Last year, over 3.8 million babies were born in the US — the lowest number in 30 years. Additionally, fertility rates hit an all-time low.

The birth rate dropped for women in most age groups in the US last year, according to a new birth data report from the CDC's National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Researchers do not know exactly why or whether this is the start of a long-term change.

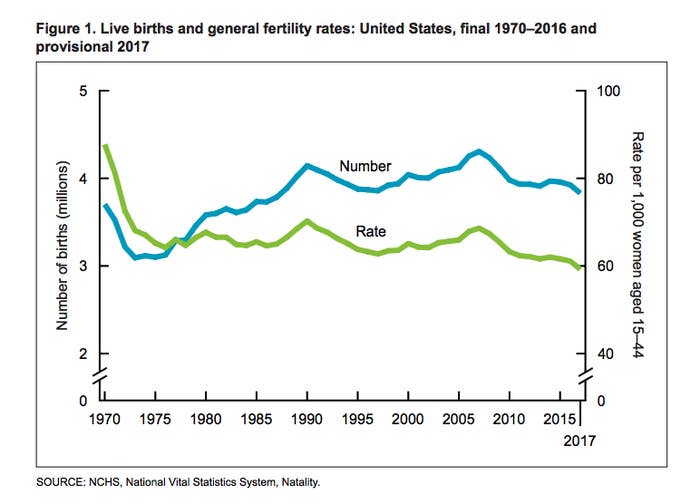

The general fertility rate — the number of births per 1,000 women of childbearing age (defined as 15 to 44) — was 60.2, which was down 3% from 2016 and an all-time low for the US. "This is a pretty big decline since the recession [from 2007–09], when the number was closer to 69 or 70 births," Gretchen Livingston, a senior researcher at the Pew Research Center and an expert on fertility and demographics, told BuzzFeed News.

Researchers use the general fertility rate to measure the changes in childbearing during a given period or over time. "This information allows you to better understand what your population will look like in 10 or 20 years so you can forecast what the workforce would look like, demand for educational facilities, and resources," Brady E. Hamilton, coauthor of the report and researcher at the National Center for Health Statistics, told BuzzFeed News.

But a dip in the birth rate over one period of time isn't necessarily a dire sign for a country's population and economic growth. And a decline in the fertility rate doesn't mean that something biological is happening like it was in The Handmaid's Tale.

The fertility rate in the US has actually been declining for decades, mostly among women in their teens and twenties.

The US fertility rate took a nosedive in the 1970s and has fluctuated since, dropping again in 2008 during the recession. The rate has continued to drop since, with the exception of a small increase in 2014. "Fertility rates in the US have actually been on a decline for decades — the declines may have gotten steeper, but we're mostly seeing a continuation of long-term trends," Livingston said.

The groups that experienced the largest declines in birth rates from 2016 were younger teenagers ages 15 to 17 and older teenagers ages 18 to 19 — they had 11% and 6% decreases, respectively. These declines are in part due to policies and programs aimed at reducing teenage pregnancy, Hamilton said. The number of births also fell for women in their twenties (by about 4%–5%).

Women in their thirties, who have the highest birth rates, had small declines last year after rising steadily from 2012 to 2016. By contrast, the birth rate increased by 2% for women ages 40 to 44, and the number of births rose by 3% among women ages 44 to 49. Despite the overall decline in birth and fertility rates in the US, more older women are having children than before.

Experts point to the fact that more women are delaying having children to pursue an education and advance their careers, and, well, just because they want to.

The report only included data from birth certificates, so there wasn't information on the decisions and beliefs around having children, Hamilton said. The fertility rate could decrease for a number of reasons, but the experts speculate that postponement is probably a major factor.

Women are now much more likely to get an education and join the labor force than they were in previous decades, and to delay or skip childbearing just because they want to. "People are trying to get their career set up first before having children or completing their family," Livingston said.

Contraceptives could also play a role, Livingston said, because there are an increasing number of long-term options, such as hormonal IUDs, to help women manage their reproductive life. (If they choose to have one and if they are heterosexual.) "Some of these births are not forgone, they are simply postponed," Hamilton said.

So the drop in birth rates in 2017 doesn't necessarily mean fewer women are having children — it could just mean that people currently in their childbearing years (basically, millennials) are not having children right now, and may or may not decide to have them later on. "Recently, more women have been delaying birth and that can lead to an overstatement at how large the decline in birth rate is in any one year," Livingston said.

Does this mean the US population is shrinking? Probably not — or at least not yet.

The total fertility rate (TFR) — the average number of live births a woman will have in her lifetime — was 1,765 births per 1,000, the lowest since 1978. TFR is often discussed in the context of "replacement level fertility" or the rate at which women have enough children to replace one generation.

If a country has a "replacement rate" of 2.1, that broadly assumes each woman will have two children to replace themselves and a theoretical partner, Livingston explained. The TFR in the US in 2017 was well below 2.1, but it has been below replacement level since 1971, according to the report.

The experts pointed out that the US is still better off than other developed nations like Japan or Italy, which are experiencing negative population growth. "A rate below 2.1 would imply society is shrinking, but we still have new members of society introduced by immigration," Hamilton said. Immigration is an important factor for population growth and increasing the number of people in the workforce so there are enough workers to support an aging population.

Immigrant women account for a disproportionally high share of the US birth rate. "Immigrants make up about 13% of the US population but the share of births to foreign-born mothers is 23%," Livingston said. The TFR is more of a concern in countries that don't have as much immigration as the US.

Researchers can't predict whether the recent declines are a temporary blip or the start of a long-term trend. It's important to remember that the report only includes the birth and fertility rates for a given year, Hamilton said, and these could change over time.