“We almost decided that we shouldn’t show it to you.”

Eugene Chung is standing in his office, hesitating. Really, he’s standing in a desk-filled condo in a residential building, but here in San Francisco’s fog-soused, startup-heavy Soma neighborhood, all that steel and glass blends together, so we’ll call it an office. And really, he’s not so much hesitating as explaining himself, managing expectations, doing the nervous dance of a perfectionist who’s not quite ready to share what he’s made with the world.

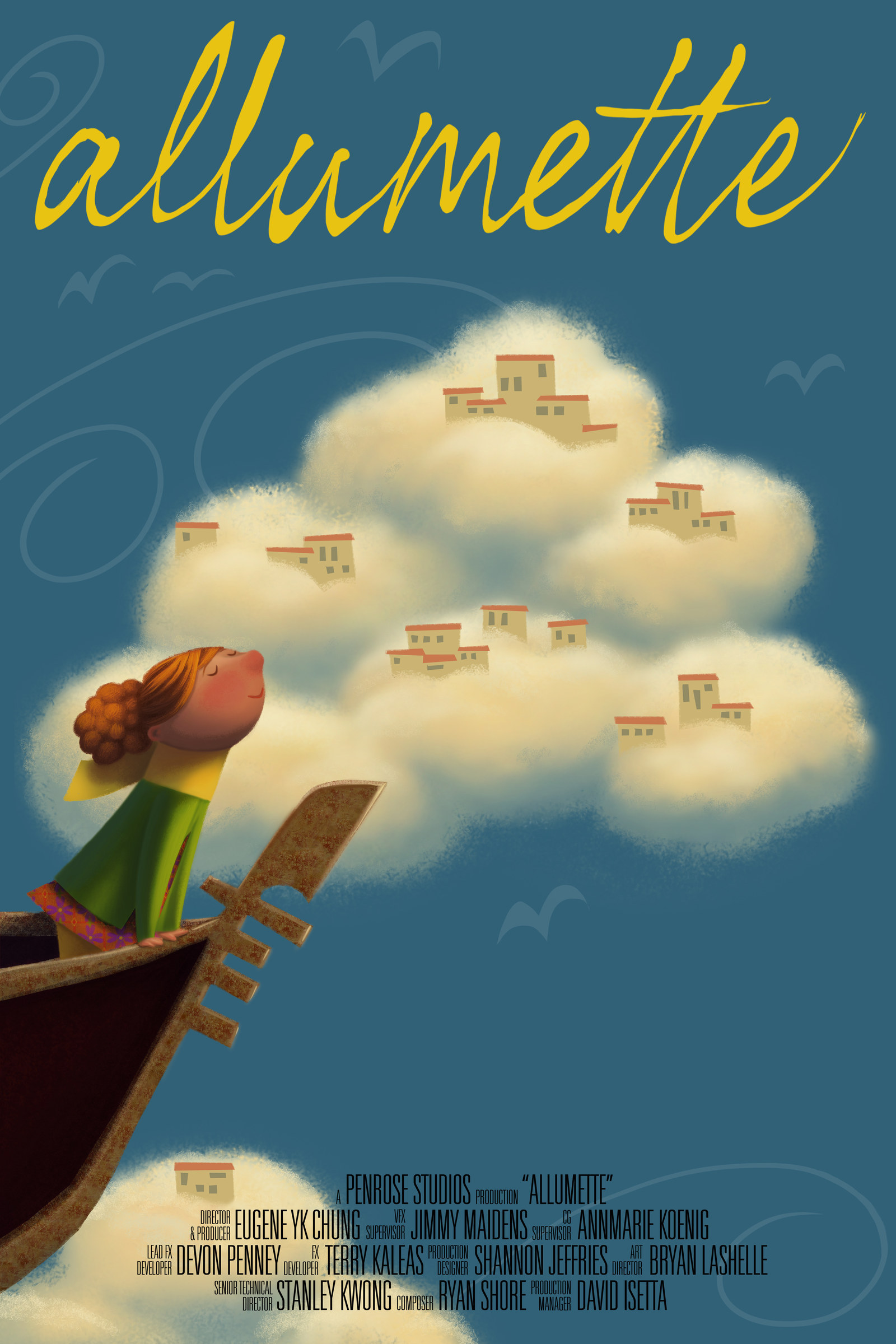

What he’s made is "Allumette", a 10-minute virtual reality movie about an unnamed orphan girl in a floating city. This studio full of 15 animators and designers and engineers has been working on it for the past six-odd months. They’re called Penrose. They’re nervous. The next day, the year-old studio will head to Sundance, where they’ll be making the rounds, showing "Allumette" in private meetings with various movers and shakers, and screening The Rose and I, an earlier work, publicly as part of the festival’s New Frontier showcase.

New Frontier started as an exhibit for experimental film techniques, but in recent years, it has become colonized by virtual reality. This year — the year many hope will be the one that takes VR from a tech-y curiosity to a mainstream pursuit — there are 31 VR experiences at New Frontier.

That's huge, and it's illustrative of the inflection point virtual reality is at right now. The headsets are coming soon, and they’re great. What VR needs, desperately, is things to fill the headsets with. That content is coming; artists and filmmakers and techies and startups and investors all see the same opportunity. Games will be first, goes the industry logic, but narratives — the movies and TV shows and whatever else they can drop a viewer into — are what will take this mainstream.

But VR is currently manned almost entirely by technologists, not artists, so there’s a hunt for storytellers — good ones. And, of all of them, Chung, the founder of Penrose and, to date, its sole director (in the filmmaking sense, although the title works in the executive sense as well), might have the most impressive bona fides: He worked on production at Pixar before founding Oculus’s Story Studio — the arm of the VR giant that makes narrative experiences — as the company’s head of film & media. Now he’s struck out on his own to form a studio with complete editorial independence, no allegiances to a single headset or platform, and a team culled from places like Pixar and Dreamworks.

