If you want to understand Ezra Klein's departure from the Washington Post to Vox Media, as well as the context of the larger conversation about "the future of web journalism," this line from a recent interview is a good place to start:

I was intent on only partnering with somebody who could make the product better than I ever could. Otherwise we should just go the startup route... I trust them more than I trust myself or any of my team to build awesome tech and design teams and exquisite platforms. They really make us better on those dimensions from the beginning. We're building this from scratch and this will be a substantial effort and take many months but they've been thinking about it already they're making us smarter.

One way to interpret this statement is as a mere courtesy: Klein's proposal to the Post was made because he respects and admires the publication that helped make his name. Historically, the Post's relationship with the web has been a tumultuous one — until mid-2009, the company refused to house its print and digital staffers under the same roof, or even in the same state. Digital staffers worked in a separate building in Alexandria, Va.

Last year, Kara Swisher detailed the Post's disappointing relationship with the web in an open letter to Jeff Bezos:

Like a lot of newspapers, the Post soon got to the Web, too, but with offerings that were not as compelling as those being created by native Internet companies, and with a series of ever-changing business plans that only served to confuse readers. While it is easy to see the problems now, the truth is, it was also easy to see them then.

This is all to illustrate that the Post has never had deep roots in technology. It has tried, and had success with, various internet ventures — WaPo labs, an R&D style digital company inside the paper has hosted some forward thinkers in the field of media and technology — and has a large website. But all these are organs of the bigger thing, offshoots or subordinates of the media mothership.

So it makes sense that Katharine Weymouth would pass on Klein's venture, and explains why Jeff Bezos didn't even bother to reply to Klein's pitch, as a recent Washingtonian Magazine article revealed. Klein's new venture wasn't just about a starting a property outside the walls of the Post's brand; it was about finding new ways to present journalism for the web, which, translated into practical terms, means funding a tech startup. Those 30 requested staffers likely weren't just editorial, but product and sales staffers as well. People who could come in and build a new style of news product, who would bring a vision of their own to complement and sometimes overrule, at least on tech matters, whatever Klein has come up with already. It probably sounded like a startup pitch from a guy who's still looking for his other co-founder. It kind of was!

Most of the "future of media" columns this week, written largely by established, authoritative critics at legacy media properties, lacked crucial context. This is a crowd that deeply understands the players in and economics of the media business, but that privileges old media over new (or even just old-new over new-new). Today's most prominent media reporters watched and chronicled print's financial troubles and the rise of scrappy web ventures, and drew from their own experiences with both, documenting and living in an industry changing against its own will. It was a short, under-appreciated golden era of media reporting — immensely compelling writers finding themselves at the center of a fascinating and consuming story.

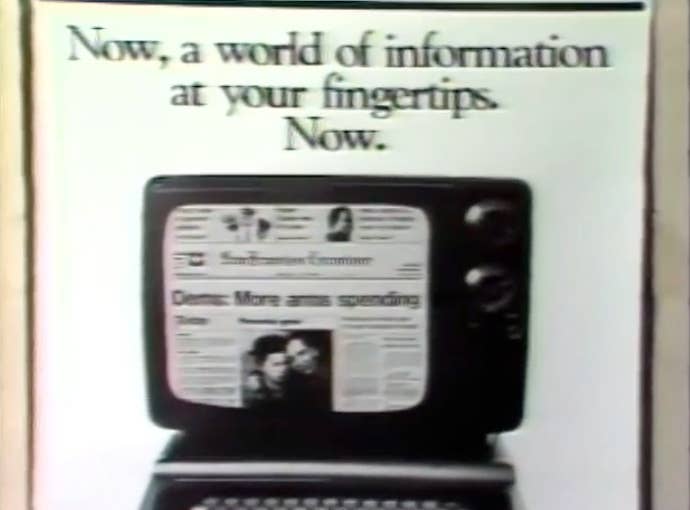

But media reporting today is, for better or for worse, inextricable from technology reporting. Tech — the internet, CMSes, distribution and production — is not just a factor for media companies, but an overwhelming context.

Here, for example, is George Packer writing for the New Yorker, addressing the technological component of Klein's new venture:

According to [David] Carr, "Everything at Vox, from the way it covers its subjects, the journalists it hires and the content management systems on which it produces news, is optimized for the current age." This, too, is opaque in a way that's pretty much endemic whenever journalists write about anything having to do with technology, as if they've become captive to the assured, technical-sounding, empty language of their beat—as if they need to use its language in order to be taken seriously in that world, and to hell with the old-fashioned, outdated virtue of clarity. Surrendering to jargon is a sign of journalism's dismal lack of self-confidence in the optimized age of content-management systems.

Tech is cursed with terrible jargon, and people who write about tech are vulnerable to their own fatal blindnesses. But Packer dismisses the subject of technology as a smokescreen intended to keep people from discussing what the Project X will really look like, rather than what it really is: the difference between a successful new media venture and a flop.

Klein's attraction to Vox, in addition to the company's financial resources, comes down to tech. Vox's head of product, Trei Brundrett, summed it up nicely in a recent tweet:

It's not the technology itself. It's about having a technology culture. That's our moat y'all. & we been digging it for 6+ years.

Reuters' media columnist Jack Shafer did his best to pour some cold water on the importance of new media tech, noting that low cost of entry, lack of contracts, and the fast pace of innovation make for an untenable degree of uncertainty at any web journalism venture in the "long run":

The velocity of the Web rewards the swift and those with new ideas. But in the long term, neither Klein's remarkable talents nor Vox's remarkable technology will be sufficient to build a sustaining moat for their partnership. Not to disparage Klein and Vox, but anything they can do can probably be done cheaper and maybe even better by somebody else. Any success they have in their niches will quickly be imitated. Any stars they "create," as Gawker did with Zimmerman, will be recruited by other startups or employers. Vox better be prepared for a long, hard slog.

Shafer's criticisms raise the question of just how "long" his "long run" view really is. Vox has been building a technology platform for almost seven years (back when the Post's digital team worked in a different office). Gawker, another of Shafer's examples, is a teenager. That's 13 years of culture, and of thinking critically and exclusively about the internet. That's multiple native platforms developed, refined, and replaced entirely. (BuzzFeed's CMS has changed substantively nearly every week since I started working here.)

What this really means is easier to understand if you've experienced it firsthand. It's the difference between a CMS where you're vaguely familiar with the capabilities, where feature requests are submitted but rarely discussed, and where the way the platform works isn't really your business, vs. a system that doesn't just respond to your requests but preempts them, then moves on to something more interesting. In print terms, a dynamic proprietary platform is like having an exceptional art department at a magazine: You come with a roughly formed idea in your head, bumble through the pitch, and get back something that's not exactly what you asked for — or maybe not what you asked for at all — but that's much, much better.

Pretty much everyone I know in journalism writes in the CMS. I do not, haven't throughout my career. I wonder if this makes me worse.

The columnists are right about one thing: the uncertainty. There are the rising and falling CPMs, and the increasingly meaningless metrics like pageviews; the fickle distribution from social platforms like Facebook, which are subject to business model-ruining algorithm tweaks; the appearance and disappearance of new content and packaging techniques — Listicles! Upworthy headlines! GIFs! — and the all-important editorial vision of a media properties' leaders, be they explanation-obsessed "wunderkinds" or scoop-driven hard news types. Nobody has perfected the "new media model" — there were plenty of old media models, and we should expect a wide variety now too.

But the best of these models — these publications — will only emerge from environments that privilege tech. Is that a smokescreen? Maybe. But there's something real on the other side.