A new study from the University of Pennsylvania's Annenberg School claims that Wikipedia might hold the key to understanding how Iran censors, and controls, the internet. The answer, in four words: with a heavy hand.

Reports of internet censorship in Iran have been a constant in the international media, but until now little was known about the specific systems and methods the country uses to restrict the flow of information online.

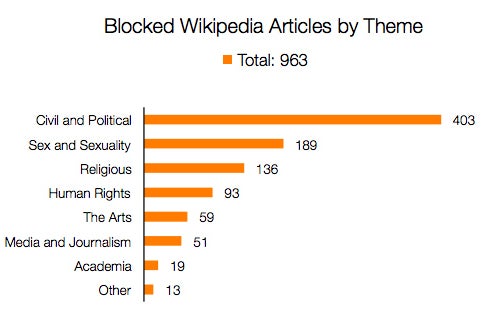

The study, which used proxy servers in Iran to scan Wikipedia's Persian-language articles, found that out of 800,000 entries, the Iranian government blocked 1,187 Persian Wikipedia URLs that corresponded to 963 unique article pages, including 15 of the site's top-100 Persian language articles. Of the top articles blocked, many contained "entries about homosexuality, orgasms, former Iranian President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, and activist rapper Shahin Najafi," the study said.

According to Collin Anderson, the researcher in charge of the study, the growing popularity of Wikipedia's Persian-language site (new entries have grown tenfold since 2006) created a microcosm from which to study the Iranian internet as a whole. "It's useful place to uncover the types of online content forbidden and an excellent template to identify keyword blocking themes and filtering rules that apply across the greater internet," he told BuzzFeed.

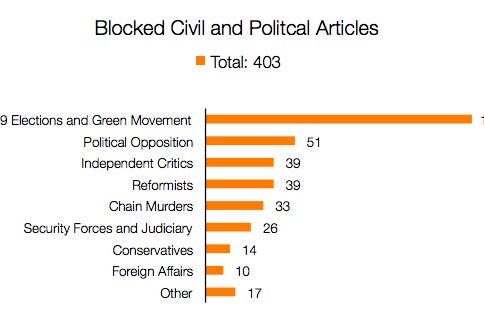

Of the 1,187 blocked articles, the vast majority are designed to restrict access to articles chronicling Iran's history of human rights abuses or that contain biographical information on government authorities.

Government censors filtered 93 articles concerning human rights; nearly 42% of the blocked government entries — 308 in all — were bio pages of activists, politicians, government critics, and protesters. Most, if not all, entries surrounding the disputed 2009 elections and uprisings were also inaccessible through Iranian proxy servers.

"Most censorship appears to be focused on hiding a data trail," Anderson said. "For example, if you look for a set of serial killings against intellectual establishment in late 1990s, all the victims' pages were blocked, creating something of a double victimization, where critics of the government were not only eliminated but their histories removed as well."

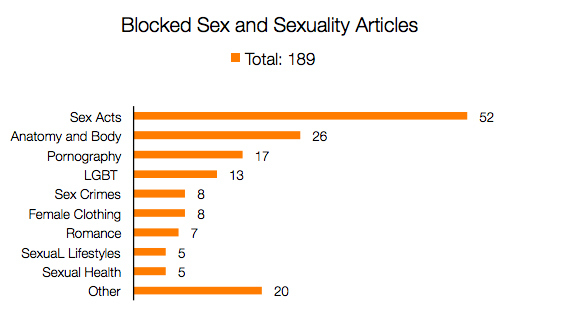

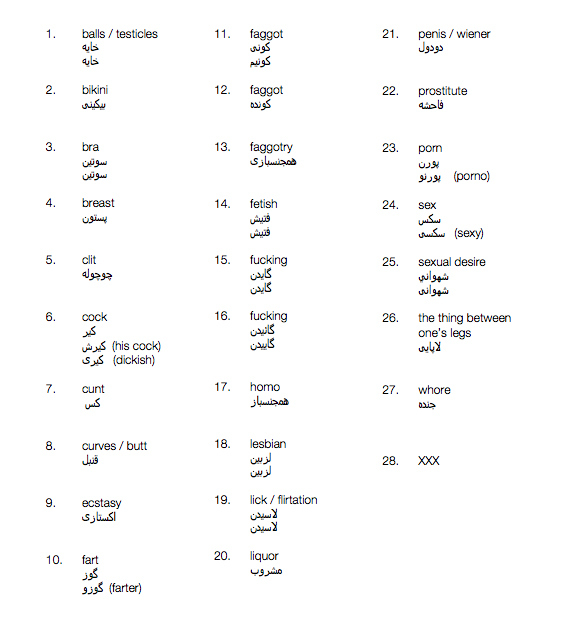

Articles deemed to be about sex or of a sexual nature are often popular, and a main target of keyword filtering. Of the 202 keyword-filtered URLs, 179 contained "sex and sexuality." Entries with words including "pimp," "dick," "breasts," "fag," "fart," and "liquor" were all banned. Even more troubling, the study found 31 of Iran's manually censored articles contained information on sexual health, bodily functions, and basic anatomy.

The majority of filtered religious articles target the Baha'i faith — Iran's largest non-Muslim minority religion — and according to the study, "fifty-nine blocked entries discussed tenets of the Baha'i faith or important Baha'i individuals and institutions, such as entries about Baha'i prayers, the Baha'i holy book Hidden Words, or the faith's governing institution, the Universal House of Justice."

Some of the censored Wikipedia keywords:

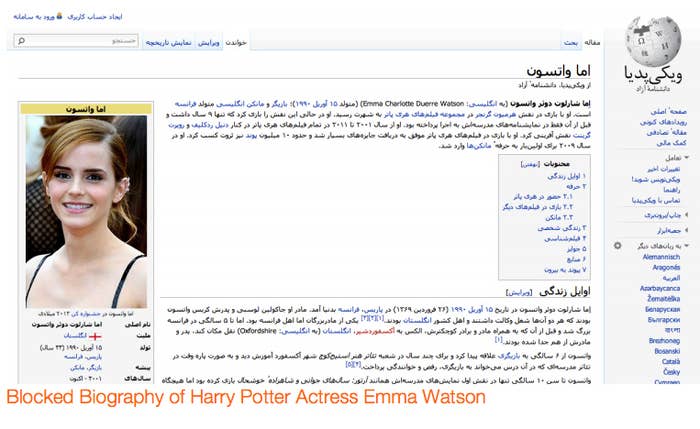

While the most conspicuously censored articles in the study are of a political, religious, or sexual nature, keyword targeting and censorship affects a wider range of content. Anderson found that while a number of Iranian art and culture entries were blocked, so were seemingly random entries for Western actresses and celebrities like Kristen Stewart and Emma Watson.

For Iran, the study comes at a pivotal moment for internet freedom. Iran's new president, Hassan Rouhani, has stated publicly his belief in the right for all Iranians to access information online, as long as it falls within legal and cultural limits. "The information we're uncovering shows that this censorship runs deep throughout the country," Anderson said, adding that he hopes increased monitoring from studies like this one will put pressure on the regime to change.

"I think there will always be a part of the Iranian security state that believes the internet is enemy," Anderson said of possible reform. "The 2009 revolutions gave them lots of reason to feel that way. But I believe a lot of these pages we are surfacing will eventually get unblocked, and I think we may see a day in next six months to a year where Facebook or Twitter will be unblocked."

"Iran is not North Korea. It's still technically an internally deliberative state with elections and public pressure," he said. "If we continue to call attention to and understand how censorship works, I think things will get better even if it is pretty bleak right now."