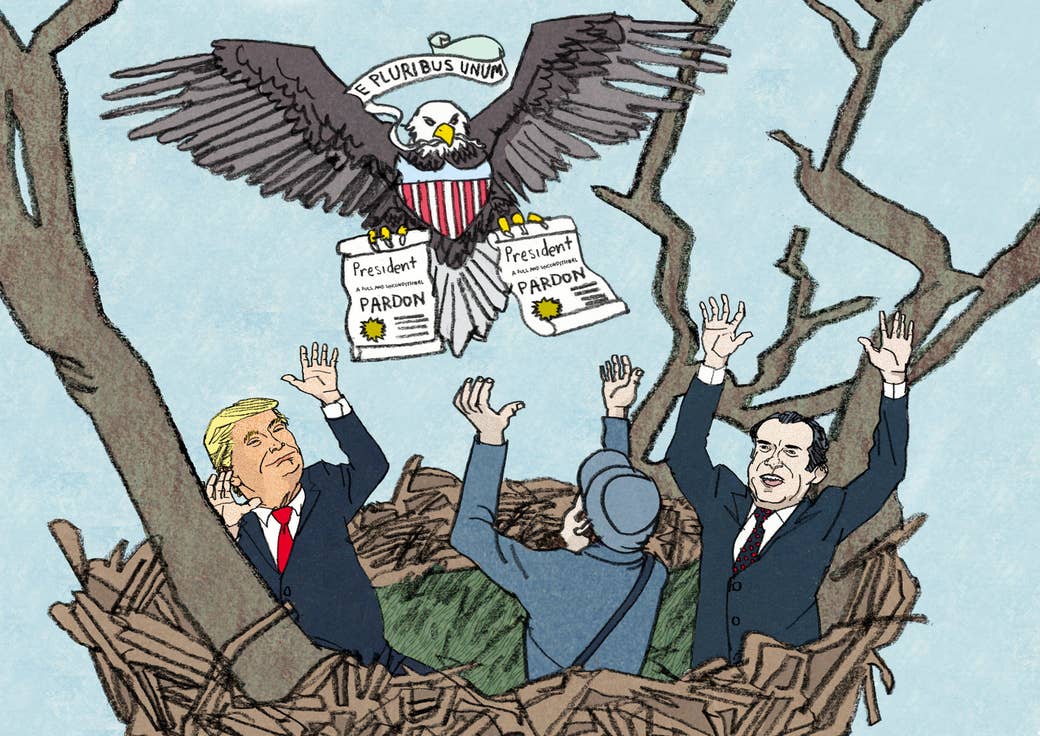

President Trump has yet to announce a grant of a single pardon or commutation.

But he already has signaled — in a Saturday morning tweet, of course — that his use of that power could be expansive. He wrote that everyone agrees he "has the complete power to pardon."

Here’s the thing: By and large, he’s not wrong.

The Constitution is short and to the point on pardon power: “[H]e shall have power to grant reprieves and pardons for offenses against the United States, except in cases of impeachment.”

The contours and confines of that power, however, are limited because only 43 people have ever exercised the federal pardon power. As with many aspects of presidential power, there have been limited challenges in court to the pardon power as a result — and scattered case law interpreting exactly what the American president’s pardon power means (and doesn’t mean).

The Supreme Court has, over time, heard several cases detailing the limits of the power. But not that many cases reach the Supreme Court, and that consideration has been limited to the specific cases that have reached it. The courts have made clear over time that presidents can pardon people before they’ve even been convicted of any crime; that any federal offense can be pardoned; and that presidents are given broad leeway in the type of relief they can grant — from temporary reprieves to full pardons to commutations to broad-based grants of amnesty.

The Supreme Court, however, has never definitively answered some key questions about the extent of the pardon power.

William Howard Taft, the one person in US history who served as both president and chief justice in his life, laid out a succinct description of the only real recourse to deal with a president who abuses the pardon power.

“Our Constitution confers this discretion on the highest officer in the nation in confidence that he will not abuse it,” Taft wrote in a 1925 decision for the Supreme Court. But what if a president did abuse it? Taft outlined a hypothetical scenario in which a president granted successive pardons to prevent a court from enforcing its orders. He was blunt with what the solution would be: “Exceptional cases like this if to be imagined at all would suggest a resort to impeachment rather than to a narrow and strained construction of the general powers of the President.”

