"Some people only remember back to the wave that woke them up."

Evan Wolfson sat in his Manhattan office less than a week before the Supreme Court's landmark hearings on same-sex couples' marriage rights — a cause to which he has devoted most of his adult life, beginning with the formative 1983 paper he wrote on the subject while in Harvard Law School.

With Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King Jr. looking down at him from pictures on the wall, Wolfson — a balding, professorial man who speaks quickly in paragraphs that contain many commas but few periods — had no doubt about his influences, or about the moral strength of his cause. Now, 30 years after he started this fight, he marvels at how marriage equality — once a marginalized, abstract notion that seemed absurd in all corners of society — has come within a gavel's strike of being the law of the land.

"By historical standards, this has gone very quickly. Even if you remember that it didn't happen in the last 10 minutes, it has gone very quickly," Wolfson said. He launched Freedom to Marry in 2003 in an attempt to move beyond the existing legal groups and provide an educational and political effort solely devoted to advancing the cause of marriage equality. "It's gone very quickly because of the power of marriage and because of the absence of any really good reason for excluding couples," he said.

Wolfson wasn't the first person to call for marriage equality. Indeed, the first wave began moving in the aftermath of the 1969 Stonewall riots that gave birth to the modern LGBT civil rights movement. At the time, the courts pushed back strongly. A Kentucky Court of Appeals judge put the general view of the courts most bluntly in 1973 when he wrote that Kentucky couldn't grant a marriage license to a same-sex couple because "what they propose is not a marriage," and the U.S. Supreme Court rejected a similar claim a year earlier as lacking "a substantial federal question."

Since the 1980s, though, Wolfson and his unlikely compatriot in the cause — the self-identified conservative-libertarian writer Andrew Sullivan — have been arguing forcefully and persuasively that achieving marriage equality is the key step to advancing gay rights in society. Although neither will be talking to the justices this week, their writings — and lives' work — echo throughout the arguments that have resulted in successful court decisions and unprecedented public support for their once-novel proposal.

While a Harvard Law School student in April 1983, Wolfson, just 26 at the time, authored "Samesex Marriage and Morality: The Human Rights Vision of the Constitution." Although it is certainly not the same language he would use today at Freedom to Marry, many of the arguments and themes are remarkably resonant.

"By abolishing sexualist discrimination and permitting full and equal self-expression on the part of all lovers for all beloveds … we will create a society more safely and richly founded on our individual freedom and equality. Such a society, where people are equally free to love and choose according to the dictates of their heart, best promotes the just and moral pursuit of happiness," Wolfson wrote.

At 56, watching history take place before his eyes, he doesn't speak all that differently. Marriage equality "will vastly further the integration of gay people and our loved ones into the larger society, the fabric of society, the fabric of family," he said. "And it will lighten the load of sexism and gender expectations that everyone carries. It won't eliminate it, but it will further people in the right direction."

By taking up the issue in the '80s, Wolfson put himself in a small minority — even within gay-rights circles, where advocates were more focused on workplace discrimination, AIDS issues and hate crimes than on marriage rights. But it wasn't too long before he won key support from an unexpected ally on the political right.

On Aug. 28, 1989, a conservative British writer at The New Republic, Andrew Sullivan, 26 at the time, authored a cover story, "Here Comes the Groom," outlining the conservative case for marriage equality.

"Legal gay marriage could … help bridge the gulf often found between gays and their parents. It could bring the essence of gay life — a gay couple — into the heart of the traditional straight family in a way the family can most understand and the gay offspring can most easily acknowledge. It could do as much to heal the gay-straight rift as any amount of gay rights legislation," he wrote.

For some gay rights advocates, the first "wave" to wake them up came in 1993, when a Hawaii Supreme Court ruling appeared to set the state on a path that could lead to marriage equality. But the ruling enflamed the culture wars and awoke the federal government. In 1996, the Republican-led Congress rushed DOMA through both chambers with support from Democratic President Bill Clinton — enshrining the notion that marriage is between a man and a woman in federal law.

