrators declined to say how many visitors it receives — McGill’s slavery tour is the one attraction that, according to him, “is chosen the least.”

There’s no guarantee that you’ll learn much about Magnolia’s enslaved people unless you go on the 45-minute tour. Guides on other tours may mention slavery in passing, but because Magnolia, like many plantations, provides guides with interpretive notes rather than a uniform script to follow, what tourists hear varies widely.

Visitors often try to “avoid that subject matter as much as possible,” McGill said. “It puts them in an uncomfortable place. We are folks who want to be comfortable, that’s a natural instinct. Dealing with the atrocities of the past takes us away from that, and slavery is one of those atrocities.”

Plantations are massively popular attractions in the South, where tourists flock for their beauty and to learn about the families who enslaved people, many of whom were important historical figures. Most tourists don’t go to plantations to learn about the enslaved people who made the white planters wealthy, whose subjugation in the ships that brought them to the States continued on these very grounds, whose culture was stamped out and descendants exploited.

The way these sites operate, from their admission structure to the presentations from the tour guides, often enables visitors to easily avoid any real encounters with their history of slavery. It underscores a fundamental dilemma for these sites: The business of attracting tourists and making money often clashes with efforts to present a more comprehensive history of its participation and perpetuation of the horrors of slavery in America.

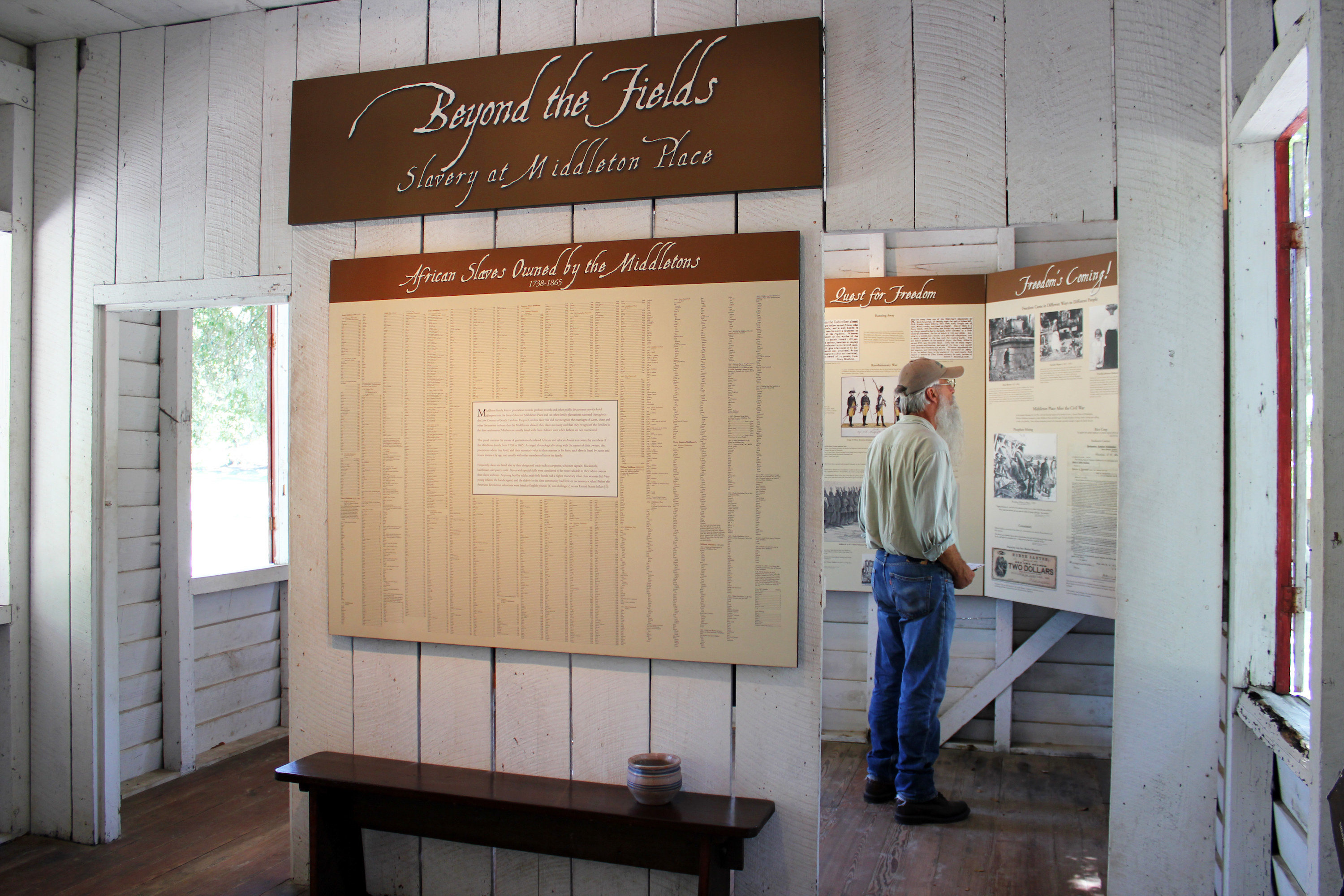

In February, BuzzFeed News visited three plantations around Charleston, South Carolina, that differed in their approach to addressing this history. At Magnolia, McGill’s honest and affecting From Slavery to Freedom tour emphasized the glaring absence of that history in the rest of the site’s attractions. At Middleton Place, where employees told BuzzFeed News about its mission to honor the stories of enslaved people and enslavers, a guide for its slavery-focused Beyond the Fields tour did not live up to it. At McLeod Plantation, the focus is explicitly on the enslaved people; the white enslavers are secondary.

For Magnolia’s From Slavery to Freedom tour, visitors board a tram that jangles down a dirt road to get to the restored cabins where enslaved people lived. It’s a short ride, but the isolation of the cabins from the rest of the site’s attractions is noticeable.

It costs $20 for general admission to Magnolia, and each of its five tours is an additional $8. It adds up — especially for families — and many have expressed their unhappiness with Magnolia’s steep prices in Tripadvisor reviews.

Visitors can book a Magnolia tour package through one of Charleston’s many tour companies at a slightly lower cost. Tour companies that top Google’s search results offer packages for Magnolia that include the admission fee, transportation to and from downtown Charleston, and a number of guided tours — but not the slavery tour. A representative for Gray Line, which only offers Magnolia’s house and nature tours in its package, told BuzzFeed News the company includes only the site’s most popular tours.