To understand the pardon power in American government, how it’s been used, and its limits requires a wild trip through some of the most difficult and weirdest moments in US history.

Throughout it all, with rare exception, the answer to what the president can do when it comes to pardons is remarkably consistent:

Yes, he can do that.

The Convention

At the outset, the founding fathers decided to grant the president extremely broad pardon powers — drawn, in many ways, from British history and the king’s authority to pardon. As Jeffrey Crouch details in his book, The Presidential Pardon Power, the constitutional convention rejected several proposals to limit the pardon power over the course of the drafting.

The states rejected a proposal to require Senate consent for pardons. The convention rejected a requirement that would have limited the president to granting pardons only “after conviction.”

“Some at the 1787 constitutional convention in Philadelphia argued that granting the president the unlimited power to pardon in cases of treason was too dangerous,” Capital University Law School professor Daniel Kobil wrote recently. Many of the delegates saw the dangers possible from such a power — but, Kobil notes, “they could not identify an acceptable compromise and so the federal system vests the power to pardon treason in the president.”

Some of the concerns regarding pardons for treason, as set forth in the records of the convention, included circumstances in which the president himself or his associates could be involved.

“The President may himself be guilty. The Traytors [sic] may be his own instruments,” some argued.

The response to that argument: “If he be himself a party to the guilt he can be impeached and prosecuted.” That became the guiding principle of the pardon power: The constitutional convention’s only real exception to the president’s power to pardon federal offenses is that pardons do not extend to “cases of impeachment.”

