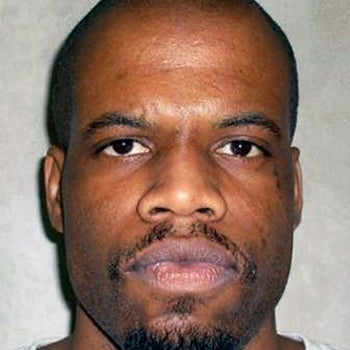

Last year, an Oklahoma inmate sat on a gurney for 43 minutes while the drugs that were supposed to course swiftly through his body and kill him failed to do so.

Any day now, the Supreme Court is expected to issue a decision in a case on whether Oklahoma's death penalty protocol is constitutional, a case filed in the aftermath of that botched execution, many of the details of which still remain shrouded in secrecy. How the Supreme Court will decide — how narrowly or broadly or whether they will issue an opinion at all — is unknown.

One thing is clear, however, in Oklahoma and elsewhere: The way people are executed in America is increasingly done in secret.

The identities of the actual executioners have been secret for a long time. But in recent years, states have extended that same secrecy to the very drugs used to kill people — where they're purchased, how they're purchased, and how they're prepared and administered.

Death penalty lawyers argue the secrecy means they don't find out about many of the problems until something goes wrong. But even in those cases, investigations are done by the state itself, shielding an unknown amount of that information — beyond what the state releases — from public disclosure.

Lockett's execution took place more than a year ago, yet reporters in Oklahoma are still waiting for Gov. Mary Fallin's office to turn over emails and records from that night. Eventually Ziva Branstetter, a journalist now with the Tulsa Frontier, had little choice but to sue for the documents in December of last year.

Fallin has attempted to delay the suit — arguing that, although her office hasn't turned over the records, she hasn't formally denied the request either. Fallin's office claimed in court that absent a formal denial, the courts couldn't weigh in.

The response from Fallin isn't an anomaly, either. Her office has stopped responding to emails about a BuzzFeed News open records request from months ago.

In a statement, a Fallin spokesperson said the governor was committed to transparency.

"It is an extremely time-consuming process," Alex Weintz said. "And, since our office gets many Open Records requests, it can take a while to receive documents in response to a request."

The situation in Oklahoma isn't unusual.

"Departments of Corrections have realized that the more information they provide, the more it reveals how little they know," said Deborah Denno, a law professor who has followed the death penalty for decades.

"It's always been there, but now it's becoming more pronounced. The only time we really find out what's going on is when something goes wrong and we have a really badly botched execution."

The secrecy has also provided cover when things go wrong. That's how it has played out in Georgia after state officials had to halt an impending execution after finding particles floating in the syringe.

Georgia officials said the state would put its executions on hold while it investigated what went wrong. Attorney Gerald "Bo" King, who represents the woman on death row, worried that the "self-investigation" would be biased.

"[The state] will not be merely the subject of this investigation; they will also conduct it," King wrote in March. "And they will hide all critical aspects of their self-assessment from Ms. Gissendaner, the public, and this court."

Those concerns have been borne out in the time since. After a short investigation, Georgia told the courts, the press, and the public that the likeliest cause of the drug's issues is that it was stored at too low of a temperature. But state officials did not publicize the fact that the expert consulted by the state also pointed to a second possible cause — problems with how the drug was made. The state then withheld the results of a test that could support or cast doubt on that assessment, refusing to turn those results over to BuzzFeed News in an open records request.

"After reflection," — and a BuzzFeed News report detailing how the state was withholding the results — the state changed its mind and released them. The results cast doubt on their assessment that it was temperature, and not a problem with the secret pharmacist that mixed the drug, that caused the drug to go bad.

The lethal injection problems have not appeared to change the minds of those who have supported the secrecy.

"Georgia did they right thing, they didn't use the drug. It's not a problem," said Kent Scheidegger of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, an organization that works to support the death penalty. "Oklahoma — they did have one case where the insertion wasn't done correctly. But they've taken steps to fix it."

Scheidegger and other supporters argue that the secrecy is vital. Without it, he says, people wouldn't be willing to participate in executions or sell lethal drugs.

"I cannot think of another instance where companies would face the same criticism for participating in a government function," Scheidegger said.

Military companies aren't shielded from public scrutiny, and the amounts the government pays those companies are a matter of public record. When asked why this should be different, Scheidegger said, "I lived through Vietnam era and I don't remember them doing this with military contractors."

"As long as the drug is tested, it shouldn't matter where it comes from," he added.

It's the argument that almost all other states have made when the secrecy has been challenged.

In fact, these days, Nebraska seems to be the only state fine with turning over records that illustrate how its lethal drugs are procured, even if the Food and Drug Administration has said those drugs are illegal and will be seized.

Nebraska's lethal injection drugs are purchased from a supplier in India.