McGill, who worked as a part-time guide at Magnolia until he was hired full time this January as a history and culture coordinator, is currently incorporating a more thorough history of slavery into the plantation’s other tours so that visitors don’t leave without learning about it. “We just want to ensure that whatever tour they choose,” he said, “they’re going to hear the stories of enslaved people.”

At Middleton Place, nearly four miles north of Magnolia, the first sign past the entry portal acknowledges the enslaved people who worked and lived there.

The former rice plantation was one of the Middleton family’s 20 in South Carolina. From 1738 to 1865, the Middletons enslaved at least 2,800 people whose names and monetary worth are listed on a plaque at Eliza’s House, the starting point of the Beyond the Fields guided tour about slavery.

Unlike Magnolia, Middleton Place’s tour is included in the $29 admission. The House Museum tour, where visitors get to see a collection of artifacts and learn about the Middleton family’s historic importance, costs an extra $15, and the horse-drawn carriage another $18.

Today it’s run by the nonprofit Middleton Place Foundation and bears the National Historic Landmark designation. It has panoramic gardens and fields where sheep roam, a row of stable yards, and an interpretive area that houses shops selling the work of costumed employees who knit, make pottery, and forge iron and steel products as they educate visitors about enslaved artisans at Middleton. There is a renowned restaurant and a three-star hotel, and it hosts crafting classes, wine tastings, and, once a year, a naturalization ceremony for new citizens.

Don Bussey, Middleton Place’s director of marketing and public relations, is careful to note that the foundation sets out to tell the history of its enslaved people and the Middletons in equal measure.

Guides and historical interpreters, a majority of whom are volunteers, do not follow a script for their presentations, Bussey told BuzzFeed News, but Middleton Place provides them with training materials that tell the story about the place “the way we believe it should be told.”

“This is not a story that we should paper over. This is not ever going to be — to use the cliché term — ‘moonlight magnolias’ kind of tour for people,” he said. “We want them to know about what happened here.”

“Moonlight and magnolias” is a reference to the antebellum South, a romanticized idea of Southern life perpetuated in films like Gone With the Wind, ignoring and obscuring the realities of slavery.

The subtext on any plantation is that for a long time, enslaved people were the majority there, and they lived under the prospect of terror and brutality, Bernard Powers, the founding director of the College of Charleston’s Center for the Study of Slavery in Charleston, told BuzzFeed News.

“Sometimes people, when they think of a historic site, they think of only what they see in front of them, which is beauty: the moonlight and magnolias kind of image,” he said.

