WASHINGTON — Cortez Davis is serving life in prison under Michigan’s felony murder statute for a killing that occurred when he was 16 years old. Davis was not the gunman, the trial judge in his case found, but was a participant in a robbery when the fatal shooting took place.

Nonetheless, under the Michigan law, because he was a key participant in the underlying felony, he was charged with felony murder. Davis was sentenced to life without the possibility of parole — the mandatory sentence in the mid-1990s.

More than a year ago, lawyers for Davis asked the Supreme Court to take up their client’s challenge to a lower court decision that upheld that sentence.

Now, following a recent Supreme Court decision, his challenge and several others are likely to be sent back to lower courts — a move that could, depending on what state courts do next, put off even further the chance people like Davis have to reduce or end sentences the court has repeatedly thrown into question in recent years.

The petitions ask the justices to address how and under what circumstances states can sentence juveniles to life without parole, including in a handful of cases in which the convictions are for felony murder.

Over the past decade, the court has taken up several cases addressing juvenile justice issues. The court ended the eligibility of juveniles for the death penalty in 2005, and has since, in a series of rulings, narrowed the eligibility of juveniles for life sentences.

Last week, the court handed down yet another significant ruling on juvenile sentencing — this one in the case of Henry Montgomery — that deals with complicated legal issues, but has major consequences.

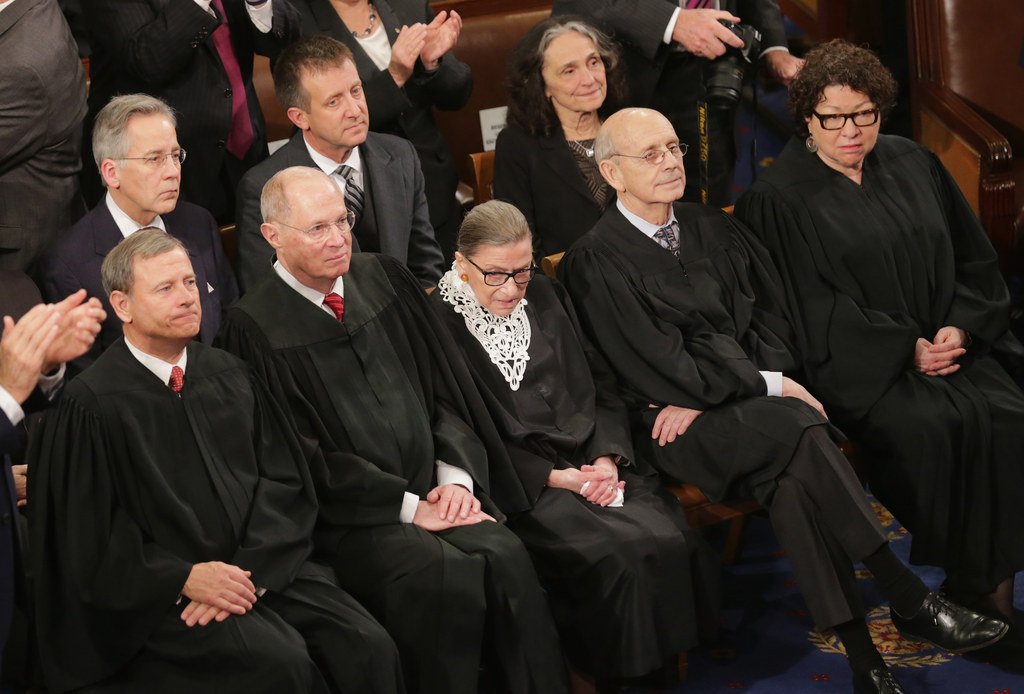

The court, in an opinion by Justice Anthony Kennedy, held that the 2012 ban on sentences of mandatory juvenile life in prison without the possibility of parole applied not just going forward, but also to those sentenced in the past like Montgomery. Montgomery is in jail for a killing he committed at 17 in 1963.