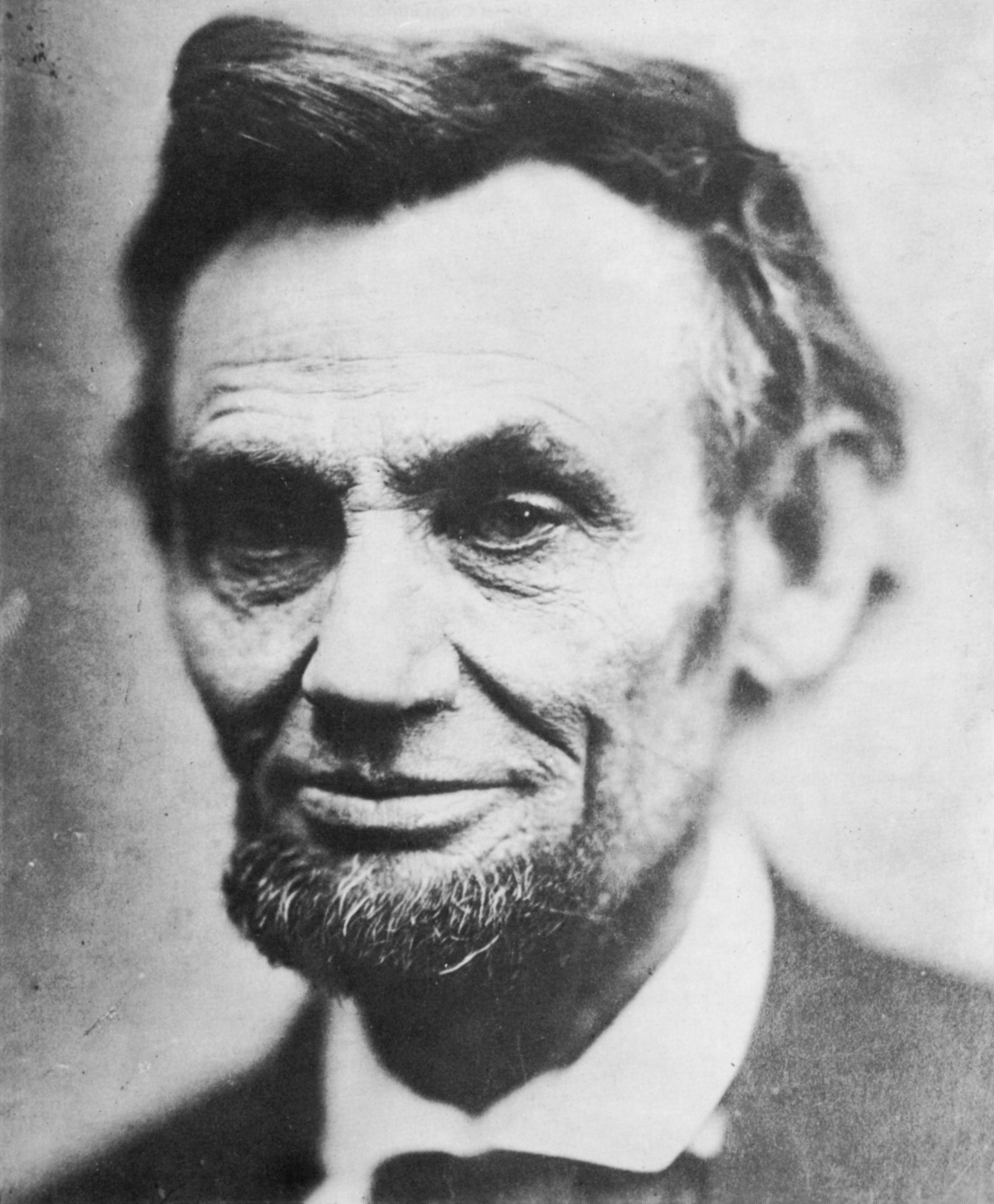

The Civil War

As the Civil War continued into its second year, President Lincoln began issuing grants of amnesty to those people who had supported or in some way aided the secession, a practice Johnson continued after the Civil War. Although some of the initial grants were made with backing from Congress, the lawmakers later pushed back — seeking to limit the effects of the amnesty grants.

But as quickly as Congress could find news ways to limit the amnesty grants, the Supreme Court almost uniformly rejected them.

The Supreme Court announced in April 1870, for example, that a person who had “participated in the rebellion” could have previously confiscated property returned to them under a presidential grant of amnesty — exercised under the pardon power.

By that summer, Congress had passed a provision into law limiting the president’s amnesty power, asserting that “no pardon or amnesty granted by the President … shall be admissible in evidence” in court in an attempt to get back confiscated property.

But a year later, the Supreme Court held that Congress could not curtail either the court or the president’s powers like that.

The courts had previously determined that the amnesty grants could be used as evidence in attempts to get back confiscated property. Congress had, effectively, tried to reverse that by having “forbidden” the courts from using the clemency grant in that way. This went too far, Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase wrote (albeit using very soft language): “We must think that Congress has inadvertently passed the limit which separates the legislative from the judicial power.”

Additionally, Chase wrote that the law violated the pardon power: “To the executive alone is interested the power of the pardon; and it is granted without limit.” He added that “it is clear that the legislature cannot change the the effect of such a pardon any more than the executive can change a law.”

Still, during this period, the court established the first real limit to the pardon power. The Supreme Court held that a pardoned person could not use their pardon or amnesty grant as a way to get back property that had been taken from them if that property already had been transferred to a third party.

In 1877, the Supreme Court held that a pardon does not “affect any rights which have vested in others directly” because of the conviction for which a person has been pardoned. “If, for example, by the judgment a sale of the offender's property has been had, the purchaser will hold the property notwithstanding the subsequent pardon.” While the case did not directly limit the president’s right to grant a pardon, it did establish limits in the court’s understanding of the effects of a pardon.

“However large,” Justice Stephen Johnson Field wrote, “may be the power of pardon possessed by the President, and however extended may be its application, there is this limit to it, as there is to all his powers, it cannot touch moneys in the treasury of the United States, except expressly authorized by act of Congress. The Constitution places this restriction upon the pardoning power.”

In other words, the president can pardon whomever he wants. But in order for a pardoned person to receive compensation or other funds from the US Treasury, Congress would need to approve it.

