WASHINGTON — In a 6-2 decision, the Supreme Court held Thursday that the federal government cannot force groups that get government HIV/AIDS-prevention funding to pledge their opposition to prostitution, a decision based on the groups' First Amendment rights and the limits of government power when it gives money to outside groups.

The case involved grants given to nongovernmental organizations under the United States Leadership Against HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria Act of 2003, called the "Leadership Act." The law required not only that no federal funding "promote or advocate the legalization or practice of prostitution or sex trafficking," but also that groups receiving funding have "a policy explicitly opposing prostitution and sex trafficking."

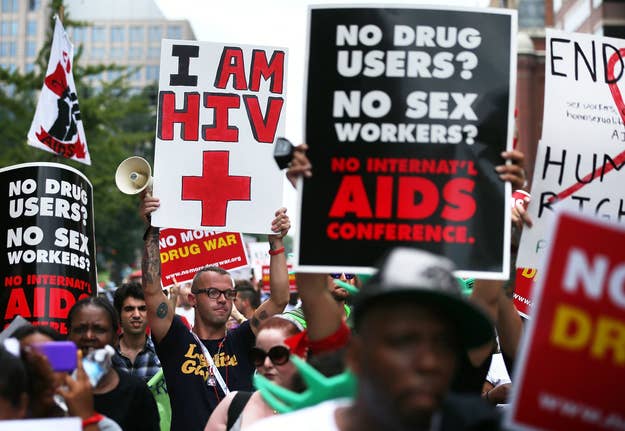

It was this second part of the program — the "Policy Requirement" — that several organizations challenged and that the Supreme Court struck down as unconstitutional on Thursday. They told the justices that they feared the requirement could "diminish the effectiveness of some of their programs by making it more difficult to work with prostitutes in the fight against HIV/AIDS" and force them to censor their discussions, even in programs or at events where no federal funds were being used.

Chief Justice John Roberts wrote the court's opinion for himself and several of the more moderate-to-liberal members of the court, and Justice Samuel Alito, siding with more protection given for First Amendment rights in a regularly recurring question about how much control government has over what a group can say when accepting government funds.

They concluded that, while government has broad authority to set conditions defining a federal program, it cannot ban protected-speech activity outside the scope of that federally funded program. Justice Elena Kagan did not participate in the consideration of the case because of her prior role as the top appellate lawyer in the Obama administration, which was defending the law in question.

Describing the difference between allowed conditions and unconstitutional ones, Roberts wrote for the court, "[T]he relevant distinction that has emerged from our cases is between conditions that define the limits of the government spending program—those that specify the activities Congress wants to subsidize—and conditions that seek to leverage funding to regulate speech outside the contours of the program itself."

Although he acknowledged that the difference between the two "is not always self-evident," he concluded, "Here, however, we are confident that the Policy Requirement falls on the unconstitutional side of the line."

Justice Antonin Scalia, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, disagreed with this formulation, writing in dissent that this was clearly permissible because there is no coercion and the condition is simply an example of "government ... enlist[ing] the assistance of those who believe in its ideas to carry them to fruition."

"That seems to me a matter of the most common common sense," he wrote. Scalia went on to call the requirement struck down by the justices the "reasonable price of admission to a limited government-spending program that each organization remains free to accept or reject."