The ruling from the high court resolves a dispute among lower courts: Some had decided that a 2012 ruling from the high court was a procedural ruling that only applied to new sentences. The Supreme Court now says that isn’t the case.

“In light of what this Court has said in [past cases] about how children are constitutionally different from adults in their level of culpability … prisoners like Montgomery must be given the opportunity to show their crime did not reflect irreparable corruption; and, if it did not, their hope for some years of life outside prison walls must be restored,” Kennedy wrote in the Jan. 25 decision in Montgomery v. Louisiana.

Far from a narrow procedural ruling, Kennedy explained that the 2012 ruling — Miller v. Alabama — was a substantive one, and, in its wake, “it will be the rare juvenile offender who can receive that same sentence.”

While Montgomery’s case was pending, however, the court left several related cases like Davis’s one — all of which ask the court to go further down this path — waiting for action from the justices.

"[P]risoners like Montgomery must be given the opportunity to show their crime did not reflect irreparable corruption."

Most expect the justices now to send those cases back to lower courts to consider how the Montgomery decision affects their respective cases. During that period, how state courts interpret the Supreme Court’s ruling could vary widely. How rare is the “rare juvenile” that Kennedy writes about whose crime reflects “irreparable corruption”? How do states make that determination?

The court sending back Davis’s case would mean a further series of court hearings and rulings — all of which could lead to his eligibility for parole, but, if past experience is any guide, it just as likely will lead him back to seeking review, yet again, from the Supreme Court.

For Davis, this has been going on since 1994. The life without parole sentence that he is serving — and has served now for more than 20 years — was imposed by an appeals court over the objections of the trial court judge, who initially sentenced him to 10 to 40 years.

After the Miller Supreme Court ruling, the trial judge found that the ruling should apply to past offenders like Davis and that he was, as such, entitled to re-sentencing. “We, the People of the State of Michigan have treated this juvenile, now man, inhumanely,” the judge wrote.

A little more than a month later, though, that decision was reversed by the appeals court — a decision later upheld by the Michigan Supreme Court.

In January 2015, Davis asked the Supreme Court to review his case. In addition to asking the justices to review whether the ruling barring mandatory life without parole sentence applied to past offenders like him, Davis’s lawyers — led by the Equal Justice Initiative’s Bryan Stevenson — also asked the court to decide whether life without parole sentences, mandatory or otherwise, should be held to be unconstitutional for people like Davis who were juveniles at the time of their crime and who the trial court concluded neither killed anyone nor intended to do so. (An earlier Supreme Court ruling in 2010, in Graham v. Florida, barred life without parole for non-homicide offenses committed by juveniles. This second question in Davis’s case, effectively, asks the court to rule that felony murder is included in that bar.)

After initially being scheduled to be reviewed by the justices at their private conference in early March 2015, Davis’s case was rescheduled to be considered in April.

In the meantime, though, the court agreed to hear Montgomery’s case out of Louisiana. Montgomery similarly was sentenced to life without parole under a statute that made the punishment mandatory. Montgomery, however, was convicted for the murder of a police officer that he himself had committed more than 50 years ago. The only question in Montgomery’s case, therefore, was whether the court’s earlier decision ending mandatory life without parole for juveniles should apply to past offenders.

Although the court docket in Davis’s case shows that the court was to consider his petition for review in April and again in May of this past year, the justices are yet to act on it. In the meantime, Davis has continued serving his sentence.

On Jan. 25, Kennedy detailed the court’s decision that Louisiana had to give retroactive effect to the Supreme Court’s 2012 decision in the Miller. In the wake of that decision, it’s likely that the justices will send Davis’s case back to the Michigan Supreme Court to reconsider it. As Kennedy suggested in the Montgomery decision, Michigan either could re-sentence Davis — considering whether his crime reflects “permanent incorrigibility” — or make him eligible for parole consideration.

