Ryan Shapiro is arguably the king of prison email. Since 2001, when Shapiro founded JPay as a more efficient and transparent way to wire money to inmates, his organization has quietly grown into one of the largest private corrections technology companies in the country. Roughly 2 million inmates have access to JPay’s platform, which now includes prison email, a digital music subscription service, MP3 players, Android tablets, and remote video visitation systems. Soon they’ll have access to a new educational service as well.

On Wednesday, JPay formally announced its Lantern tablet education program with Ashland University in six state prisons across Ohio. Since last July, JPay and Ashland have been piloting the program, enrolling 442 inmates over two semesters in Chillicothe, Grafton, Richland, Lake Erie, Mansfield Reformatory, and Cuyahoga County prisons.

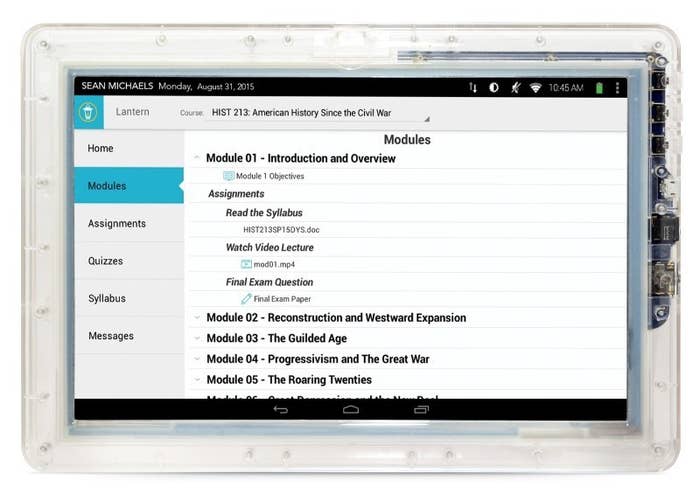

It works like this: Inmates who enroll in the education program are issued JPay's 10-inch secure JP5 tablets by the university (the tablets can also be purchased by inmates' families through JPay). These rudimentary Android tablets cannot access the web, but they allow secure emailing (communication is filtered in both directions by prison security officials) and offer access to an iTunes-style music purchasing system, and Lantern -- a two-way education platform that allows inmates access to coursework, lesson plans, instructional videos, and learning apps, as well as a suite of Microsoft Office programs like Word and Excel. Lantern’s curriculum includes an array of college introductory courses in everything from management and entrepreneurship to financial literacy.

“About two years ago we realized, ‘OK, we have this massive network of kiosks throughout prison systems in the U.S. and we touch a majority of the inmates in the country,'” Shapiro told BuzzFeed News. “'So how do we make use of that reach to do something transformative?’ When tablets really started taking off, we knew that education was the place to go.” Shapiro likes to rattle off stats like this one from the Rand Corporation that suggests inmates who receive education in prison are 43% less likely to become repeat offenders. And it’s this principle — that education reduces recidivism and thus the overall prison population — that led JPay to partner with Ashland University’s director of business and economic education, John Dowdell.

Dowdell has been involved in correctional education for 32 years and sees in JPay the potential to drastically reform education inside prisons. “When I consider what a university should be — and I see them as instruments of change in society — I feel we need to be involved in correctional education and make it truly a mission-driven endeavor,” Dowdell told BuzzFeed News. “There's probably no greater population we could serve with new education technology than prisons.”

Currently, Lantern students have been issued 1,284 college credits in two semesters using JPay tablets, a sign that the program can work, provided state prisons cooperate and JPay’s infrastructure can work at scale. “Education is not the hard sell. Getting the tablet networks and kiosks in there over the years, now that was hard,” Shapiro said. “Now it’s a matter of how do we get all these different states and counties, and match them with colleges and universities and get them on board.”

JPay currently has tablets in tens of thousands of inmates’ hands and contracts with most state and county prisons (the company doesn't operate inside federal prisons). Shapiro argues that the company’s platform reaches about two-thirds of all those incarcerated in the country, meaning Lantern has the potential for wide adoption in the future -- assuming a wide deployment. If JPay can scale the project, it could dramatically increase the number of inmates with access to some form of higher education.

It's too early to gauge the depth and breadth of Lantern’s impact , but Dowdell, who personally teaches roughly 20 inmates, sees it and technology like it as vital to the long-term success of rehabilitating prisoners.

“You're basically freeze-drying an inmate in prison when it comes to their awareness of modern technology,” Dowdell said. “If I’m jailed in 2004 and come out in 2016 with the same tech toolbox, I’m basically technologically illiterate, which means now I’m more behind trying to get a job and to transform to be a productive member in society.”

The State of Ohio Correctional System declined to make available any inmates for this story, but Shapiro and Dowdell cited multiple instances where inmates who'd never seen a smartphone, laptop, or tablet mastered Microsoft Office and Excel in weeks. “More than anything else, they've got so much time to learn this stuff,” Shapiro said. “And these are skills that give them a shot at securing better jobs upon release. Better jobs can often mean less of a chance that people come back.”

On the inside, Dowdell says the introduction of the tablets has had some surprising side effects, namely bridging generational gaps between inmates. “There's a hierarchy in prisons and it's often … older inmates dictating terms to the younger ones. But now these 18- and 19-year-old kids, they know how to use the tools and they're teaching those who might be technologically illiterate. It's changing the relationship.”

Promising news, but changing the broader correctional system in a meaningful way and at scale will likely be a challenge. Outdated prison infrastructure is difficult to fix; JPay is working to install wireless internet connections in state prisons across the country. And repairing broken devices and communicating product updates and bug fixes to users can be challenging. “We’re kind of the first people to ever offer customer service to inmates, and it turns out it's not an easy thing,” Shapiro said.

But Shapiro is undaunted. JPay doesn't make money from Lantern beyond the sale of its tablets, and he’s quick to point out that the company is more of an attempt to improve the correctional system than it is a cash cow. Asked if he’s ever faced criticism for supplying lawbreakers with tablets and video conferencing tech, he offers a curt reply. “Only from online comments sections do I ever hear anything about this being an extravagance for inmates. I’ve yet to hear any law enforcement official say, ‘This is something inmates don’t deserve.' Most of the time they want to make an inmate’s life better so that their lives are better.”