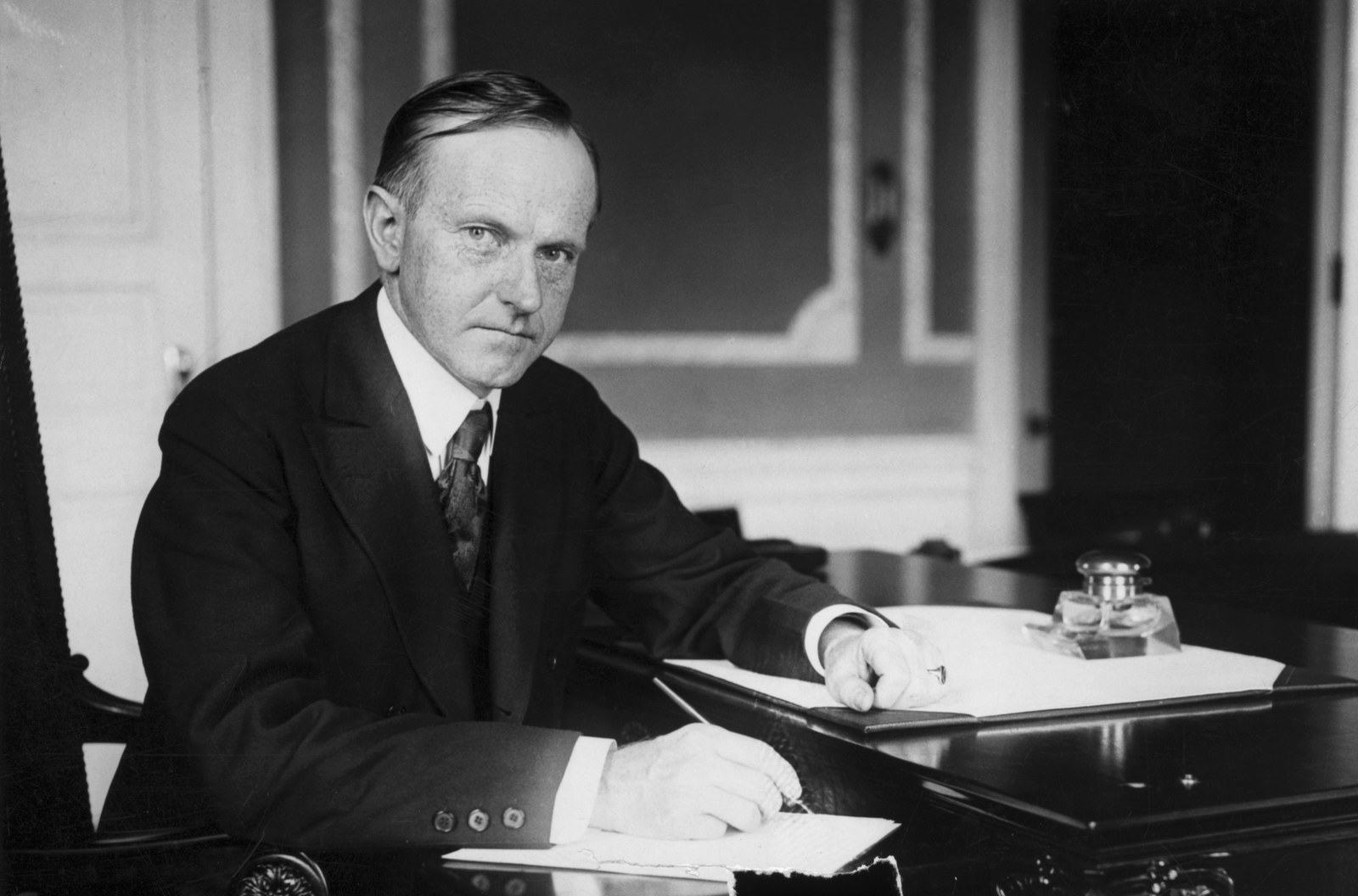

Bootleggers

Courts ruled in favor of the broad expanse of the pardon power yet again in an otherwise minor case of a bootlegger named Philip Grossman.

The president’s power, the court made clear at that time, even reached to extinguishing criminal contempt citations.

In November 1920, federal prosecutors alleged that Grossman “was maintaining a nuisance” at his business because he was selling liquor in violation of the National Prohibition Act. A district court judge granted a restraining order barring him from continuing to do so.

Two days after the order had been entered against him, though, federal officials were back in court, alleging that Grossman continued to sell liquor in violation of the restraining order. “He was arrested, tried, found guilty of contempt,” and sentenced to serve a year in prison and pay a $1,000 fine. Grossman unsuccessfully appealed.

In December 1923, however — before he was done serving his sentence — President Calvin Coolidge commuted Grossman’s sentence on the condition that he pay the fine. Grossman did so and was released.

Nonetheless, the district court brought Grossman back in to serve his sentence — “notwithstanding the pardon.”

This was unacceptable, Chief Justice William Howard Taft wrote for the court.

