The internet is not a place of fierce loyalty. Create a transformational product or build a better service and people will use it. Thus Hotmail gave way to Gmail, and MySpace to Facebook. So you can understand why Google thought it could build a better social network in Google+. But that’s not what happened. Or at least, it wasn’t able to build a more popular social network. But why not?

The answer to the question of why Google+ failed is simple. It’s the reason why any social network succeeds or fails. The answer is photos. Google+ now has one of the best photo management tools there is, period. It finds your best pictures for you, it’s amazingly searchable, it auto-generates highlight films and cool photos albums, and it even turns your burst shots into animated GIFs. Fancy! But all of that came far too late in its history. The big mistake Google+ made was in starting out as a place for people to have meaty in-depth discussions.

It’s easy to see how Google+ came at this from the wrong direction. Google+ promised better organization and the ability to build more meaningful communities. It was about optimizing the connections that you’ve already made through a cumbersome sorting process. Rather than allowing people to subconsciously construct communities through the sharing of their lives — be it a 10,000-foot survey of one’s life, a daily check-in, or a constant, real-time update — Google+ sought to build a community through the laborious task of...well, building a community.

Google is powerful, rich as hell, and full of smart engineers and theorists who understand the internet better than most. That’s why Google+, in whatever form, isn’t abandoned yet. But as history has shown, for a social network to succeed it has to feel exceedingly human. It has to be a place that people go to feel something — to laugh or cry or to become frustrated or amused. Photos capture that humanity and reflect it back on people in a thousand different, unexpected ways. Bradley Horowitz, the same guy who bought the internet’s first hit photo sharing site, Flickr, for Yahoo back in the day, now heads Google+, and made some news recently about beefing up its photos product. This is decidedly good news, both for Google photos and for the social network on life support. Can Google transform Google+ into a window into its users' lives? That's unclear, but photos are the best chance its got.

Let me explain. For much of the internet’s recent history, the dominant unit of social technology has been instant messaging. Today, as was the case in the 1990s, instant messaging dictates who has power in the tech world. It proved to be crucial for AOL and later Yahoo, followed by Google, and Facebook, and then moving into texting apps like WhatsApp, Kik, and Viber. Each of these instant-messaging clients, going back to AIM, is and was its own social network — they kept people coming back because that’s where their friends and family and co-workers happened to be. Consider the $18 billion Facebook paid for WhatsApp: Messaging is valuable.

But photos may be even more valuable. While Facebook was a cultural phenomenon well before it introduced photo sharing in October 2005, its position as a transformative global social force was still precarious before the site began allowing users to upload, organize, and share large photo albums. Facebook quickly became the destination for digital camera photo dumps. And as its users graduated and grew up, they kept uploading, the pictures slowly evolving with them, from party snapshot to wedding photos to baby pictures. When Facebook opened its account requirement gates wide, moms, dads, aunts, uncles, and even grandparents joined in because that’s where their friends and family and co-workers happened to be. And they brought their photos with them.

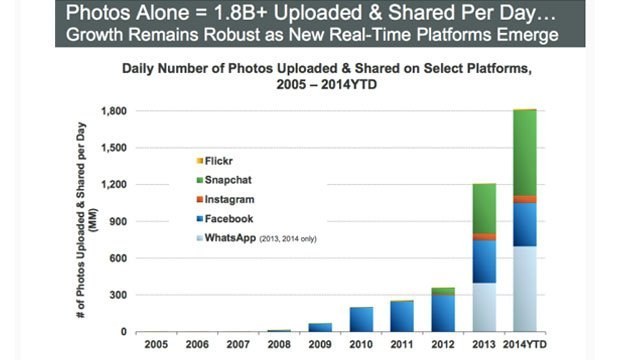

Add to this Facebook’s News Feed, with its algorithmically driven ability to surface these photos, and you’ve taken a cultural phenomenon and turned it into a world-changing, generation-shaping colossus. In 2013, Facebook announced that users were uploading 350 million photos each day.

And then photos and instant messaging — the web’s two unassailable kingmakers — began to merge as smartphones became ubiquitous. The evolution of the camera phone from a novelty feature to a device that quite literally obliterated the need to have a traditional camera resulted in a flood of images onto the web. In 2014, nearly 1.8 billion photos were uploaded per day to the internet. Perhaps calling it a flood doesn’t do it justice. It’s a full-scale breach of the seawalls.

Instagram was the first to harness this mobile photography phenomenon in a meaningful way. Blogger and investor Om Malik wrote in a recent piece about digital photography that “the ultimate beauty of iPhone” is that “it has made photography not scary. It has removed technology and made it just an act of creation.” Better than anyone else, Instagram seized upon this and turned its camera tool into a home screen sanctuary that allowed professionals and amateurs alike to quickly enhance and transform their photos.

In Instagram’s case, thanks to the mobile nature of the photos, these communities felt even more intimate than Facebook’s more static albums. Following someone on Instagram wasn’t just a peek into their lives — it was a look at their day as it unfolded. Facebook, all too familiar of the importance of the currency of photo communities, smartly snatched it up for a steal in 2012.

Instagram’s intimate communities, led by its youngest users, began to use the service in unexpected ways, turning photo comments into message boards. Photos were not simply static images, but moments around which to gather and converse.

But if Instagram’s near-real-time photo-commenting use revealed itself as a strange hybrid of instant messaging and photos, Snapchat’s introduction and steep rise fully blurred all distinctions between the internet’s two most powerful social currencies.

While smartphone users had begun to grow familiar with sending more images via SMS and over-the-top texting apps like WhatsApp, Kik, Line, and iMessage, Snapchat combined the images and text, flipping the traditional unit of instant messaging on its head. While Snapchat’s distinguishing feature is ephemerality, its disappearing messages only served to enhance its truly genius and most insidious feature: an effortless multimedia instant message.

If Facebook allows a peek into a person’s life, often at a bit of a distance, and Instagram is a peek into a person’s day as it unfolds, Snapchat is a look at a person’s day in real time. This idea was made more explicit when Snapchat introduced its Stories feature, which allows users to stitch together snaps for a larger portrait of a day or event. Messages disappear so there’s less posturing and art involved. You snap the same way you text: quickly, informally, and at high volumes. And since snaps can be sent out to multiple users, but not as group chats, one message can generate dozens of conversations. The communities may be siloed but the shared experience and community is delivered with ruthless efficiency.

And it shows. As of last May, Snapchat users were sending 700 million photos and videos each day. In August the company reported having 100 million monthly active users, but in December TechCrunch speculated the app was closing in on 200 million monthly actives. For some younger groups, it’s replaced or severely altered texting.

Social networks should be windows, not ballrooms or hallways.

Taken together, this history serves as evidence for a larger point about social networks, but especially modern ones: At their core, they must be windows into people’s lives.

Put another way, just providing a forum for discussion often isn’t enough to provide utility and assure the longevity of an online community.

Put another way: Nobody wants to hear your opinion, man. Nobody really cares what you think. Pics or GTFO.