This is the first part of a series on the Colorado river. For Part 2, click here. For Part 3, click here

Bob Martin’s floor-to-ceiling office windows overlooking Lake Powell have become a constant source of stress. For the past seven years, the Glen Canyon Dam field division manager has had a front-row seat watching the water levels of the nation’s second-largest reservoir rapidly shrink.

“People need to realize that this is not like the national deficit where we can just say, 'Well, we’re going to print more money,'” Martin said. “You’re talking about a tangible, finite commodity. It is out of our control to make it rain, or make more water. We need to do something.”

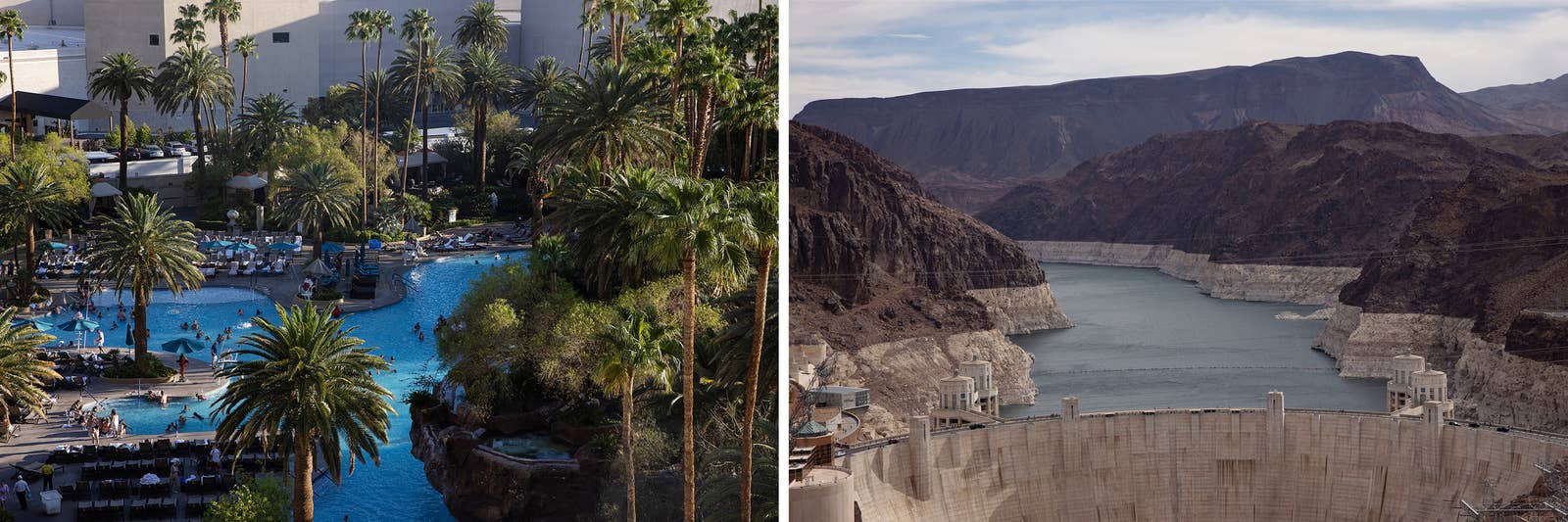

For decades, the Lake Powell and Lake Mead reservoirs, which bracket the Grand Canyon, have been the major savings accounts for water in the Western United States. Built on the Colorado River, the country’s two largest reservoirs have enabled Western farms and cities from Los Angeles to Denver to have a stable water supply throughout a relentless 21-year megadrought. But today, Lake Powell and Lake Mead are hovering at close to 33% of their full capacity, historic lows not seen since the dams were first built. If water levels drop to 22% and 15%, respectively, the dams can no longer generate hydropower. If they fall to 8%, they will become "dead pools," meaning water cannot continue being delivered. This would trigger an urgent water crisis for the 40 million people who depend on the Colorado River.

“If, in your personal financial life, your outflow exceeds your inflow, your upkeep will be your downfall,” said Martin. “We're kind of getting to that point now in the system.”