Chung stands a little below average height, with hair long enough that he periodically sweeps it off his forehead during conversation. He has a penchant for slim-fitting sweaters and cool shoes and, like his films, is unfailingly put together and incredibly detailed-oriented. (When he heard a BuzzFeed photographer was coming to the office, he instructed the Penrose staffers to wear solid colors so the pictures would turn out better.) In a field made up largely of computer scientists obsessed with testing the technical limits of this latest, greatest gadget, he’s an unabashed aesthete, the kind of person who casually drops references to Bertolucci and Dostoyevsky in conversation.

The rest of Penrose seems to share Chung’s sensibility. For the entirety of its production, "Allumette" has been known around the office as "Rope", after the Hitchcock film of the same name. When it was first conceived, the studio decided it would be made without cuts — the hallmark of the original Rope. The plan didn’t stick, but it speaks to the ambition of the studio: It's clear that Penrose is gunning to be included in a canon.

The problem is, for VR right now, there isn’t any canon to speak of, and the rules to entry aren’t going to be clear for quite some time. Chung may be well-positioned to become the medium’s first auteur, but to do that he has to figure out what makes for a VR classic before anyone else.

Ultimately, Chung decides that "Allumette" is ready to show. Close enough, at least. But he’s quick to point out that it’s not a movie, it’s a trailer — a 10-minute-long, narrative trailer that doesn’t exactly give an idea of what the movie is about so much as drop the viewer into a world and let them look around before starting a story and jerking them out once things get moving. It is, essentially, a Sundance-worthy short film: breathtaking, ambitious, a little confusing.

It’s certainly not a trailer in the traditional sense of the word. But Chung — like Penrose as a studio — is a perfectionist, and the prevailing sense of the office is that everything, no matter how long it’s been in production, is a work in progress. The product can always be better. They call "Allumette" a trailer because, even in its polished state and despite its ability to wow viewers, they don’t consider it finished.

