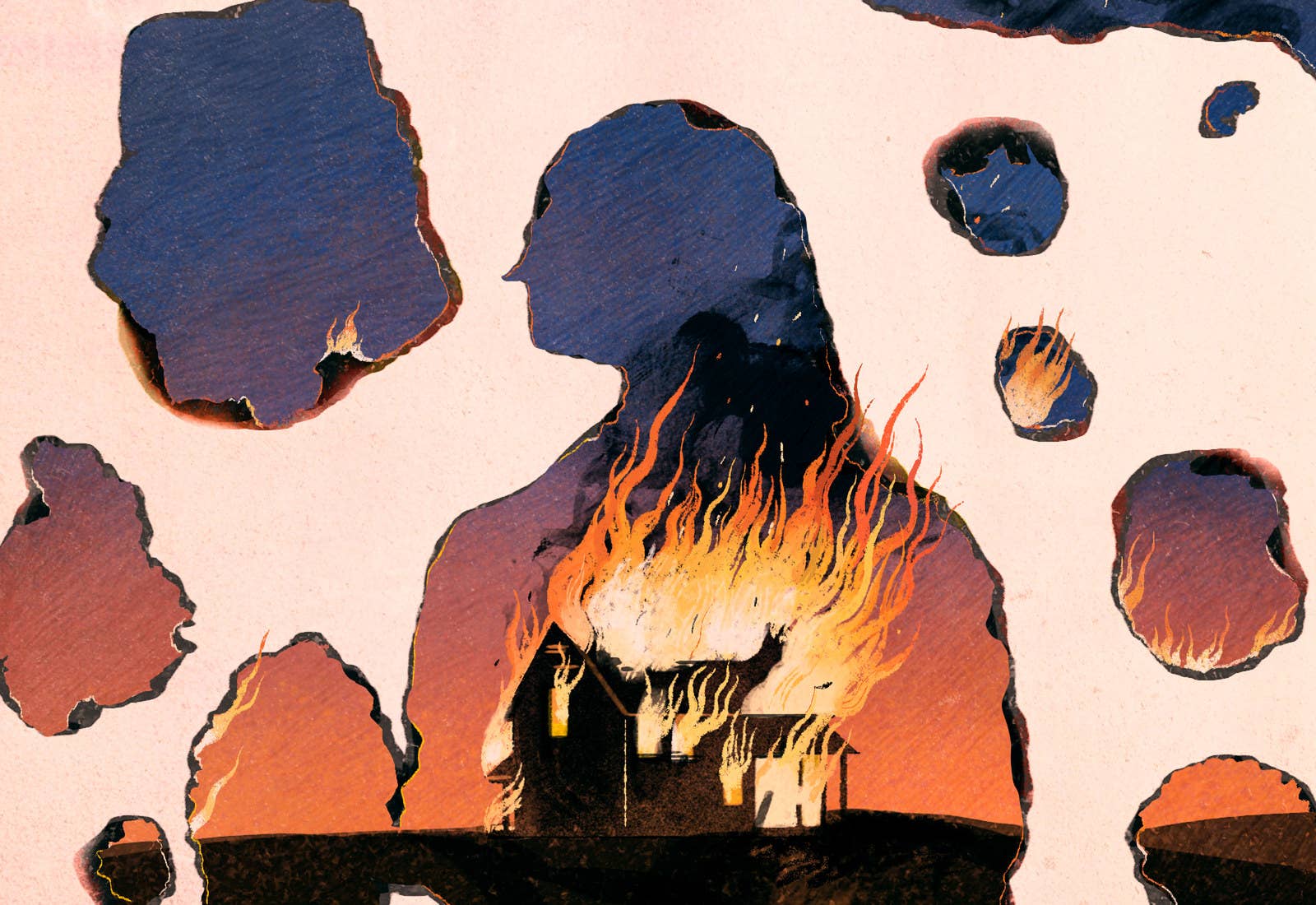

Everyone in Shaker Heights was talking about it that summer: how Isabelle, the last of the Richardson children, had finally gone around the bend and burned the house down. All spring the gossip had been about little Mirabelle McCullough—or, depending which side you were on, May Ling Chow—and now, at last, there was something new and sensational to discuss. A little after noon on that Saturday morning in May, the shoppers pushing their grocery carts in Heinen’s heard the fire engines wail to life and careen away, toward the duck pond. By a quarter after twelve there were four of them parked in a haphazard red line along Parkland Drive, where all six bedrooms of the Richardson house were ablaze, and everyone within a half mile could see the smoke rising over the trees like a dense black thundercloud. Later people would say that the signs had been there all along: that Izzy was a little lunatic, that there had always been something off about the Richardson family, that as soon as they heard the sirens that morning they knew something terrible had happened. By then, of course, Izzy would be long gone, leaving no one to defend her, and people could — and did — say whatever they liked. At the moment the fire trucks arrived, though, and for quite a while afterward, no one knew what was happening. Neighbors clustered as close to the makeshift barrier — a police cruiser, parked crosswise a few hundred yards away — as they could and watched the firemen unreel their hoses with the grim faces of men who recognized a hopeless cause. Across the street, the geese at the pond ducked their heads underwater for weeds, wholly unruffled by the commotion.

