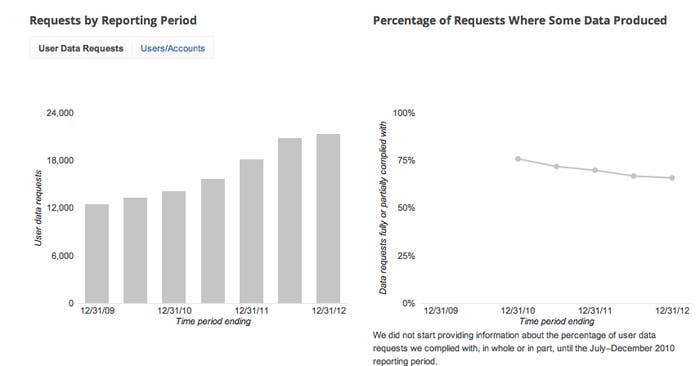

According to Google's Transparency Report, the company received 14,201 government requests for user data in 2010 and complied with 76% of them. In 2012, Google complied with only 66%, but due to the growing number (21,389 in 2012) of requests, Google actually forfeited user data thousands more times.

Google, and other tech giants, have been fighting back, but the trend is clear: Every year, more data is flowing from tech companies to the government.

During this same period, Google conceived of and announced its next big product: Google Glass, a wearable, connected device with a camera.

Now, imagine for a moment that wearable computing finally has its breakthrough moment. That a cheap version of Google Glass, after it becomes available to the masses, turns millions of users into full-time documentarians — of any and all things.

Then, imagine the FBI has access to that information.

Public reception of Glass has been mixed. The vast majority of people haven't tried it, or anything like it, but the concept is new and discomforting. For many, concerns center around Glass' inconspicuous ability to outwardly surveil the unsuspecting. With Glass there is no "point and shoot" — there's just "shoot."

Two decades ago, the FBI lobbied aggressively for Congress to pass the Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act (CALEA), mandating that all telephone switches be "wiretap friendly" in the event that the FBI needed to listen in on phone lines. In 2004, CALEA was extended to some broadband providers, like colleges, but larger web companies were not included.

CALEA set the stage for what's known as the FBI backdoor, the idea that the government — with legal authorization — can monitor communications through connected devices, often times without the user's knowledge.

Last year, one federal judge estimated there are probably around to 30,000 secret electronic surveillance orders issued by federal courts every year. Similarly, Wired reported the FBI was lobbying big tech companies like Yahoo, Facebook, and Google to request cooperation with backdoors for surveillance.

As with most surveillance, it's hard to know just how easy it is to gain access to user information. In 2012, Ars Technica found that it is highly unlikely that Apple could surrender encrypted data on an iPhone to authorities but noted that information in the cloud was much easier to obtain. (Since then, Apple, like Google, has actively encouraged users to migrate their iPhone's contents to the cloud.)

What makes Google Glass different — or at least seem different compared to smartphones — is intimacy. Wiretapping Glass doesn't just allow the government in your life, it allows it inside your head.

Kurt Opsahi at the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) says, "Google Glass, in essence, is not a difference of type, it's a difference of utility," he notes. "The issues in terms of privacy are similar to when video capabilities were introduced on cell phones. It caused a lot of consternation and worry, but the funtionality of glass is pretty much like that of a smartphone. It can record sounds, videos, and look up webpages in a similar way," he told BuzzFeed.

The real difference, Opashi suggests, is on the users' side.

"Where it could get interesting is if Glass becomes ubiquitous and you forget that it's out there on everyone's head. A situation where people are routinely recording and where constant documentation becomes a typical behavior is where it could get difficult. But right now it's a technology that's only available to a few thousand people."

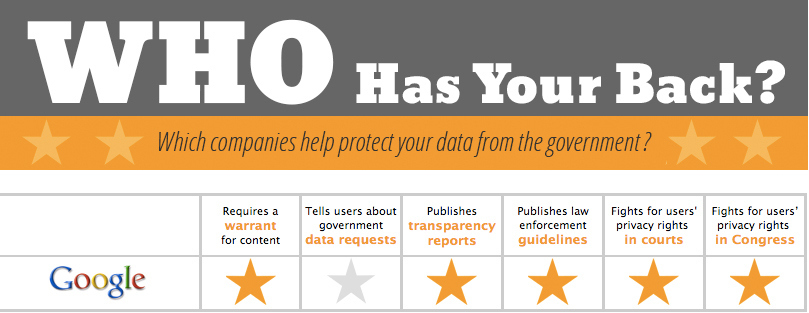

For Google, Glass makes the company's fight to maintain control of its data that much more important. An EFF privacy study conducted last week awarded Google five out of six stars in its fight to protect user data from the government. "On the whole, Google has been pushing back on goverment requests. While there are other privacy-related issues with Google and the incredible amounts of information it has about its users, in terms of the company's willingness to protect users from the government, they have and continue to be good about that."

In April, Google also made news as the first major communications company to push back against government national security probes to obtain user information, earning Google high praise from privacy organizations.

"Privacy and respecting the security of our users are is central to our mission at Google," a company spokesperson told BuzzFeed. "When we get a government request we make sure it follows the law as well as Google's policies before complying. We will also, in many cases, work to notify users unless prohibited by law or court order and if we believe a request is overly broad we will seek to narrow it."

Despite Google's efforts, the safety of user data could be out of its hands. FBI documents obtained by the ACLU on Wednesday suggest the agency may be reading electronic communications without a warrant, which, if true, would not only violate the Fourth Amendment, but add a troubling new dimension to electronic privacy — and the devices in our pockets, or on our heads.