But the current water crisis isn’t only being driven by the megadrought. A century of basing policies and development on an overestimate of how much water was actually in the Colorado River to begin with — and betting on more years with heavy snow and rainfall — started us on the path toward our current water shortages. And the last two decades of megadrought in the Southwest — amplified by a warming climate — have hit the fast-forward button.

River managers and policymakers have until 2026 to replace temporary drought contingency plans with a long-term plan for the river that replenishes, rather than drains, the reservoirs. What they decide has implications for almost every major Western city, 30 Native American tribes, 5.5 million acres of farmland, and northern Mexico.

For most people, the deepening white bathtub rings around Western reservoirs have come to symbolize the drought. For Martin and a growing number of scientists, policymakers, and water managers working to solve the crisis, the rings are a reminder of how people are failing to acknowledge that we are collectively using water in a way that is causing the Colorado River to run dry.

Water is running out in part because of a century of overpromising it.

Ninety-nine years ago, seven Western states came to an agreement to share the Colorado River. Known as the 1922 Colorado River Compact, the plan split the river at Lees Ferry, a point just north of the Grand Canyon, into the “upper basin” states of Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and New Mexico and the “lower basin” states of Nevada, Arizona, and California.

But the compact failed to include water allocations for the 30 sovereign Native American tribes that have inhabited the Colorado River Basin for centuries, for Mexico, whose northernmost states depend on the river for agriculture, or for the wild plants and animals that rely on the river water to survive.

Perhaps most dangerously, because it calculated the river's volume using data collected during an abnormally wet historical period, the compact effectively promised the people of the Colorado River Basin more water each year than would actually exist. While temporary drought contingency plans have recently been implemented, for the last 100 years, the core assumption of how much water is available has not been altered to reflect reality, setting the seven states that share the river on a path where people’s demand for water would inevitably outpace supply.

“Politicians have overpromised how much water could be developed in the basin since the 1920s,” said Eric Kuhn, who coauthored a book chronicling how policymakers have ignored scientific assessments of the Colorado River when findings did not support proposed development projects. “This is a crisis that would have happened without climate change — climate change is just adding insult to the injury.”

In the 20th century, building infrastructure projects to move Colorado River water to cities and farms and relying on water collected during years with more precipitation took precedence over making difficult decisions to curb water usage. That trend continues today, with the 2020 US census showing that Utah, Nevada, and Arizona — which all rely on river water — are in the top 10 fastest-growing states in the country, even though they’re also among the driest.

That there is less river water to divide in reality than what is allocated on paper is not a message residents in desert climates or their politicians want to hear, since access to water enables development. But some scientists argue the megadrought is not temporary and is instead a sign of a longer-term drying out of the region. That raises questions about how much the river will shrink in the future, and exactly how much — and where — we need to curb demand.

“Given the fact that the reservoirs are a third full, you’re asking for a really hard, difficult, unprecedented conversation with a ticking clock,” said Jack Schmidt, a river scientist at Utah State University. “We are in a crisis now. Let’s not kid ourselves. The question is, how intense does that crisis get? Everything we are seeing suggests there may not be enough time for the incremental approach to change, which has always worked in the past.”

The last two decades are the driest the Colorado River Basin has been in 1,200 years.