Mrs. Richardson stood on the tree lawn, clutching the neck of her pale-blue robe closed. Although it was already afternoon, she had still been asleep when the smoke detectors had sounded. She had gone to bed late, and had slept in on purpose, telling herself she deserved it after a rather difficult day. The night before, she had watched from an upstairs window as a car had finally pulled up in front of the house. The driveway was long and circular, a deep horseshoe arc bending from the curb to the front door and back—so the street was a good hundred feet away, too far for her to see clearly, and even in May, at eight o’clock it was almost dark, besides. But she had recognized the small tan Volkswagen of her tenant, Mia, its headlights shining. The passenger door opened and a slender figure emerged, leaving the door ajar: Mia’s teenage daughter, Pearl. The dome light lit the inside of the car like a shadow box, but the car was packed with bags nearly to the ceiling and Mrs. Richardson could only just make out the faint silhouette of Mia’s head, the messy topknot perched at the crown of her head. Pearl bent over the mailbox, and Mrs. Richardson imagined the faint squeak as the mailbox door opened, then shut. Then Pearl hopped back into the car and shut the door. The brake lights flared red, then winked out, and the car puttered off into the growing night. With a sense of relief, Mrs. Richardson had gone down to the mailbox and found a set of keys on a plain ring, with no note. She had planned to go over in the morning and check the rental house on Winslow Road, even though she already knew that they would be gone.

By then, of course, Izzy would be long gone, leaving no one to defend her, and people could — and did — say whatever they liked.

It was because of this that she had allowed herself to sleep in, and now it was half past twelve and she was standing on the tree lawn in her robe and a pair of her son Trip’s tennis shoes, watching their house burn to the ground. When she had awoken to the shrill scream of the smoke detector, she ran from room to room looking for him, for Lexie, for Moody. It struck her that she had not looked for Izzy, as if she had known already that Izzy was to blame. Every bedroom was empty except for the smell of gasoline and a small crackling fire set directly in the middle of each bed, as if a demented girl scout had been camping there. By the time she checked the living room, the family room, the rec room, and the kitchen, the smoke had begun to spread, and she ran outside at last to hear the sirens, alerted by their home security system, already approaching. Out in the driveway, she saw that Trip’s Jeep was gone, as was Lexie’s Explorer, and Moody’s bike, and, of course, her husband’s sedan. He usually went into the office to play catch-up on Saturday mornings. Someone would have to call him at work. She remembered then that Lexie, thank god, had stayed over at Serena Wong’s house last night. She wondered where Izzy had gotten to. She wondered where her sons were, and how she would find them to tell them what had happened.

The previous June, when Mia and Pearl had moved into the little rental house on Winslow Road, neither Mrs. Richardson nor Mr. Richardson had given them much thought. They knew there was no Mr. Warren, and that Mia was thirty-six, according to the Michigan driver’s license she had provided. They noticed that she wore no ring on her left hand, though she wore plenty of other rings: a big amethyst on her first finger, one made from a silver spoon handle on her pinky, and one on her thumb that to Mrs. Richardson looked suspiciously like a mood ring. But she seemed nice enough, and so did her daughter, Pearl, a quiet fifteen-year-old with a long dark braid. Mia paid the first and last month’s rent, and the deposit, in a stack of twenty-dollar bills, and the tan VW Rabbit—already battered, even then—puttered away down Parkland Drive, toward the south end of Shaker, where the houses were closer together and the yards smaller.

Mrs. Richardson looked at the house as a form of charity.

Winslow Road was one long line of duplexes, but standing on the curb you would not have known it. From the outside you saw only one front door, one front-door light, one mailbox, one house number. You might, perhaps, spot the two electrical meters, but those—per city ordinance—were concealed at the back of the house, along with the garage. Only if you came into the entryway would you see the two inner doors, one leading to the upstairs apartment, one to the downstairs, and their shared basement beneath. Every house on Winslow Road held two families, but outside appeared to hold only one. They had been designed that way on purpose. It allowed residents to avoid the stigma of living in a duplex house — of renting, instead of owning — and allowed the city planners to preserve the appearance of the street, as everyone knew neighborhoods with rentals were less desirable.