"Allumette" takes place in a cobblestone-paved city dominated by canals. It’s based on Venice but it’s in the sky, the waterways replaced with clouds. The protagonist is a young girl, alone, dragging a suitcase behind her. She settles on a corner and opens the case. In it are three long matches, almost as tall as her, each one a different color. She strikes one and it glows, iridescent, brighter until it takes up your entire field of view and all you can see is a gold that brightens into a white screen.

When the light from the match fades, you see empty sky filled with clouds, and a ship, powered by clockwork gears, flying across it. The match girl has a mother in this scene, and when they dock in the city they sell a match to a pedestrian. The scene fades, back to the little match girl alone again, at night, where she strikes another match.

The perspective through which all of this is viewed is important. "Allumette" and The Rose and I — Penrose’s first feature — both do something unusual for virtual reality movies, which is take the viewer a step back from the experience. To date, most VR sets and experiences have been designed for first-person viewing. But Penrose’s style — inasmuch as a studio can have a style after just two pieces — is to disregard the first person. In both The Rose and I and "Allumette", the viewer is much, much bigger than the story — a disembodied person in space with the story playing out in miniature in front of them.

It works a lot like the third person in a book. You’re reading the book, but it’s from a perspective where you can see all the characters at once. Like a book, "Allumette" doesn’t make you think too hard about this. You can still relate, obviously, get caught up in the action, and identify with the characters. In VR you just notice the strangeness of perspective a little more.

The approach isn’t all that different than a standard, 2D movie, but in VR, it’s almost heretical. Penrose is breaking the fundamental promise of VR — to put you in another person’s shoes. This kind of approach has been trumpeted at length by the most visible people working in the field. Chris Milk, creator of the app/platform/production studio Vrse and longtime VR evangelist — he was recently the subject of a Vanity Fair profile touting him as “virtual reality’s first auteur” — calls the medium an “empathy engine.”

The problem is, this doesn’t work. At least not for storytelling.

Right now, a foundational tenet of virtual reality is the concept of presence. How realistic can each headset make a new world? How does each experience pull you in, make everything feel real? How in the moment are you? Presence is discussed as if it's a quantifiable metric, and, because it’s the true differentiating factor between VR and film — VR is the one you can actually live in — it’s considered by many in the field to be the most important quality. So much so that some enthusiasts capitalize it in writing: Presence.

But there are a few major problems with this. The first is a fundamental one. It's virtual reality, not reality, and at some point you're going to run up against that. You can’t lean against a table in VR and not fall over in your living room — there are limits to how realistic this can all get, and at some point the sense of presence has to be broken.

The second problem is that presence is fundamentally at odds with storytelling. “Presence is the holy grail of VR,” says Chung, “but when you feel present it’s hard to absorb a story.” Stories require attention — good ones have characters and plot and dynamism. Presence requires only existence. The things that you’re in the moment for, the thing some virtual reality enthusiasts and creators are striving for, is an experience that you’re unable to separate from real life, which makes it hard to also absorb a story. It would be like trying to listen to Serial while having sex.

“There’s a really interesting identity question in VR. Who are you in the experience? It’s a difficult question to answer,” says Chung. “There was one idea we had early on that you’re a ghost. Or a comatose person — a Diving Bell and the Butterfly–type effect. But if you are trying to tell a story, there’s a problem of identity.When you change the scale of the story, you skirt that problem. You don’t have to wonder who you are.”

The Rose and I takes place in space — the little prince, from the classic French children’s story, lives on another planet and finds a rose that is coughing. He goes inside, finds a watering can, and waters the rose. In most VR experiences, the viewer would be one of the two characters: the prince or the rose. Instead, the entire planet is about the size of a beach ball, the prince inches tall. Instead of being one of the characters, the viewer is a kind of director, deciding where to watch from.

The choice appears to have paid off in the case of The Rose and I. “They made really good use of positional tracking,” says Will Mason, the co-founder and editor-in-chief of UploadVR, a virtual reality trade publication that launched in 2014. “You’re controlling how you’re viewing the story — do you follow the rose or the person? It really added to the storytelling.”

There’s a race going on, but because this is art, no one knows where the finish line is.