Still, Middleton Place’s mission to honor the lives and contributions of enslaved people doesn’t always translate on a guided tour.

On a weekday afternoon in February, an older white guide opened his Beyond the Fields tour by saying that slavery was not exclusively an American institution, but acknowledged that the American system was, as he described, “quite strict.” (In fact, the system of chattel slavery in America enslaved black people and their descendants, who were considered legal property, from birth until death with no real recourse to freedom.)

He spoke about the institution of slavery in passive terms — “they were brought here” and “they came here” — and from the perspective of slave traders and enslavers. At one point, he asked that the group try to understand the background and culture in which white Americans were taught that slavery was acceptable. He also noted that not every white South Carolinian at the time enslaved people, unlike what “Hollywood” might want people to think.

Jill Paperno, a woman from Rochester, New York, who visited Middleton Place on a different day in February, told BuzzFeed News she read some reviews online and chose Middleton because she was interested in seeing the gardens and wanted to learn about the day-to-day lives of the enslaved people.

But it was a letdown.

While she felt a presentation put on for Black History Month, “Mama Hattie Remembers,” was powerful and moving, the two guided tours she took there, one of them being the Beyond the Fields tour, left her deeply unhappy.

“I was very angry when I left there,” Paperno said.

In a Tripadvisor review, she wrote that the guide for Beyond the Fields, also an older white man — it’s unclear if he was the same guide BuzzFeed News toured with — talked broadly about the institution of slavery and the Middletons’ Rhode Island summer home, but not about the realities of slavery, until she asked pointed questions.

When the group came across the plaque with the names of people the Middletons enslaved, Paperno told BuzzFeed News it was a “really powerful and upsetting” moment for her.

But the guide, she said, only “kind of acknowledged it.”

“I stood in front of that and I was kind of blown away,” she recalled. “And that was just an aside to him in a way.”

Paperno wrote in her review that she felt the guide “whitewashed the reality of slavery” on the tour.

“I was thinking about how he made it seem almost idyllic, you know — they could go fishing and hunting and play with their children if they just got their work done. So there was a sense that slave owners weren’t cruel and inhumane,” she told BuzzFeed News. “You just didn’t get the sense through the tour that there was this brutality unless there were pointed questions about it, which there weren’t many of.”

If Paperno felt like this as an older white woman, she said, “I can’t even imagine what the experience would have been like had I been African American.”

Most of Middleton’s guides are volunteers, Bussey said. Some of them, he acknowledged, may make questionable statements on their tours.

“It happens, and it’s difficult to correct when you’re talking about volunteers,” he said.

Middleton keeps a close eye on Tripadvisor reviews, often responding to criticism from visitors that leadership believes is “factually incorrect,” Bussey said. The reviews also help them identify guides whom visitors criticize so that leadership can “encourage them to rethink the way they may present a particular point.”

Tourism is crucial for plantations in Charleston. Though many sites don’t document or publicize the racial demographics of their visitors, employees at several plantations told BuzzFeed News that the people they see visiting these sites are overwhelmingly white.

“There are not a lot of us — people who look like me — who come on plantations,” McGill said. “This is not on our shortlist of places to visit.”

A lot of that, McGill said, is because many plantations have been slow to incorporate the stories of enslaved people in their narrative about the site’s history.

Ten, twenty years ago, “we would get a failing grade in the aspects of us telling the stories of the enslaved,” he said, noting that overall, these sites are “doing an adequate job” now.

“With that you will see an increased number of people of African descent coming to these places [and] people of color in general coming to places like that,” McGill added.

The increase in black visitors is evident at McLeod Plantation, according to its employees. Located on James Island, McLeod, which is run by the Charleston County Parks and Recreation Commission, focuses on the lives of enslaved people and subsequent occupants of the site after the Civil War, rather than the McLeod family.

At McLeod, the main house, often the centerpiece of many plantations where guides talk about the white family of enslavers, is unfurnished and has no guided tours. Instead, there are exhibits focusing on enslaved people, as well as the soldiers and freedmen who later occupied the property. McLeod has a more somber atmosphere than other plantations around Charleston, and with only one guided tour about the enslaved people, admission is notably more affordable at $15.

Olivia Williams, a historical interpreter at McLeod, told BuzzFeed News the number of black visitors has “skyrocketed” in the past year or two.

Charleston County Parks has been making a concerted effort to advertise to black travelers, marketing director Renee Dickinson said. But McLeod has also received some media attention in recent years due to its approach to interpreting the history of enslaved people, which has stoked backlash, as well as overwhelming praise.