The opinion is particularly notable because the former president, now chief justice, wrote a decision laying out the confines of judicial and executive powers. “Nothing in the ordinary meaning of the words ‘offenses against the United States’ excludes criminal contempts,” Taft wrote, noting a distinction between civil contempt (which is used to coerce a person to do something) and criminal contempt (which is used to punish a person for past behavior). Taft added that criminal contempts from federal courts had “been pardoned for 85 years” — specifically, 27 times.

Taft also wrote broadly about why, at the end of the day, the president’s pardon power, in effect, overturns a court’s judgment — and how the separation of powers actually functions.

“Complete independence and separation between the three branches, however, are not attained, or intended,” Taft wrote, laying out numerous instances of overlapping powers, from the veto power to impeachment and removal to pardons to holding up appropriations or presidential appointments. “These are some instances of positive and negative restraints possibly available under the Constitution to each branch of the government in defeat of the action of the other.”

Taft acknowledged, moreover that “[t]he administration of justice by the courts is not necessarily always wise” — courts sometimes get it wrong. He wrote that the “remedy” has been “to vest in some other authority than the courts [the] power to ameliorate or avoid particular criminal judgments.” In the US, he wrote, that authority is the president and the power is the pardon.

The Nixon Pardon

On August 5, 1974, Mary C. Lawton, the acting assistant attorney general in the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, hand-delivered a three-page memorandum to the deputy attorney general. Her memo concerned the question of whether President Richard Nixon could pardon himself.

“Under the fundamental rule that no one may be a judge in his own case, it would seem that the question should be answered in the negative,” Lawton wrote.

But Lawton proposed a possible work-around: Nixon, she argued, could step down temporarily under the 25th Amendment, at which point the vice president — as acting president — could pardon Nixon. “Thereafter the President could either resign or resume the duties of his office,” she wrote.

Nixon resigned four days later.

President Gerald Ford nonetheless pardoned Nixon on Sept. 8, 1974, for all crimes that he “committed or may have committed or taken part in” during his presidency.

That proved politically disastrous, a decision that hindered Ford’s presidency — but also reverberated for decades to come and made the use of the pardon both more high profile and less common.

But Ford’s decision illustrated the breadth and expanse of the president’s power — he pardoned Nixon on Sept. 8, 1974, for all crimes that he “committed or may have committed or taken part in” during his presidency.

Jimmy Hoffa

Less than a month before Nixon’s resignation, a federal judge in Washington, DC, issued a ruling in a key case about the extent of the president’s pardon power.

The case raised one of the key unanswered questions about the scope of the pardon power: What conditions can a president attach to a pardon that would make it an unconstitutional abuse of the president’s power?

On Dec. 23, 1971, Nixon pardoned former Teamsters president Jimmy Hoffa, who was then serving a prison sentence that would have kept him behind bars through 1980. In doing so, however, Nixon only commuted Hoffa’s sentence “upon the condition that the said James R. Hoffa not engage in direct or indirect management of any labor organization prior to March sixth, 1980.”

Once out of prison, however, Hoffa challenged the condition on several grounds, arguing that it violated his First Amendment rights to free speech and association, criminal procedure rights under the Fifth Amendment, and due process rights.

US District Judge John Pratt heard the case, noting that the pardon power “is limited, as are all powers conferred by the Constitution, by the Bill of Rights which expressly reserved to the ‘individual’ certain fundamental rights.”

The judge made clear that such arguments rarely would be successful, though. With any offer of commutation, Pratt wrote, “the convict-offeree has the choice of remaining under his judicially imposed sentence or accepting the remission of his sentence and abiding by the condition upon which it was offered. The convict cannot then ‘complain’ of the choice he has made.”

But is the president authorized to offer a conditional pardon in the first place? The pardon power, Pratt wrote, must be considered in its place “as part of our total constitutional system.”

As with most pardon questions, the short answer is yes. But, unlike in many other challenges, Pratt did suggest an outer limit — a scenario in which a conditional pardon could be found to be unconstitutional.

Examining some past instances in which courts had upheld conditions on presidential and some state commutations, Pratt laid out a two-part test for determining whether a condition attached to a commutation is permitted: (1) “the condition be directly related to the public interest,” and (2) “the condition not unreasonably infringe upon the individual committee’s constitutional freedoms.”

As to Hoffa’s conditional commutation specifically, Pratt concluded that “the condition in question was within the President’s pardoning power and that under the circumstances was reasonable and not violative of any of [Hoffa’s] constitutional rights.”