Mason says he’s seen too many virtual reality experiences to count, and what Penrose has produced so far ranks “very close to the top.”

And Shari Frilot, a senior programmer for Sundance and the curator (and co-founder) of New Frontier, says The Rose And I “still stands out from the pack.”

“The craft of it is so great, and its approach is so unique ... It would absolutely work in our animation section, but it’s a virtual reality piece.”

“I’ve got my eye on them.”

Chung didn’t have to be nervous about showing "Allumette". Any imperfections are of the kind that are only visible to the person who made it. It's richly realized fantasy world, filled with cobblestones that seem solid, clouds you can walk through and wonder why they don’t feel like San Francisco fog, and a character you ache to understand. You want to see what happens next.

"Allumette" feels handcrafted because, in a sense, it was. Virtual reality experiences are usually created on computers, but Penrose found a new method — working on the piece in virtual reality. That means that engineers and designers are putting on headsets and manipulating the actual environment with controllers to get every single detail right. The tools to do this hadn’t existed before "Allumette." They were never necessary, until Penrose (and others) realized that things would work better if environments could be designed in virtual reality — so they had to develop the tech on the fly. It’s a little like inventing a new kind of paintbrush while finishing a painting.

“The way we’ve done it for decades, it doesn’t translate,” says Chung. “It’s so much faster when you do things natively. You don’t jump out and jump back in to check each part of your work. We’re becoming native VR creators. We’re thinking in VR.”

It’s that experience that makes Chung confident that "Allumette," when completed, won’t be hampered by its length. At 10 minutes, the trailer is at the longer end of the spectrum for virtual reality movies — and it’s only the first third of the final version. Chung talks about the finished product in vague terms, but "Allumette" could ends up clocking in at more than 30 minutes — something that hasn’t been tackled yet by a virtual reality narrative.

What Chung is doing — and he seems to relish the task — is lay out the ground rules for a new art form. It’s a risky business. If "Allumette" is too long, and it gives viewers nausea, or makes their eyes ache, or just becomes impossible to follow, that’s likely a year’s worth of work down the drain. And it’s an invaluable year — other virtual reality creators are puzzling at the same problems Penrose is, and the painstakingly detailed approach means that a nimble studio could figure out keys to success before the perfectionists do. There’s a race going on, but because this is art, no one knows where the finish line is.

Chung has chosen not to make things easy. He’s the son of an opera singer, obsessed with the early days of film, and not looking to pull any punches. “I think ultimately what drives us is pushing the medium forward,” he says. “Audiences can always smell inauthenticity.” At a moment when many virtual reality projects are interested in a documentary experiences that get as close to real life as possible, Chung & co. opt for a claymation-style aesthetic, and jerky stop-motion animation instead of something smoother and less challenging. Chung understands that this is a risk, but it sounds like one he’s happy to make. “It would be a disservice to not try things like that,” he says, “because we don’t have a studio we can make decisions like this.”

When it's finished,"Allumette" will be be a three-chapter-long saga set in a Venice of the clouds, with flying ships powered by perpetual motion machines. It's longer — maybe much longer — than we know audiences will tolerate. It will be about “sacrifice and the love that a mother has for a child, the things that a parent is willing to do for the greater good.”

It will be, if nothing else, the fulfillment of an artistic vision.

“We’re doing this for art’s sake, for story’s sake, not because anyone wants us to,” Chung says.

Art is usually what defines technology, not the other way around. We can list countless films, but no one still marvels at the projector that made them possible. The stage is set for virtual reality’s mainstream release, and it has the potential to become its own medium, but if we look back on it in a few years, the important thing about virtual reality won’t be the refresh rates of the screens or the amount of head-tracking each headset can do, or even the price of each piece of hardware — the tech is going to improve, steadily and probably quickly. What people will remember is the first thing that truly blew them away when they put on a headset. And to find out what’s going to do that, you need artists.

“All the early stuff did was show you that this is a different medium,” says Chung. “Now we need to test those limits.

“It does feel like we’re on the frontier of something.”