As death rates from painkillers spike across the country, many experts are trying to stop the problem at its source: the doctor’s office.

Last month, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker proposed much tighter restrictions on how doctors can prescribe opioids. Since 2012, Massachusetts and 23 other states have passed laws requiring doctors to, under certain circumstances, check patients’ names in databases that track how and where they fill prescriptions for controlled substances.

And now a new report, released on Monday morning by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, says that doctors in every state should be required to use these databases, also known as “prescription drug monitoring programs,” or PDMPs.

“We are in the middle of an opioid epidemic in this country,” Van Ingram, executive director of the Kentucky Office of Drug Control Policy and one of the authors of the new report, told BuzzFeed News. “Is mandating PDMP use going to wipe out the problem? No. But it’s another tool at our disposal.”

Other experts agree that increased use of these monitoring programs is an important part of the fight against overdose deaths and addiction.

“There’s growing evidence that PDMPs are effective tools in addressing prescription drug abuse,” Cynthia Reilly, director of the Prescription Drug Abuse Project at The Pew Charitable Trusts, told BuzzFeed News. “The focus has shifted to, how do we get the data where it’s needed?”

The first prescription drug monitoring program was instituted in 1939, in California. Today, every state except Missouri has one.

Within a week of dispensing a prescription for controlled substances like opioids or benzodiazepines, pharmacies add the patient’s name and details of the prescription into the database. This allows doctors to look for patterns — in what drugs patients have been getting, how often, and from how many different doctors and pharmacies — that suggest patients are either abusing or selling the drugs.

Because each state has its own laws and databases, PDMP regulations vary widely, both in whether doctors have to check them, and in who else, including private insurance companies and law enforcement agents, has access to the data. Some states proactively send reports to doctors or pharmacies about patients who might be abusing the drugs or the system, as a heads up that the person might need addiction treatment or more cautious prescribing.

In 2012, Kentucky, often considered ground zero for the “pill mills” that have helped drive America’s opioid problem, was the first state to require that doctors search for their patients in the database. According to the law, they have to check the patient’s database record the first time they prescribe that person a controlled substance, and then every three months after that.

So far, evidence suggests that these programs work. Shortly after Kentucky mandated PDMP use among physicians, rates of “doctor-shopping” went down and the number of people seeking addiction treatment went up.

Some doctors are resistant to these laws because the extra steps take time away from their already busy schedules. In Kentucky, the state gives access to other employees in the doctor’s office, so a technician or other staff member can pull a report and add it to patients’ files.

“Initially there was some resistance, but I think that’s dissipated,” Michael Rodman, executive director of the Kentucky medical board, told BuzzFeed News. “By and large, the medical community has really embraced it.”

“I don’t know how many physicians have told me they found patients you’d never believe were diverting meds — maybe the grandmother or the businessman,” Rodman added. “It really opened eyes.”

While these databases are seen as a public health win, they’re controversial because of the potential for law enforcement to go on fishing expeditions (in many states they need an open investigation, but no warrant, to access the data).

In 2014, the ACLU successfully sued the Drug Enforcement Administration because it accessed Oregon’s database without a warrant. A few other states have added a requirement that a judge signs off on law enforcement agents checking PDMP files.

But the Hopkins report argues that increasing law enforcement access to the data is key to slowing opioid abuse.

“In any health crisis or epidemic, there’s a struggle between public health initiatives to tamp down the epidemic, and people’s individual needs and rights,” Peter Kreiner, the principal investigator at the PDMP Center of Excellence at Brandeis University, told BuzzFeed News. “It took a long time, but the public health interests seem to be winning out.”

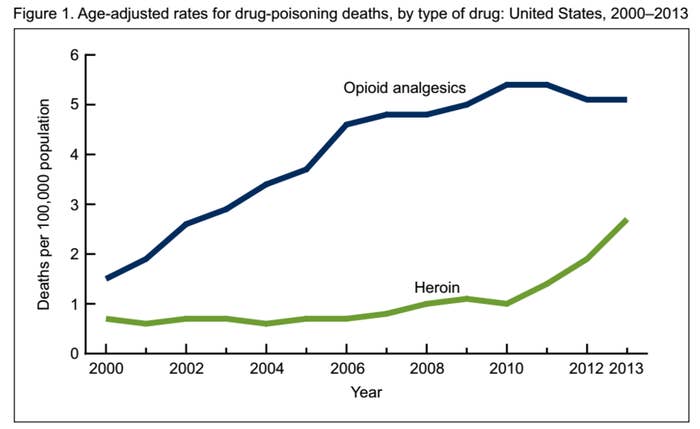

Deaths From Painkillers And Heroin In The U.S.

Still, these programs are not a panacea. The Hopkins report calls for a multi-pronged approach, including increasing access to addiction treatment and distributing overdose prevention kits.

The report also acknowledges that, as with all efforts to curb painkiller prescriptions, the uptick in drug monitoring databases seems to correspond with an increase in heroin use and overdoses, as addicts seek cheaper and easier ways of getting a fix.

Many factors, such as crack-downs on pill mills and new formulations of popular painkillers like Oxycontin, are driving the heroin bump, Kentucky officials told BuzzFeed News.

But PDMPs are also part of this worrisome increase.

“What Kentucky has seen is, although overdose deaths associated with prescription opioids have gone down, heroin has gone up — not enough to offset the decrease of opioids, but a noticeable [effect],” Kreiner told BuzzFeed News. “Until the heroin issue is figured out, then it’s a partial solution.”

UPDATE

This story has been updated to clarify that pharmacists put patient names in these databases, and doctors check their patients' records.