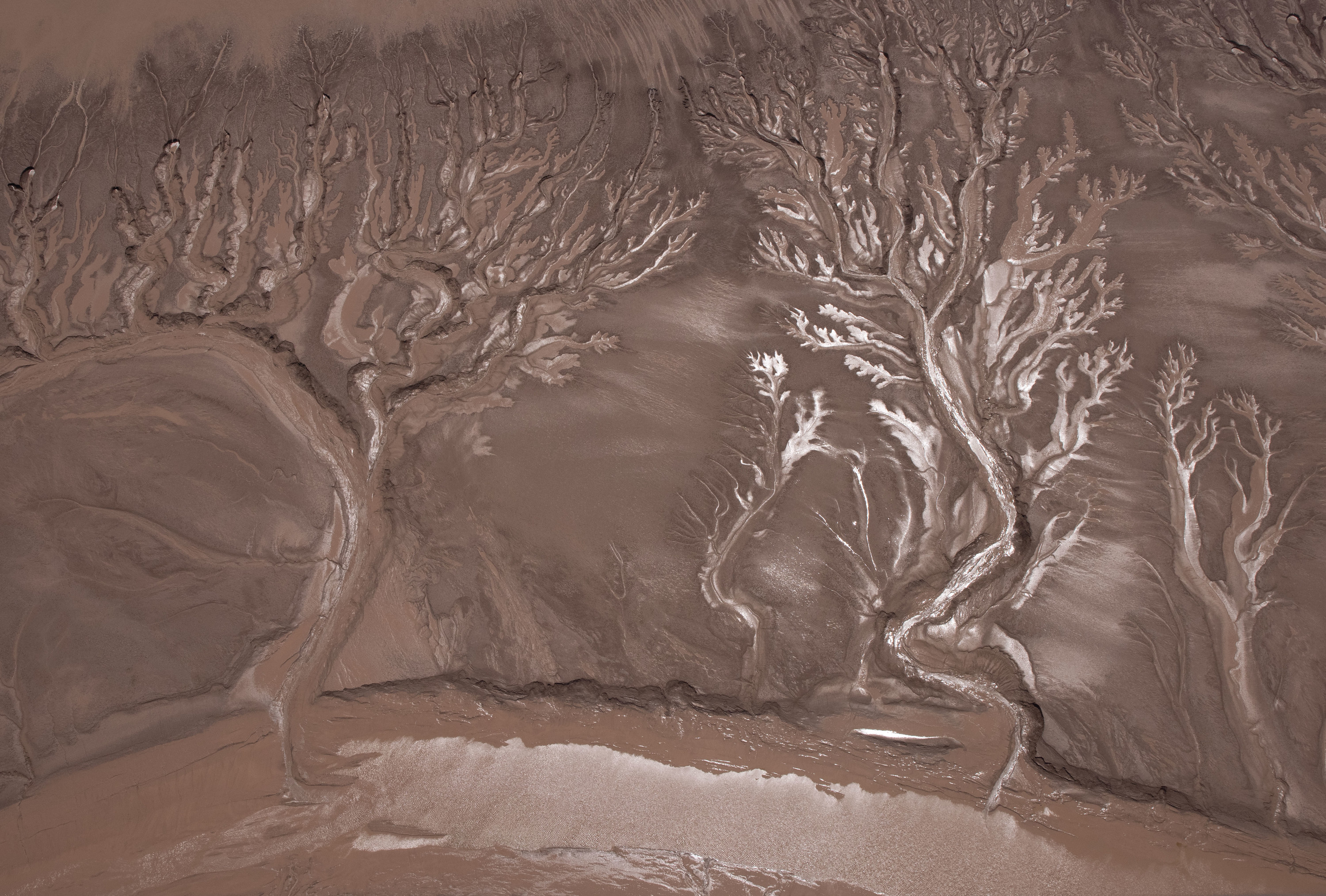

Roughly 50% to 80% of the Colorado River’s water comes from snowpack that accumulates high in the Rocky Mountains. To figure out how much snow there is each year, hundreds of snow monitoring sites are set up throughout the mountain ranges, which are maintained by a network of snow surveyors who hike, snowmobile, ski, and snowshoe hundreds of miles collecting critical data.

“What we do is based on the simple fact that the majority of water in the Western US comes from mountain snowmelt,” said USDA snow surveyor Brian Domonkos, who has observed mountain snowpack for 17 years. (Domonkos loves the river systems he monitors so much, he’s in the process of getting them tattooed on his arm.)

The data collected by Domonkos and his colleagues allows researchers to generate water forecasts to estimate how much water will be available for use throughout the year.

“If ebbs and flows in basin snowpack over the long term are below normal, you’re going to have an overall deficit of water,” said Domonkos, explaining how consecutive dry years lead to dry soil and low stream flows, which make it hard for the river to bounce back. “We’re finding that even if you were to have normal snowpack years back to back, it’s probably not going to wipe away that deficit.”

