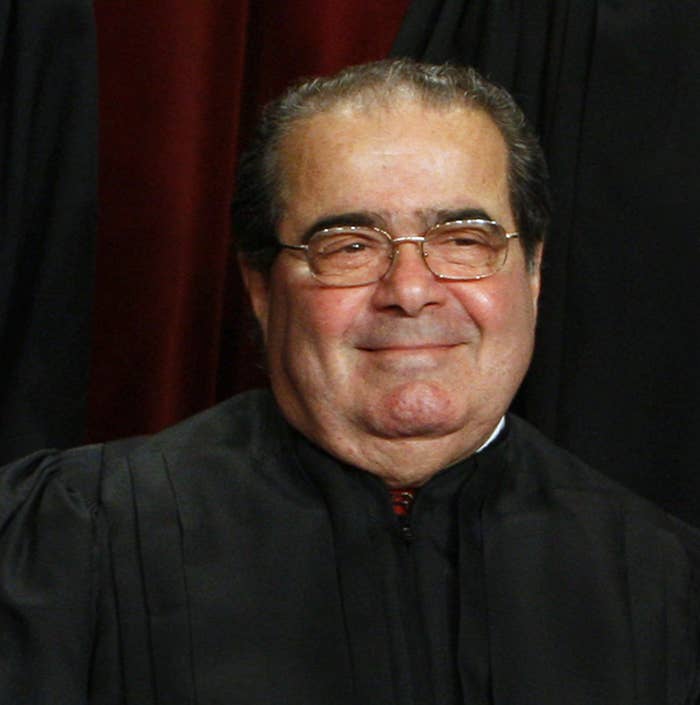

On Saturday, the legal and political worlds were upended when news came from Texas that Justice Antonin Scalia — the firebrand whose voice controlled the conservative legal movement for decades — was found dead.

Scalia, 79, had been a fixture on the court since October of 1986, when he took his seat on the bench after being nominated by President Reagan and approved by the Senate on a 98-0 vote.

Scalia's departure from the court has the potential to move the court significantly to the left for the first time in President Obama's presidency. While Obama already has made two appointments to the bench — and even though both of those were replacing justices appointed by Republican presidents — both of those justices had, by the time of their retirement, been consistently voting with the more liberal bloc of the court.

Now, however, the vacancy left by Scalia's death is a seat held by one of the most forceful conservative voices on the court for the past 30 years.

The unexpected vacancy raises many questions — immediately shifting the bedrock at the Supreme Court, setting up an intense battle between the White House and the Senate leadership, and changing the presidential campaign overnight.

So, what's going on with the Supreme Court, and what happens next?

The Supreme Court:

What happens to the Supreme Court's normal work?

The Supreme Court will continue to function with eight justices for the time being.

What happens to cases where the judges have heard arguments but haven't issued a decision?

There are 24 cases in which the justices had granted certiorari (agreed to hear a case) and held arguments but have not yet handed down a decision.

The justices vote on cases in a private conference shortly after arguments, in order to decide what the majority view of the court is and who should draft the opinion of the court. The vote, however, is only tentative: Justices can and do sometimes change their votes up to the days before a decision is handed down.

Scalia's votes in these 24 cases are now gone; there are only eight justices (or seven, if a justice already had recused herself or himself, as happened in one major case still pending) who will be deciding these cases as of now.

Since most Supreme Court cases aren't closely divided decisions, it's expected that Scalia's death won't change the outcome in most of those 24 cases.

There are two ways, though, in which they will change things — one of which is the most dramatic, immediate effect of Scalia's death.

What happens if the court voted 5-4, but hadn't issued an opinion yet, and Scalia was in the majority?

If the initial vote had been 5-4 and Scalia was in the majority, the court is now evenly divided 4-4. A tie vote on the Supreme Court, effectively, allows the lower court ruling that was being appealed to stand. But this scenario creates no national ruling like one from the Supreme Court does.

In some instances, when less than a full court was to decide an issue, the court has ordered cases for reaurgument in the next term. As a 2003 article on Supreme Court reargument notes, "there is no specific rule governing" reargument. The authors go on to add that "the practical norm governing reargument" is that reargument is ordered when a member of the court's majority requests reargument and that a majority of the justices agree.

Finally, the court could make a procedural or technical ruling — something that could get the support of a majority of the justices, and avoid a decision on the constitutional or statutory issue. An example of this would be when the Supreme Court dismissed the challenge to California's Prop 8 marriage amendment on standing grounds, holding that the supporters of Prop 8 didn't have the authority to bring the appeal.

What important cases had arguments heard but no decision yet? In other words, what major cases that are in progress could be affected by Scalia's death?

There are at least four major cases where Scalia's vote may have been important to the outcome of the decision.

A public union case: In this case, Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, the court appeared to be tilted 5-4 against the unions. Now, it's 4-4. Because the lower court — the generally liberal 9th Circuit Court of Appeals — had sided with the unions, a 4-4 decision would mean that public unions would continue to be free to collect fees from nonunion members, called "agency fees."