Williams said she’s seen more black families visiting McLeod over the summer, from both the US and Africa.

“And they’ll be very candid and be like, ‘Prior to this the thought of going on a plantation made us really uncomfortable, but this showed us they’re not all the same,’” Williams said.

Many plantations function as more than a historical site and tourist attraction. In Charleston, they are highly coveted wedding venues that book out years in advance, boosting the city’s reputation as a wedding hot spot.

In December, the news that wedding planning websites would stop promoting vendors that romanticize former slave plantations led to some backlash, which alarmed many in Charleston, where tourism and weddings go hand in hand.

Plantation weddings can be expensive. A ceremony at Magnolia Plantation can set you back $7,500. At Middleton Place, couples are expected to hire the on-site restaurant to caterer the wedding reception on top of shelling out for rental space, which alone can cost $9,500. At Boone Hall Plantation and Gardens, which famously hosted Ryan Reynolds and Blake Lively’s wedding, rates range from $800 to $7,500 for the venue.

The money made from weddings can go a long way in keeping the plantation running, Powers, the College of Charleston’s Center for the Study of Slavery director, said.

“That kind of activity could be an important source of revenue for them, which then can allow them to do the other work that they do: the research, and hiring staff, and so on and so forth,” he said.

That is true for Middleton Place, according to blacksmith and historical interpreter Jamal Hall.

“On one hand I feel as though, like, yes, these are plantations, they should be held as places like memorials, places of respect, places of reverence for the people that worked by force and died here. But at the same time what I think a lot of people don’t really understand is that these weddings are what keeps everything running here,” he said. “The weddings pay for the sheep, for the grass to get cut, for the coal in my shop, for the metal that I use, for the clothing that I wear right now. For the programs that we do out here.”

Hall said there are no easy answers to plantation weddings.

“Until we find an alternative source of funding, if there is such a thing out there, weddings are what we have to go off,” he said. “It’s ideally not the best way of getting that money, it’s what we have.”

Bussey, Middleton’s marketing manager, told BuzzFeed News that there are efforts to get more funding, but “not necessarily in the context of replacing weddings.”

“I’m not trying to suggest that we don’t want weddings here by any stretch of the imagination,” he said. “And we certainly aren’t going to be in the business of discouraging people from coming here.”

The “moonlight and magnolia” ideal is key to plantations marketing themselves as wedding venues, even if they are trying to be more up front about their history of slavery. Several people BuzzFeed News spoke to previously said they wanted to get married at Boone Hall Plantation because of its beauty and history — a version of history, Powers said, in which slavery is often ignored.

Couples who marry on plantations see these sites as “beautiful and historical,” Powers said, but their idea of the place’s history lacks context. “It’s the matter of being old — that’s what history means to people sometimes, not really the crimes that we know actually happened at these places,” he said.

This tension is even sharper in a place like McLeod, which held weddings since it opened to the public in 2015 for years — even as it offered a clear acknowledgment of slavery. Photos posted online show ceremonies taking place outdoors, with the McLeod house serving as a backdrop.

After years of internal deliberation, McLeod decided to stop offering weddings in fall 2019, Dickinson, the Charleston County Parks marketing director, told BuzzFeed News. (It is honoring reservations made prior to that change.)

“I think it was something we just felt we weren’t sure if it was the right fit, and then it really started to become clear to us that it wasn’t. And we decided to stop them,” she said.

According to an archived version of its event rental webpage, a “plantation ceremony” cost $2,000, and for another $1,000 the couple could use the outdoor pavilion area as well, which lies across the main road from the entrance along the river.

Today the event rental page only has one option: $2,000 for the pavilion.

According to Dickinson, the events McLeod wants to host are ones where there can be an “educational component.”

“A wedding is not necessarily an event that has that kind of opportunity is it?” she said. “[Weddings] just didn’t offer that opportunity and we just didn’t see the likelihood of that happening.”

Christine Mitchell, an educator and historical interpreter at the Old Slave Mart Museum in downtown Charleston, worked at McLeod as an interpreter for about a year when it opened. For her, the dissonance between being an educational site about slavery and a wedding venue was immediately clear.

But Mitchell said she only learned that the plantation was going to be a wedding venue after she was hired.

“I would have turned down employment or probably wouldn’t have applied in the first place if I had known that up front,” she told BuzzFeed News. “My ancestors have already paid the price through their blood, sweat, and tears working on these plantations. To now be making money off of them — yeah, I was upset about that at McLeod.”

She stopped working at McLeod shortly after.