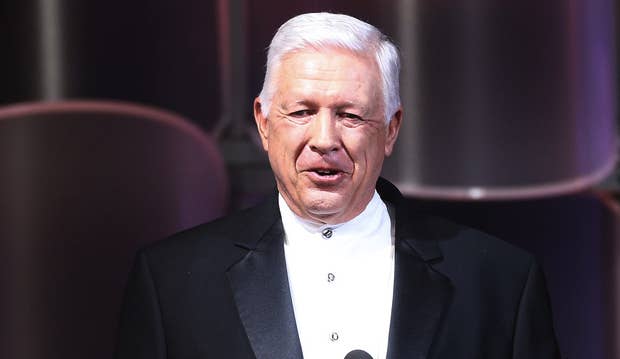

NATIONAL HARBOR, Md. — The mega-donor Foster Friess is best known as the moneyman behind Rick Santorum's socially conservative presidential campaign, the self-described born-again Christian takes a far more moderate position than his candidate on gay issues — because, he said, of a personal connection, his gay brother-in-law.

"When you talk about the party, that's the problem because there isn't any unified message," Friess said of the Republican Party's position on gay issues Thursday in an interview at the Conservative Political Action Conference Thursday. "You've got people who are gay-bashers, who forget that these are human beings that need love just like all of us need love. We have to be sensitive to that."

As with many conservatives who profess a level of support for gay rights, Friess first focused on the international scene for his attention.

"I've said before, the number one thing that we have to work on is protecting the gay community from sharia law. Now, in the United States, it's probably not a big issue right now, but my brother-in-law is gay and his partner and I would like them to be able to travel any place in the world without them risking harm," Friess said. "In Iran, they basically hang them or behead them. So, my number one issue is: How do we support them and rally behind the gay community to make sure it's safe for them, just, to live?"

Looking inside the United States, he said, "I think culture precedes politics, and I think the attempts to try and legislate people's behavior ... isn't going to be productive until the culture decides what they want to achieve.

He did single out one domestic issue — a consequence of the Defense of Marriage Act's prohibition on federal recognition of same-sex couples' marriages: "I think it's unfair that people can't give assets to whoever they want. When I die, my assets can go to my wife. And a gay person — you ought to have a system where maybe you can just say, 'You can give your assets to anybody you want.'"

Although his solution isn't the same sought by Edith Windsor in her challenge to DOMA that is before the Supreme Court, Friess raised the issue as one of fairness. He also connected it to other issues, which he characterized as more significant harms to marriage than would allowing same-sex couples to marry.

"I think it ties into the other problem: We have to be concerned about heterosexual marriage," Friess said. "We have now 60-70 percent of Hispanics and blacks born out of wedlock. And, with Caucasians, it's 30 percent. So, the whole idea of — 'How do we encourage fatherhood? If they father a child, what's their responsibility to that child?' — I think that is probably a much bigger issue than any of the other issue that we might deal with in terms of the sexual realm or the whole idea of relationships."

Friess hedged on whether those views mean DOMA should be struck down when the Supreme Court considers its constitutionality this spring.

"I'm not a lawyer. I don't know what's going on. I just know that the people that I meet who are gay, including my brother-in-law and his partner, and my wife is very active in the art community, and we meet a lot of people that are gay, I think, number one, it's our responsibility to love them. That's the bottom line," he said.

"I don't get so involved in the technical aspects of the marriage issue," Friess said. "It's just perplexing for all of us. Just, the bottom line is: How do we reduce the divisiveness?"

Echoing others at CPAC who seem intent on moving the party away from an anti-gay position yet who likewise aren't prepared to fully embrace marriage equality as a right, he pointed to religious liberty concerns.

"I think there's a certain amount of this gay issue that is a religious liberty issue. I was talking with a very, very prominent gay person whose name I won't mention. He said, 'Look, I lost my partner a year ago, and I still wear the ring of commitment that cherishes our relationship we had, but churches ought to have the right to believe what they believe,'" Friess relayed. "If we really want to cherish religious freedom, people who want to believe that same-sex marriage should take place, they have a right to believe that, and people who want to believe it's inappropriate, we should not demonize those people — if we really believe in religious liberty."