Shaker Heights was like that. There were rules, many rules, about what you could and could not do, as Mia and Pearl began to learn as they settled into their new home. They learned to write their new address: 18434 Winslow Road Up, those two little letters ensuring that their mail ended up in their apartment, and not with Mr. Yang downstairs. They learned that the little strip of grass between sidewalk and street was called a tree lawn — because of the young Norway maple, one per house, that graced it — and that garbage cans were not dragged there on Friday mornings but instead left at the rear of the house, to avoid the unsightly spectacle of trash cans cluttering the curb. Large motor scooters, each piloted by a man in an orange work suit, zipped down each driveway to collect the garbage in the privacy of the backyard, ferrying it to the larger truck idling out in the street, and for months Mia would remember their first Friday on Winslow Road,

the fright she’d had when the scooter, like a revved-up flame-colored golf cart, shot past the kitchen window with engine roaring. They got used to it eventually, just as they got used to the detached garage — stationed well at the back of the house, again to preserve the view of the street — and learned to carry an umbrella to keep them dry as they ran from car to house on rainy days. Later, when Mr. Yang went away for two weeks in July, to visit his mother in Hong Kong, they learned that an unmowed lawn would result in a polite but stern letter from the city, noting that their grass was over six inches tall and that if the situation was not rectified, the city would mow the grass — and charge

them a hundred dollars — in three days. There were many rules to be learned.

In Shaker Heights there was a plan for everything.

And there were many other rules that Mia and Pearl would not be aware of for a long time. In Shaker Heights there was a plan for everything. When the city had been laid out in 1912 — one of the first planned communities in the nation — schools had been situated so that all children could walk without crossing a major street; side streets fed into major boulevards, with strategically placed rapid-transit stops to ferry commuters into downtown Cleveland. In fact, the city’s motto was — literally, as Lexie would have said — “Most communities just happen; the best are planned”: the underlying philosophy being that everything could — and should — be planned out, and that by doing so you could avoid the unseemly, the unpleasant, and the disastrous.

But there were other, more welcoming things to discover in those first few weeks as well. For Pearl, there was the discovery of their landlords, and of the Richardson children.

Moody was the first of the Richardsons to venture to the little house on Winslow. He had heard his mother describing their new tenants to his father. “She’s some kind of artist,” Mrs. Richardson had said, and when Mr. Richardson asked what kind, she answered, jokingly, “A struggling one.”

“It’s all right,” she reassured her husband. “She gave me a deposit right up front.” “That doesn’t mean she’ll pay the rent,” Mr. Richardson said, but they both knew it wasn’t the rent that was important — only three hundred dollars a month for the upstairs — and they certainly didn’t need it to get by.

No, it wasn’t the money that mattered. The rent — all five hundred dollars of it in total — now went into the Richardsons’ vacation fund each month, and last year it had paid for their trip to Martha’s Vineyard, where Lexie had perfected her backstroke and Trip had bewitched all the local girls and Moody had sunburnt to a peeling crisp and Izzy, under great duress, had finally agreed to come down to the beach — fully clothed, in her Doc Martens, and glowering. But the truth was, there was plenty of money for a vacation even without it. Because they did not need the money from the house, it was the kind of tenant that mattered to Mrs. Richardson. She wanted to feel that she was doing good with it. Her parents had brought her up to do good; they had donated every year to the Humane Society and UNICEF and always attended local fund-raisers, once winning a three-foot-tall stuffed bear at the Rotary Club’s silent auction. Mrs. Richardson looked at the house as a form of charity. She kept the rent low — real estate in Cleveland was cheap, but apartments in good neighborhoods like Shaker could be pricey — and she rented only to people she felt were deserving but who had, for one reason or another, not quite gotten a fair shot in life. It pleased her to make up the difference.

Mr. Yang was the exact kind of tenant Mrs. Richardson wanted: a kind person to whom she could do a kind turn, and who would appreciate her kindness.

Mr. Yang had been the first tenant she’d taken after inheriting the house; he was an immigrant from Hong Kong who had come to the United States knowing no one and speaking only fragmentary, heavily accented English. Over the years his accent had diminished only marginally, and when they spoke, Mrs. Richardson was sometimes reduced to nodding and smiling. But Mr. Yang was a good man, she felt; he worked very hard, driving a school bus to Laurel Academy, a nearby private girls’ school, and working as a handyman. Plus, Mr. Yang kept the house in impeccable shape, repairing leaky faucets, patching the front concrete, and coaxing the stamp-sized backyard into a lush garden. Every summer he brought her Chinese melons he had grown, like a tithe, and although Mrs. Richardson had no idea what to do with them — they were jade green, wrinkled, and disconcertingly fuzzy — she appreciated his thoughtfulness anyway. Mr. Yang was the exact kind of tenant Mrs. Richardson wanted: a kind person to whom she could do a kind turn, and who would appreciate her kindness.