For other advocates, it wasn't until the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled in favor of same-sex couples 10 years ago in a case brought by Gay & Lesbian Advocates & Defenders' Mary Bonauto that the marriage movement became a real part of the political and legal debate. Even more recently, the marriage debate began in earnest when California's voters ended same-sex couples' marriage rights with the passage of Proposition 8 in November 2008. As 2009 began, a unanimous Iowa Supreme Court ruled in favor of marriage equality and several New England legislatures passed marriage equality measures.

The four years since, all parties engaged on the issue agree, have been a tidal wave of action — one that reaches the steps of the Supreme Court Tuesday morning.

Nearly 25 years after his New Republic cover story, talking with Sullivan at a coffee shop a few blocks from where the Stonewall riots took place in 1969, his argument has not changed much. In the nine states that now allow marriage for gay couples, plus the District of Columbia, Sullivan said something profound is happening.

"What this means, is you're marrying into another family, so the family has to own the gay member, then they have to own the gay marriage as a marriage like the other marriages in the family," Sullivan said. "And that total absence of a distinction is incredibly empowering for the gay people who go through it."

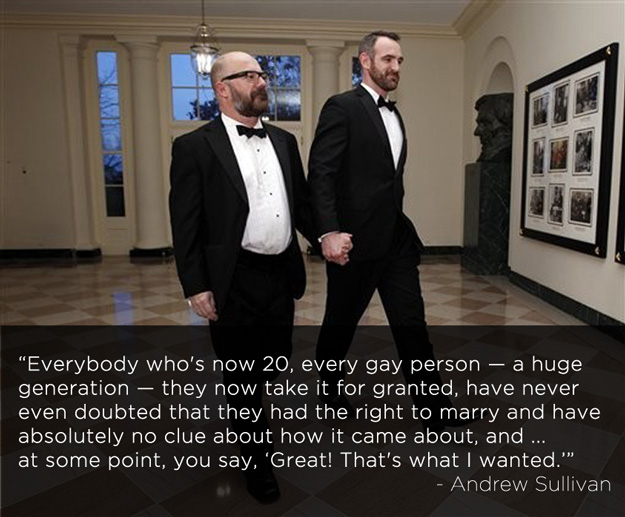

The famously bearded Sullivan is grizzled — looking ever more like a wizard, his mother tells him — and he is hard at work, having just finished a post for his highly trafficked blog, The Dish, before beginning to talk about the long fight he and Wolfson have helped to lead to advance marriage equality.

Long before Ted Olson and David Boies teamed up to take on Proposition 8, Wolfson and Sullivan were the original "odd couple" of the marriage equality movement.

The issue, unexpectedly for both Sullivan and Wolfson, also has become personal. Both men now wear a wedding ring. Sullivan married Aaron Tone in Massachusetts in 2007, and Wolfson married Cheng He in New York in 2011.

"As I often say, I was a victim of my own arguments," Sullivan said. "But it wasn't an argument that got me there. It was just meeting this one person. It really was."

Sullivan met his now-husband nine years ago at a gay circuit party — "which is not exactly where you think traditional marriage begins: semi-naked on the dance floor at 4 a.m. in the morning," he joked.

Looking at his phone, which occasionally lights up with a text message from his husband, Sullivan added, "But, we just said good-bye, he's walking the dogs, and we're still living together and sharing our lives together."

"Even me, I was shocked," Sullivan said of the experience of getting married. "I think there were two moments in my life when I was really shocked by the way I felt. The first was how much shame I felt when I found out I was HIV positive. And the second was how much joy I felt when I got married. I didn't anticipate either of those things. And that's the arc. That's what we're really talking about. We're talking about the human heart here, and its ability to heal."

Wolfson described a similar shock about his marriage.

"I was never really in this because of my own personal desire to get married. To me this was always … about, number one, what was right in terms of the American values of liberty and justice and equality and freedom and the pursuit of happiness, and secondly, because it would be an engine of change. It would help transform people's understanding of who gay people are."

