It was – literally – a textbook case of executive greed and mismanagement: Senior partners at a high-flying consulting firm sold expensive shares to their own employees, filling their own pockets but putting the firm deep in debt.

The firm -- cited in textbooks like Dirk Halacher’s 2012 “The Governance of Professional Service Firms” -- is Bain & Company, the consulting firm where Mitt Romney spent his formative years in the private sector. And when Romney explains that he’s a “turnaround” specialist, one of the key examples is his success in 1990 and 1991 at saving Bain.

“Mitt returned to his old consulting firm, Bain & Company, as CEO. In a time of financial turmoil at the company, he led a successful turnaround,” reads his official biography.

In Romney's 2004 book “Turnaround,” which focuses on the Salt Lake City Olympics, he writes only that Bain “got in some financial distress” because it was “short of cash and short of new clients.”

Left out of the the official story is why Bain & Company needed a turnaround. It’s a tale Romney has never addressed at length, although it’s one of the signal moments of his career. That may be because of the episode’s ambiguity: Romney was on one hand, indisputably, the heroic technocrat, riding in on a white horse to save the day.

But he was also cleaning up his mentor’s mess, and the unwisely borrowed cash had helped to finance Romney’s own career.

Some details are not clear. Bain & Company’s financials remain private, and many people close to the firm are reluctant to talk. Two Bain veterans, a critic and a Romney defender, both spoke to BuzzFeed on background, reflecting deep differences among alumni of the firm that continue to this day.

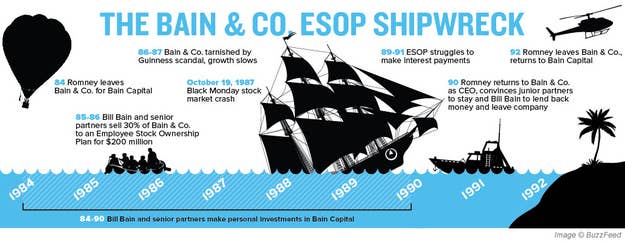

The fatal steps took place in 1985, when the firm’s founder, and Romney’s mentor, Bill Bain, and a core group of partners reportedly believed they weren’t taking home the kind of money that their status atop a fast-growing business merited. Bain & Company was high-flying and glamorous, with an aggressive approach and a penchant for secrecy that earned it the largely admiring sobriquet, “The KGB of consultants.” But consulting firms, utterly dependent on their personnel, are typically hard to sell, and difficult places to build equity. And with no arms-length buyer at hand, Bain and seven senior partners decided to sell the firm to their own employees.

“Bill Bain put this in place largely in secret,” former Forbes managing editor Walter Kiechel wrote in his recent “The Lords of Strategy.” The top managers sought outside valuations, and they got one they liked. Without consulting the junior employees who would hold the company stock, senior managers reportedly valued 30% of the firm’s equity at $200 million, and sold it to a vehicle called an Employee Stock Ownership Plan. The ESOP borrowed to buy the equity, and would reportedly be on the hook for annual payments around $25 million.

“Most of the people other than the partner group at Bain considered it to be a very greedy move on the part of Bill Bain and the founding partners, particularly the fact that they didn’t tell the other [junior] partners about it,” Kiechel said in an interview.

The senior partners had cast the move as a favor to junior employees, an opportunity for them to share in the firm’s profits.

A former Bain employee had a blunter take on the stock: The top partners “shove[d] it down our throats.”

It is now a case study in what not to do.

“If the firm value is based on optimistic future growth projections, this may leave the firm in a vulnerable position, which is what happened at Bain & Company in the late 1980s,” says Halacher’s industry textbook.

As for Romney, he had formally left the firm about a year before the move, with Bain’s personal blessing, to start a sister company, Bain Capital. That meant he wasn’t involved in creating the ESOP, and didn’t personally profit from it; if he shared private opinions on the scheme at the time, they have not been revealed. (A Romney spokeswoman, Andrea Saul, declined to comment on the episode.)

But Romney’s career did depend, if indirectly, on the ESOP deal.

“While Bain Capital was its own firm, independent of Bain & Company, Bill Bain and many of his partners had invested in every fund the private equity outfit had raised, reaping terrific returns,” Keichel writes. That money didn’t go into Romney’s first fund – Bain Capital was up and running in 1984, before the 1985 and 1986 ESOPs. But Romney kept raising and investing money through the decade, and the money came from Bill Bain and his partners – whose own wealth came in part from the disastrous ESOP.

The crunch began in 1986, when two Bain consultants were accused – and ultimately convicted – of manipulating stocks in the course of takeover effort by their client, Guinness, of a distillery company. Bain was never accused of wrongdoing, but the episode – combined with a weakening economy – tarnished the firm’s brand and slowed its growth.

Soon the ESOP was struggling to meet its interest payments. By 1990, the cash crunch was desperate, producing a deep divide emerged in the company, according to contemporary reports and former staffers. The partners who had profited from the ESOP argued (as they continue to) that they’d simply been trying to share ownership more broadly. The junior partners, whose earnings had been going to service $25 million in annual interest payments and whose stock was illiquid and likely worthless, felt like they’d been had.

Romney writes in "Turnaround," his 2004 book, that he focused on cutting costs, but others’ accounts paint his key role as a political one: He bridged the divide between embattled senior partners and angry junior ones. He’d been technically out of the firm for six years, though he remained close to its top management and even shared office space for a time. And after a series of tense meetings with both camps, he succeeded brilliantly: He talked Bill Bain and the top partners into lending back millions from their personal fortunes to the firm; and he talked the junior partners – whose work was the firm’s value – to stay, in exchange for real ownership stakes and a new, transparent management.

Romney’s “key task was to commit the people, the team, to stay with the firm during the turnaround and to work in lock-step together to get the company back on track,” he wrote in “Turnaround.”

(Romney spokeswoman Andrea Saul did not comment for the story, but directed a reporter to some of the relevant passages in "Turnaround.")

But the ESOP meltdown “left behind a legacy of bitterness that endured for years,” Keichel wrote. Bill Bain, who gave the firm its name, wasn’t invited back to speak at a meeting of the firm for a decade – and even then it was over the objections of some partners.

Romney, however, had succeeded in winning over both sides. Though Bain had been forced out, he remains loyal to his protégé: He gave the maximum contribution to Romney’s 2008 campaign, and again to his 2012 bid, writing a check for $2,500 last May.