Hoffa appealed and the case very well could have reached the Supreme Court. But on July 30, 1975, Hoffa famously disappeared, the case became moot, and the constitutional question raised by his case remains an open one.

(A 1998 Supreme Court case, addressing state clemency procedures, acknowledged that there could be circumstances in which state procedures failed to meet due process guarantees, but the case did not directly address presidential pardons, let alone the sort of questions at issue regarding presidential pardon conditions.)

The Iran-Contra Pardons

Enter Iran-Contra — the presidential scandal concerning secret weapon sales during the second term of President Reagan’s administration, during which George H.W. Bush served as vice president. The sales and subsequent cover-up led to congressional and criminal investigations that continued on into Bush’s presidency.

After losing re-election in 1992, however, Bush issued a series of pardons to those implicated in and some convicted of crimes relating to the Iran-Contra scandal, including, most notably, former Defense Secretary Caspar W. Weinberger (who faced trial over allegations that he lied to Congress about the sales).

“[N]ot since President Gerald R. Ford granted clemency to former President Richard M. Nixon for possible crimes in Watergate,” the New York Times wrote at the time, “has a Presidential pardon so pointedly raised the issue of whether the President was trying to shield officials for political purposes.”

Bush pardoned Elliott Abrams, who had pleaded guilty to “willful failure to answer questions pertinent to a Congressional inquiry,” in December 1992. As the US Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit put it when reviewing his case in 1997, “Abrams deceived three Congressional committees” and “has admitted that he deceived at least two of them.” Following his guilty plea, the DC Bar sought to suspend Abrams’ law license for a year.

With Bush’s pardon in hand, however, Abrams argued that “the President's action blotted out not only his convictions but also the underlying conduct.” Whether pardons erase the underlying conduct or just the conviction (or possible prosecution) itself is hotly disputed due to some language in early pardon cases. A key 1866 Supreme Court decision noted that a pardon “makes him, as it were, a new man, and gives him a new credit and capacity” — language that has often been used since by those seeking broad effects of presidential pardons.

The DC Circuit, however, sided with the majority of other courts to examine the matter, calling “[t]he implications of Abrams' position … troubling to say the least.” They questioned whether a pardon could then be used, for example, to prevent medical licensing boards from considering the underlying conduct of a pardoned doctor who had, while drunk or high, caused death or serious injury to patients.

“The proposition that the alcoholic but pardoned surgeon (or, by analogy, a habitually inebriated and unsafe airline pilot) cannot be disciplined is, in our view, altogether unacceptable and even irrational, and it has been emphatically rejected by the courts,” the court held.

These are basically questions about how other parts of society can receive a pardon and how a pardon works in real life — whether the pardoning of a conviction then erases what preceded the conviction, and whether civil society can still make decisions based on what preceded the conviction.

The Supreme Court has not definitively resolved the matter. But the DC Circuit — and most courts — have taken the view, expressed in 1995 by then-Assistant Attorney General for the Office of Legal Counsel Walter Dellinger, that “[d]iscipline associated with the breach of the conditions of a professional license, where the disciplinary action is not triggered merely by the fact of commission or conviction of a federal offense, generally would not be barred by a pardon.”

Of course, even that is — again — not so much a limit on the president’s power as it is a limit on the effects of a president’s pardon outside of the criminal justice system.

The Bottom Line

The founders — as subsequently described by Chief Justice William Howard Taft — put forth impeachment as the main check on a president’s abuse of the pardon power. Outside of amending the Constitution itself, that means there is very little traditional recourse in the legislative and judicial branches for perceived misuses of that power.

Congress tried to limit that power after the Civil War. Lower federal courts tried during Prohibition. Other questions have arisen over time. But, in the end, the president has enormous power to grant pardons for all federal offenses — even if they can come with, in the case of Gerald Ford and Richard Nixon, enormous political consequences.

The limits on pardon power largely concern how pardons work for the pardoned, such as whether they can reclaim property lost as a result of their crime or whether civil society may consider whatever actions preceded the pardon in making some kinds of decisions.

The legal history isn’t always clear and the Supreme Court hasn’t ruled definitively on some of the most fraught questions (like whether a president may pardon himself). But if American history so far is any indication, the answer is almost always: Yes, he can do that. ●