If Davis is re-sentenced instead of being granted a chance at parole, however, and if he is sentenced to life again, then he likely would go back to the U.S. Supreme Court — asking the court, again, to hear his case on the felony murder question. (As is already being seen in Montgomery’s case, state officials in Louisiana have told the state's supreme court that their aim is to re-sentence those with mandatory life without parole sentences, rather than give them the possibility of parole.)

At that point, even if the justices did take up his case, Davis likely would have served another two, three, or more years serving a sentence that could be held to have been unconstitutional based on Supreme Court rulings from 2010, 2012, and 2016 — and would only get the constitutional relief he has been seeking whenever his hypothetical case is decided.

Davis is by no means alone. Several similar cert petitions addressing juvenile life sentences have been pending for some time.

Donte Lamar Jones was sentenced to life without the possibility of parole in Virginia for shooting a woman, who later died, during a robbery in 2000 when he was 17. In April 2015, he asked the justices to review his case. In addition to asking them to resolve whether Miller is retroactive, his lawyers, led by Duke McCall III of Morgan Lewis & Bockius, also asked the court to resolve whether Miller even applies to sentences like those given to Jones. The Virginia Supreme Court ruled that it does not, because judges in Virginia can suspend a statutorily required sentence like that given to Jones. As such, they reasoned, it is not actually mandatory.

Lawrence Jacobs was sentenced to two consecutive life sentences without the possibility of parole for felony murder, called second degree felony murder in Louisiana, in a burglary committed at 16 in which his co-conspirator killed the two people at the house they were robbing in 1996. In June 2015, he asked the justices to review his case. Like Davis, Lawrence has asked the court to review whether a juvenile can be sentenced to life without parole when he neither killed nor intended to kill anyone. Additionally, though, his lawyers, led by Ben Cohen of the Promise of Justice Initiative, have posed a more broad question: whether any life sentence without the possibility of parole for juveniles is unconstitutional.

Robert Cameron Houston committed a homicide at 17 and was sentenced to life without the possibility of parole in Utah. In November 2015, he asked the Supreme Court to review his case, taking up the broad question of whether life without the possibility of parole should be held to be unconstitutional for juveniles. His lawyers, led by University of Utah law professor Michael Teter, also asked the court to take up his case to answer whether the requirement in Miller that “sentencers consider an offender’s youth and attendant characteristics” before finding that a life sentence without parole is appropriate is the type of decision that other Supreme Court cases have said must be made by a jury.

The court could, and most court watchers think likely will, send all four cases back to the respective state courts for further consideration in light of the decision in Montgomery — a move that would put off any decision on the related issues.

"Th[e] question will need to be resolved by this Court, as states continue to sentence juveniles convicted of felony murder to life without parole."

However, while the justices could send back those specific cases, the issues themselves will keep making their way to the Supreme Court.

On Tuesday, eight days after the Montgomery decision was handed down, the law professor who submitted the petition in Houston’s case submitted a new cert petition — in a different case of a juvenile sentenced to life without parole.

“Albert Bell has spent the last 23 years incarcerated for his role in a robbery that ended in two deaths because of another's acts,” Teter told the justices of the crime Bell committed at 16.

Despite the 2010 decision ending juvenile life without the possibility of parole for non-homicide offenses and despite the 2012 decision ending mandatory juvenile life without the possibility of parole for homicide offenses, Teter explained, the court has not resolved where felony murder falls.

Unlike in several of the earlier filed petitions, the case does not raise the questions about Miller retroactivity, so sending Bell’s case back to be reconsidered in light of Montgomery would not appear to be an option for the justices. They either need to accept the case (or one of the earlier filed ones) or deny it, a move that would leave in place the Arkansas Supreme Court ruling upholding Bell's life without parole sentence for felony murder.

“That question will need to be resolved by this Court, as states continue to sentence juveniles convicted of felony murder to life without parole,” Teter stated.