Two voting rights cases: One concerns how population is considered for redistricting; another concerns how much partisanship is allowed in redistricting

An affirmative action case: This case is already being heard for a second time, over the affirmative action admissions plan at the University of Texas at Austin. (The affirmative action case was already one justice short, as Justice Elena Kagan had recused herself from participating due to her involvement in the case when she worked in the Obama administration.)

So, do we know what the Supreme Court will do with this term's close cases?

We don't know.

Linda Greenhouse wrote in the New York Times in 1985 that when Justice Lewis Powell had been out for prostate cancer surgery and recovery for a period, the court issued several 4-4 decisions — but also ordered several other cases for reargument. "If there was any principle at work here that determined which cases to preserve for reargument and which to terminate, it was neither explained nor apparent," she wrote at the time.

SCOTUSblog's Tom Goldstein pointed to what happened after the 1954 death of Justice Robert Jackson as evidence that he expects reargument in close cases. Even in that example though, Goldstein notes that three cases were set for reargument but one was decided with the court evenly divided 4-4.

As with much of the Supreme Court's internal procedures, however, the public tends to find out how the court is dealing with an unclear issue when it decides the issue by handing down decisions or orders.

What happens to the opinions Scalia was supposed to write?

If Scalia had been writing the majority opinion in the case, it will have to be reassigned to another justice. If he was in the majority, Chief Justice John Roberts decides who writes. If he was not, the most senior justice in the majority decides. All of Scalia's majority opinions were assigned to him either by the chief justice or by himself, as Scalia was the most senior justice on the court. What will happen now: Either the chief justice or the new most senior justice in the majority — likely Justice Anthony Kennedy, but possibly Justices Clarence Thomas or Ruth Bader Ginsburg — will reassign the majority opinion, but the ultimate outcome of the case is unlikely to change.

What happens to the major cases that haven't had oral arguments yet?

There are still two major cases in which the court has granted cert but has not yet heard arguments: the challenge to Texas's abortion provider restrictions and the challenge brought by several states to Obama's immigration executive actions.

Those arguments are expected to go forward as planned, but Scalia's absence could have a dramatic effect on both cases. Both cases come out of the more conservative 5th Circuit Court of Appeals, and 4-4 split decisions would let conservative decisions — upholding the abortion restrictions and striking down the immigration actions — stand. But, as discussed above, the cases also could be ordered for reargument.

(It should be noted that the court previously put the 5th Circuit's decision that upheld the abortion provider restrictions on hold, meaning that five justices already have signaled that think there's a strong likelihood that the restrictions are unconstitutional. Scalia had opposed that request, meaning his death leaves only three justices on the court opposed.)

What happens with new cases this year? The court's next term starts in October of this year. Will the Supreme Court accept new cases now for that term?

It only takes four justices to take a case. That often presents a kind of game theory regarding the potential outcome of the case: Why would four justices ask the court to take a case to decide an issue if they know the other five justices oppose their preferred outcome?

Now, though, there are only eight justices in the mix and the eight don't know who their next colleague will be — let alone when that person will be joining the court. With many petitions pending — in other words, many potential cases — the question now is how aggressive the justices will be about pushing to bring their issue up for argument.

The justices are scheduled to meet on Feb. 19 for their first conference since Scalia's death. (The conference is when the court grants cert — accepts new cases.) If the conference goes ahead as scheduled, this will be the first time to gauge the effect of Scalia's death on that process.

What happens to those emergency requests that the Supreme Court gets?

Stay applications are requests that ask the Supreme Court to stop government action or put lower court rulings on hold until further decisions can be made in ongoing litigation, either at the high court or before a lower court.

Scalia's absence, quite simply, will make it impossible for the conservatives on the court to issue a stay without support from Justice Anthony Kennedy and at least one of the liberal justices. As has been noted often since Scalia's death, the Feb. 9 order granting a stay of — effectively and temporarily halting — Obama's Clean Power Plan during ongoing litigation would not have happened had it come to the justices at their next conference.

Additionally, applications out of the 5th Circuit — Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas — that previously went first to Scalia will now, under the court's rules, go to Kennedy for the time being. Most potentially close questions like this are generally referred by the justice receiving the application (called, "circuit justices") to the full court. But temporary orders often come from the individual justice and, technically, the circuit justice does have the capacity to issue a solo decision on the application (although the requesting party can then resubmit the application to another justice).

That sounds complex, but here's an example: The Supreme Court often gets last-minute request to put executions on hold. A "circuit justice" (i.e., Kennedy, overseeing applications out of Texas for now) could issue a temporary hold to allow the court more time to consider such a request.

The President and Senate:

What's all this talk about whether President Obama should nominate a new justice or whether the Senate will vote to confirm the nominee?

Because it's an election year, it always was unlikely that the Republican-controlled Senate would confirm many of President Obama's nominees.

Obama has said outright that he will be nominating a successor to Scalia — and that he expects the Senate to consider that nominee. Majority Leader Mitch McConnell and a number of high-ranking or key Republican senators have said that they will not vote to confirm a nominee until a new president is elected.

From Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley, who would oversee nomination hearings, to several of the Republicans up for re-election in 2016 who the White House would most likely try to get to oppose a filibuster of a nominee, many of the senators who would be integral to getting a vote for Obama's eventual nominee already have backed McConnell's position that no new justice should be confirmed until there's a new president.

When will Obama nominate someone to replace Scalia?

White House officials have said the will not nominate any successor to Scalia until the Senate returns. The Senate returns to Washington on Feb. 22.

Could Obama make a recess appointment?

The White House already put to rest talk that Obama should consider making a recess appointment of a justice — at least for now — a move that some on the left started urging once Republicans began their preemptive fight against any nominee.

The recess appointment power in the Constitution is as follows: "The President shall have Power to fill up all Vacancies that may happen during the Recess of the Senate, by granting Commissions which shall expire at the End of their next Session."

A key Supreme Court ruling in 2014 limited the power, holding that "a recess of more than 3 days but less than 10 days is presumptively too short to fall within the Clause."

The current recess, ending on Feb. 22, is for 10 days.

It appears, however, that the administration does not want to test the court, or the nation, with a temporary appointment to the high court under circumstances that fall right at the minimum possible recess length that the court had said was not a presumptively invalid recess length for purposes of the clause.

So … what happens now?

The only other real option — for the White House and for the Senate leadership, and for interest groups and politicians running for office — is politics.

Lots and lots of politics, on all sides and in every way. That's why everyone is saying something different about what past stats mean about Supreme Court justices being nominated or confirmed in presidential election years. Yes, more than a dozen Supreme Court nominees have been confirmed by the Senate in presidential election years (the most recent of which was 1988). On the other side of the coin, however, fewer than half of those Supreme Court seats became vacant during the presidential election year (the most recent of which was in 1932).

Outside of the recess appointment power, in other words, Obama's only options are appealing to the Senate — or appealing to the American people.

The Nominee:

Who will Obama nominate?

No one knows yet.

Are there any names that people think are more likely?

The early money for Obama's next Supreme Court nominee was clearly on U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit Judge Sri Srinivasan. Srinivasan had served in the Obama administration as a top appellate lawyer before being approved by the Senate in 2013 on a 97-0 vote for the powerful appeals court. That's the same court Scalia sat on before his nomination to the Supreme Court.

Next in line, under more ordinary circumstances, likely would have been Judge Patricia Millett, another Obama appointee to the D.C. Circuit.

If the nomination boils down to the politics of Republicans unwilling to consider Obama's nominee, however, a more unexpected nominee could be coming forward from the White House.

Some have posited that putting forth a senator — most often named are Sens. Amy Klobuchar (also named as possible pick during past vacancies) and Cory Booker — would be a way to put pressure on the Senate to act, but it's not clear that there is any real evidence to back up that theory.

SCOTUSblog's Goldstein wrote in two posts, faced with the Republican response to Scalia's death, that Democrats potentially would benefit more electorally by nominating a black or Latino person for the high court.

If that's the aim, California Attorney General Kamala Harris would fit the bill perfectly, Goldstein notes. However, given that she's running for the U.S. Senate now — and is already talked up as a possible future Democratic presidential nominee — it seems unlikely that she would want to take a Supreme Court path, at least right now. As such, Goldstein initially put his marker down on 9th Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Paul Watford, but later switched his prediction to Attorney General Loretta Lynch. California Supreme Court Justice Leondra Kruger also gets a mention from Goldstein, although he also notes that her age, 39, likely would make her too young to be a realistic nominee. (Politico's Josh Gerstein included Srinivasan, Millett, Watford, and Lynch on his list as well.)

The New York Times' Charlie Savage highlighted another potential nominee that would fit that bill: 11th Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Adalberto Jordan.

Judge Merrick Garland, also of the D.C. Circuit, also was named by Savage and Gerstein — the rare white male nominee mentioned by anyone as a possible nomination for a president who has made remaking the federal judiciary to be a far more diverse one a key, if often under-noticed, goal of his presidency. The final name put forth by Savage was 8th Circuit Judge Jane Kelly, a white woman.

Slate's Dahlia Lithwick puts forth several other names, including — in what would be one of the most clear signs that the administration expects no confirmation. They included: California Supreme Court Justice Goodwin Liu (previously denied a vote in the Senate on Obama's nomination of him to the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals). Lithwick also names 1st Circuit Court of Appeals Judge David Barron (one of the only other white men named as a possible pick); 9th Circuit Judge Jacqueline Nguyen; and a fourth potential D.C. Circuit nominee, Judge Robert L. Wilkins.

Unexplored in most of the discussions, however, is the fact that the person nominated is going to have to agree to undergo not only the extensive scrutiny any nominee for the high court would normally face — but also to agree to become a political football in the middle of two contested presidential primaries. Finally, they would have to be willing to do all of this while also accepting that there is no clear path to confirmation.

As such — and despite ideas discussed about expanding the types of people put on the Supreme Court — it would seem that the people most likely to allow their name to be put forward for nomination are going to come from the ranks of senior officials in the Obama administration who know their jobs likely are in their final year or from federal judges who already have lifetime tenure.

As with the presidential race and the Supreme Court vacancy itself, though, making predictions about this year is not the most fruitful of activities.