THOUSAND OAKS, California — Adjusting an elderly woman's wheelchair so she could be closer to the window, Audrey Galvan said she was afraid of slowing down, because that would mean she was going to have to process the last 72 hours.

Thousand Oaks, California, where the 25-year-old grew up, is at the nexus of two wrenching and historic disasters: a mass shooting at a beloved country-western bar and this weekend’s massively destructive wildfire.

On Thursday night, barely 24 hours after a gunman barged into the Borderline Bar and Grill and killed 12 people, powerful winds flung the fast-moving Woolsey fire along the hills and down into the suburban neighborhoods, filling culs-de-sac with swirling embers and thick plumes of ash.

“It’s been a brutal, hellish three days for the city of Thousand Oaks,” said Thousand Oaks city council member Claudia Bill-de la Peña during a press conference on Saturday morning.

Galvan lost a good friend in the Borderline shooting and, like much of the community, had barely begun to mourn before evacuation alerts lit up her phone, presenting her with another crisis.

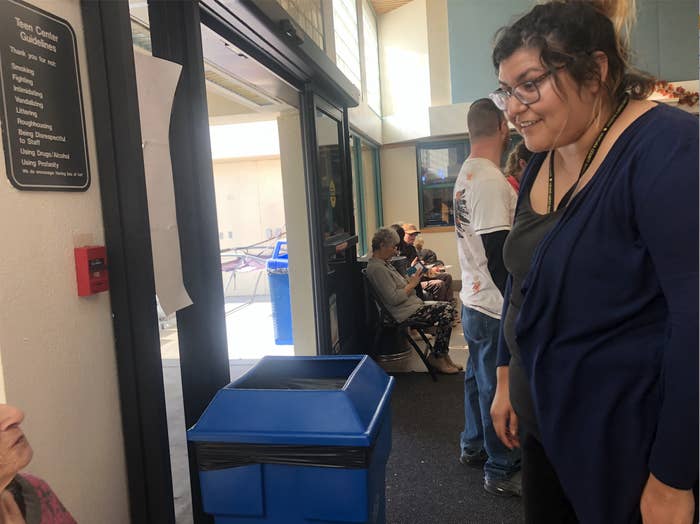

“How do you have time to plan memorials for people? We went from a massacre to a natural disaster and no one has any time to catch their breath,” Galvan said, leaning against a white concrete ledge outside the Thousand Oaks Teen Center Saturday afternoon. “You can't grieve or feel anything when you're being kicked out of your home.”

She had been at the volunteer center for about 48 hours straight. Everything before it felt like a blur. She got off work late Thursday night from her nannying job in nearby Woodland Hills but couldn't get home because the roads were closed.

"The fire," she said. "I had forgotten that was happening."

She went to her friend Nancy Aguilar's house to stay the night. At 11:30 p.m., they got the buzzing emergency alert on their phones to evacuate.

As the quiet hours of Thursday seeped into Friday, the sky and hills above Thousand Oaks turned deep orange. An endless gale of sirens pierced the wind as authorities careened around neighborhoods, telling people to evacuate immediately, as their homes quickly became threatened by the inferno.

Thirty minutes later, Aguilar, who works with the Red Cross, was called in to help transition the teen center into an evacuation shelter. Not knowing where else to go, Galvan joined her.

The center's kitchen still had plastic containers of croissants and boxes of Lipton tea bags because, 24 hours earlier, it had transformed into a family reunification center as parents and other members of the community frantically tried to get in touch with loved ones after the Borderline shooting.

Around 3 a.m. on Friday morning, the teen center began to fill up again, but with dazed and weary families in pajamas, carrying pets, pillows, plastic bags filled with passports, and other possessions.

A few miles away, yellow police tape and dark FBI vans still blocked off the Borderline Bar and Grill. A small group of friends, one wearing a Vegas Strong T-shirt, two others in cowboy boots, stood under the shade on the other side, hoping to retrieve a purse and stroller that they left behind after fleeing through a broken window.

Borderline is much more than a bar. It hosts all-ages concerts, birthday parties, line dancing lessons, and a weekly college night. Galvan went to the country night at Borderline with her friends, where she frequently danced next to Alaina Housley, one of the shooting victims, who Galvan said was "always there." The drinks were cheap and generous.

"There's really not much to do here, so that's why we go to Borderline," Galvan said. "You knew the girl's mom who checked you in. You saw the same people at the pool table every week. You knew the artists who would come and sing."

Thousand Oaks resident Matt Edwards was also struggling to digest it all. He had driven to the teen center Friday morning with his mother and aunt, after cramming their old Toyota full of their belongings.

The last few days have “felt dreamlike,” Edwards said.

He said he’d come off a 14-hour shift as a bakery manager at a Ralph’s grocery store, covering for a coworker whose friend had died at Borderline. "Now here I am standing in my pajamas because of a fire," he said. "It's surreal and such a double whammy. What's next? Is there going to be an earthquake?"

Inside the shelter, Galvan continued to check in evacuees, her black hair frizzy and sticking out from her bun because, like so many others, she cannot remember the last time she showered.

Handing out water bottles, directing high schoolers carrying in bags of donated food, and refilling white styrofoam cups with coffee helps keep her mind off Borderline and her friends' texts talking about it.

"The adrenaline when you jump in and see what people need. You just want to make sure they're OK. You see them at the grocery store, you know?" Galvan said.

With their streets roped off and backyards now charred and blackened, dazed Thousand Oaks residents order coffee at a Starbucks filled with firefighters, pump gas at any station that’s still open, and readjust their white face masks to try to keep out the acrid air that has coated their community for the past few days.

At Cal Lutheran University, whose campus became the nexus for grieving community members after the shooting, stunned students had to quickly transition into a role that, growing up here, has become second nature: helping their family evacuate their childhood homes.

Jordan Erickson, a junior who sang choir with Justin Meek, who died in the shooting, left campus Friday to help his parents pack up. He texted Sunday that their home was OK.

"Our community isn't going to forget the shooting," Erickson said. "It hit so close to home everyone knew someone who knew someone who died. It’s a difficult time but the fires won’t detract from the grief that our community is going through. It’s just a lot in such a short span of time but we’ll never forget."

The teeming teen center had quieted down by late Saturday afternoon, though people carrying donated pillows, bananas, and dinners continued to stream in.

After becoming a pro at "power naps," Galvan felt ready to go see her parents, shower, and sleep. She still didn't really want to talk about the shooting, or her friend, and has dozens of texts she doesn't want to open or have the energy to read.

"It's so weird to think how we are all going along and dealing with all this," she said. "I put the emotions aside and let the adrenaline kick in and I'm kind of scared how it will feel when it stops."