"But, once I met the love of my life," Wolfson says of Cheng He, who he told The New York Times he first encountered on the dating website gay.com, "I, like many others, got to experience … the true power of marriage and, within the power of marriage, the power of the wedding."

It's more than that, though, he says. "It's also the power of the wedding vocabulary and the wedding conversation and how everybody wants to talk to you about your wedding. And they want to celebrate your wedding, and they want to read about your wedding in The New York Times. And they want to tell you how your wedding should have been arranged differently," he laughs.

Sullivan echoed that, saying, "My role was always a little weird at Christmas. I was like, 'Aaron's boyfriend, whatever.' … But when they found out we were engaged to be married, it all changed. They suddenly had a vocabulary, a linguistic architecture to put me in. I was a fiancé. 'Oh, now I know who you are. Now I know what your relationship to my son is. Now I know what to expect from you. And you better show up for Christmas.'"

He looked up and smiled. "Even though I can't stand Christmas, and Christmas in Detroit is not a fate I would wish on anyone. But that's the price of gay marriage. It's OK, Aaron had to go to my sister's 50th in snowy England last year."

Wolfson said that's one of the primary changes that comes about through marriage equality.

"When you ask what's going on here, that's what's going on here," he said. "That broke the back of anti-gay prejudice and discomfort, and it helped us move from a movement goal of wanting to be let alone to wanting to be let in. And we're in."

Wolfson pointed to President Barack Obama lending his personal support to marriage equality in May 2012 as a defining moment.

"'From Seneca Falls to Selma to Stonewall,'" Wolfson said, quoting from Obama's second inaugural address. "When the president embraced the freedom to marry, exalted the freedom to marry in the inaugural address as a central part of the American project, what he was saying was, 'This is not only something that matters to gay people. This says something about who we are, as Americans, and about what kind of person each one of us is in how we treat others.' And, having achieved that, we're winning, because most people are, and want to be, and rise to be, fair."

Throughout much of the past three decades, Wolfson, Sullivan, and others were defending themselves against opposition from the right — but also questions from members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender community about whether the cause of marriage should receive the attention and energy it's been given. But Wolfson said the marriage movement is "what it turns out people really wanted" and has driven many other important gay rights issues.

"When you look at the record of all it brought along as an engine — more nondiscrimination laws, more gender identity protections, more safe schools and other programs, more attention to gay seniors — across every front, more has been achieved in the 'marriage' chapter of our movement than in the 'let's not do marriage' chapter," he said. Acknowledging that "there are many cumulative and catalytic reasons that happened," he maintained of the marriage equality push, "I think it's very hard to argue that it's not been extraordinarily transformative."

Sullivan, meanwhile, pointed to the AIDS epidemic as having been pivotal within the LGBT community.

"This sounds awful, and I don't mean it to be awful, but it's true: The generation [of gay people] that would have most resisted this reform were dead. The people whose lives were defined by sexual liberation, that generation — understandably defined by sexual liberation, because I completely understand why that has to come first — but, by the tragedy of AIDS … we didn't have as much resistance within the gay community, for generational reasons, to this change."

And, for those who lived, Sullivan noted, "It radicalized everybody. The entire community was mobilized, even if it was just taking care of a friend. Secondly, we were also suddenly made aware of our utter nakedness, legally, in terms of protecting our loved ones. And thirdly, lesbians started having babies. So, gay deaths and lesbian births [combined] to reveal that we had nothing to defend us if we were attacked by our own families or next of kin, which was often the case. We had no rights."

Sullivan also pointed to a later, unlikely cause for advancement of his marriage aims: President George W. Bush.

"Certainly, it seems to me that the gay community was not united behind this until George Bush came out against it. I think his support for the Federal Marriage Amendment 10 years ago was the moment it become not just legit, but crucial, to support the fight. Until then, it was still a struggle," he said. "Even those who didn't disagree with us did not want it to be a priority and thought it was a distraction. Whereas I thought, and Evan definitely thought, that if we could change the culture, then eventually the laws and the court will change."

It has changed.