With the upstairs apartment she had been less successful. The upstairs had had a new tenant every year or so: a cellist who had just been hired to teach at the Institute of Music; a divorcée in her forties; a young newlywed couple fresh out of Cleveland State. Each of them had deserved a little booster, as she’d begun to think of it. But none of them stayed long. The cellist, denied first chair in the Cleveland Orchestra, left the city in a cloud of bitterness. The divorcée remarried after a whirlwind four-month romance and moved with her new husband to a brand-new McMansion in Lakewood. And the young couple, who had seemed so sincere, so devoted, and so deeply in love, had quarreled irreparably and separated after a mere eighteen months, leaving a broken lease, some shattered vases, and three cracked spots in the wall, head-high, where those vases had shattered.

Moody, listening to his mother describe their new tenants, was intrigued less by the artist than by the mention of the “brilliant” daughter just his age.

It was a lesson, Mrs. Richardson had decided. This time she would be more careful. She asked Mr. Yang to patch the plaster and took her time finding a new tenant, the right sort of tenant. 18432 Winslow Road Up sat empty for nearly six months until Mia Warren and her daughter came along. A single mother, well spoken, artistic, raising a daughter who was polite and fairly pretty and possibly brilliant. It gave her immense satisfaction to imagine this woman and her daughter settling into the apartment, Pearl doing her homework at the kitchen table, Mia perhaps working on a painting or a sculpture — for she had not mentioned her exact medium — in the enclosed porch overlooking the backyard.

Moody, listening to his mother describe their new tenants, was intrigued less by the artist than by the mention of the “brilliant” daughter just his age. A few days after Mia and Pearl moved in, his curiosity got the better of him. As always, he took his bike. Nobody biked in Shaker Heights, just as nobody took the bus: You either drove or somebody drove you; it was a town built for cars and for people who had cars. Moody biked. He wouldn’t be sixteen until spring, and he never asked Lexie or Trip to drive him anywhere if he could help it.

In front of the house, Pearl was carefully arranging the pieces of a wooden bed on the front lawn. Moody, gliding to a stop across the street, saw a slender girl in a long, crinkly skirt and a loose T-shirt with a message he couldn’t quite read. Her hair was long and curly and hung in a thick braid down her back and gave the impression of straining to burst free. She had laid the headboard down flat near the flowerbeds that bordered the house, with the side rails below it and the slats to either side in neat rows, like ribs. It was as if the bed had drawn a deep breath and then gracefully flattened itself into the grass. Moody watched, half hidden by a tree, as she picked her way around to the Rabbit, which sat in the driveway with its doors thrown wide, and extracted the footboard from the backseat. He wondered what kind of Tetris they had done to fit all the pieces of the bed into such a small car. Her feet were bare as she crossed the lawn to set the footboard into place. Then, to his bemusement, she stepped into the empty rectangle in the center, where the mattress belonged, and flopped down on her back.

Later, when Moody saw the finished photos, he thought at first that Pearl looked like a delicate fossil, something caught for millennia in the skeleton belly of a prehistoric beast.

On the second story of the house, a window rattled open and Mia’s head peered out. “All there?”

“Two slats missing,” Pearl called back.

“We’ll replace them. No, wait, stay there. Don’t move.” Mia’s head disappeared again. In a moment she reappeared holding a camera, a real camera, with a thick lens like a big tin can. Pearl stayed just as she was, staring up at the half-clouded sky, and Mia leaned out almost to the waist, angling for the right shot. Moody held his breath, afraid the camera might slip from her hands onto her daughter’s trusting upturned face, that she might tumble over the sill herself and come crashing down into the grass. None of this happened. Mia’s head tilted this way and that, framing the scene below in her viewfinder. The camera hid her face, hid everything but her hair, piled in a frizzy swirl atop her head like a dark halo. Later, when Moody saw the finished photos, he thought at first that Pearl looked like a delicate fossil, something caught for millennia in the skeleton belly of a prehistoric beast. Then he thought she looked like an angel resting with her wings spread out behind her. And then, after a moment, she looked simply like a girl asleep in a lush green bed, waiting for her lover to lie down beside her.

“All right,” Mia called down. “Got it.” She slid back inside, and Pearl sat up and looked across the street, directly at Moody, and his heart jumped.

“You want to help?” she said. “Or just stand there?” ●

Celeste Ng grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Shaker Heights, Ohio. She attended Harvard University and earned an MFA from the University of Michigan. Her debut novel, Everything I Never Told You, won the Massachusetts Book Award, the Asian/Pacific American Award for Literature and the ALA’s Alex Award. She is a 2016 NEA fellow, and she lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

To learn more about Little Fires Everywhere, click here.