While the Colorado River has cycled through wet and dry years, the last two decades are the driest the basin has seen in 1,200 years.

“We can look back thousands of years with tree rings and see that this drought is exceptional,” said Kevin Anchukaitis, a paleoclimatologist at the University of Arizona’s Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, where researchers have reconstructed historical flows of the river dating back to the 1100s. “We know there is a lot of natural variability in rainfall within the Colorado River Basin. But knowing the range — how wet can it get? How dry can it get? How long can it be dry? — is important for models they're using to predict the future of the river.”

Other studies looking at the future suggest climate change is only going to make the West hotter and drier.

“As warming continues, the Colorado River will continue to shrink,” said Colorado State University senior water and climate scientist Brad Udall, who has spent years studying how hotter temperatures are impacting natural inflows of water to the Colorado River. His research indicates that for every degree Celsius that the temperature increases, the Colorado River loses 3 to 10% of its natural inflow. A 2020 study by US Geological Survey hydrologists was more grim, setting losses at 9.3% per degree Celsius of temperature increase.

“Stabilizing this system during a period of declining flows is going to involve reducing our demands and having robust plans in place,” said Udall. “Specificity is where it gets tough.”

The shrinking water supply is causing growing tension among states.

From 1906 to 2019, the average annual natural flow of the Colorado River was 14.8 million acre-feet a year. (That’s a lot of water. Each acre-foot is roughly equal to 326,000 gallons.) The 1922 compact assumes at least 15 million acre-feet of water will be available each year, apportioning 7.5 million acre-feet to the upper and lower basins each. Importantly, the agreement also states that the upper basin cannot deplete the river’s flow to levels that prevent delivery of the lower basin’s share.

But now that math is getting harder. In the last two decades, the river’s natural flow has averaged closer to 12.4 million acre-feet per year. The problem gets worse when you add a 1944 treaty that guaranteed Mexico 1.5 million acre-feet of water each year and the 3.2 million acre-feet of water that states must legally share with Native American tribes within the basin, a majority of which have water rights that predate the compact under a 1908 Supreme Court ruling.

“You’re in the highest-stakes poker game you ever could imagine,” said Schmidt, explaining mounting tensions among states over water rights.

While the upper basin states of Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, and Wyoming collectively use an average of just under 4 million acre-feet of water annually, the lower basin states of California, Arizona, and Nevada are already using their full 7.5 million acre-feet allotment. Many tribal water rights remain unused due to prolonged legal battles and a lack of infrastructure.

“When you’re talking about cutting water coming out of somebody’s spigot, or cutting somebody’s hopes and dreams, something's got to give,” said Schmidt. “That means really hard-nosed negotiations are going to have to be made to redistribute water.”

The crisis raises difficult questions. What is a fair way for the upper and lower basins to share the burden of less water? Within states, how will we decide the “best” or most “beneficial” use of water — is growing crops more important than expanding major cities? How will states honor water rights of Native Americans who have largely been excluded from water deals?

In July, federal officials took unprecedented emergency action to stabilize water levels at Lake Powell, releasing water from smaller upstream reservoirs. This allows Powell to continue generating hydropower, but it’s a temporary solution: Releases are only scheduled through December. Deeper cuts for 2022 are expected to be announced in mid-August, which will affect Arizona, Nevada, and Mexico, all states that signed agreements to cut their water use. But some worrisome projections suggest we could hit reservoir levels that are within 5 feet of triggering even deeper cuts that would affect residents in major cities such as Phoenix.

The only other major water source for most desert states sharing the river is groundwater, a nonrenewable resource. In Arizona, groundwater levels in many counties are already stressed by drought and growing demand. Cochise County, where wells are running dry, provides a glimpse of the types of disruptions that may soon become far more widespread across the West.

“If we’re not properly prepared, this falls on us. This doesn’t fall on nature,” said Udall, who is concerned people aren’t taking the worst-case scenarios seriously. “Because we have the knowledge and we have the data to know a grim future is possible. Failure to plan for this would be a failure of very large proportions.” ●

Aerial photography with the help of Lighthawk Flights.

This is the first part of a series on the Colorado river. For Part 2, click here