"Everybody who's now 20, every gay person — a huge generation — they now take it for granted," Sullivan said. They "have never even doubted that they had the right to marry and have absolutely no clue about how it came about and don't care, really, for the most part. And, at some point, you say, 'Great! That's what I wanted.' That was the goal. We wanted to make this a virtually normal thing," he said, referring to his 1995 book, Virtually Normal.

Sullivan said that after becoming HIV positive in 1993, he asked for the summer off from The New Republic in 1994 to write Virtually Normal. "I would never have written it if I hadn't thought I'd be dead in five years' time. I thought, I've got only a certain amount of time left; I want to write my best case for this and leave it behind. I think both the memory of those we lost and the liberation of knowing we had nothing left to lose … gave you a sort of freedom to say what you believed."

And he did, touring the country to make his argument for how, as he wrote in Virtually Normal, "[t]he critical measure for this politics of public equality—private freedom … is equal access to civil marriage."

Wolfson also said what he believed, leaving his senior role at Lambda Legal in 2001 to launch Freedom to Marry. When same-sex couples began to marry in Massachusetts in 2004, Gallup's polling showed that 54% of Americans believed "gay or lesbian relations [we]re morally wrong" and 42% believed they were "morally acceptable." Wolfson's aim was to change that.

After Massachusetts, Wolfson said it was "somewhat surprising that it took us as long after the wins in Canada and Massachusetts to get the second one."

In the 2004 elections, voters in 11 states amended their constitutions to ban same-sex couples from marrying. Some states went further, banning civil unions or other relationships from being recognized. Although Sullivan and others have regularly characterized the votes as a backlash, Wolfson was defensive on the point, saying, "I don't like the word 'backlash.' I never think of it as a backlash. We're the ones trying to overturn oppression; we didn't trigger oppression." Of the votes, he said, "That was an orchestrated political attack, done for political purposes that were exploitative."

It wasn't until the California Supreme Court ruling in 2008 that a second state followed Massachusetts. In October 2008, the Connecticut Supreme Court followed suit. In November of that year, however, the initiative effort, Proposition 8, ended marriage equality in California. The next year, a new organization, the American Foundation for Equal Rights, sued in federal court with a claim that the initiative violated the U.S. Constitution. Gay & Lesbian Advocates & Defenders filed a similar lawsuit, challenging the federal marriage definition in DOMA, earlier in the year. Lambda Legal and the American Civil Liberties Union followed up with DOMA challenges of their own.

In 2012, when voters in three states — Maine, Maryland, and Washington — voted in favor of allowing same-sex couples to marry, the Gallup polling numbers had flipped from 2004, with 54% of people saying "gay or lesbian relations are morally acceptable" and 42% responding that they are "morally wrong."

Days before the justices consider the arguments that Wolfson first made 30 years ago, both him and Sullivan were considering the moment.

Remembering the way he felt when he first realized he didn't see marriage to a woman in his future, Sullivan said, "The only structure I knew was my family. And my church. And that when you grow up, you get married. So, for me, all I saw was darkness ahead. I saw no achievable future. I didn't know what being gay meant, but I knew I couldn't be part of my family."

Now, he said, it's different. "Just the concept of there being marriage for gay people, just the idea of it in the culture, will trickle down, through the media and through the culture, reach the next generation of 7-year-olds, and they will get a signal that they don't face blackness. They can get married. Even if they don't want to go that way, it provides a structure to channel or even frame your emotional life, your sexual life."

As they both noted, the timing also is key — in having found the right wave.

"I think we should all feel very lucky because we could have been doing all this work, and endured all we've had to endure … the work we've all done, the conversations we've all had, the patience we've had to show, the tenacity we've had to show," Wolfson said.

"We could have been doing all of that, and doing all of it right, and it not being the right time and it not coming to fruition. Instead, we are, I unquestionably believe, the lucky ones who are going to live to see this. That's a really lucky joy to have, to have made the world better, and to have done the right thing, and helped others get to the right place, and get our country to the right place — and moved the world in the right direction."