ISTANBUL — During annual February 11 parades marking the anniversary of Iran’s 1979 revolution at least one man came dressed as a woman, wearing a blond wig, fake breasts, and lipstick. He was portraying the lone female soldier among U.S. military personnel briefly detained in in the Persian Gulf last month. The event was a typical effort to rile the U.S. But it was also the latest effort to undermine Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s efforts to present a shiny new image of his country ahead of crucial elections on February 26.

Iranians are gearing up for elections to both parliament and the council of clerics, a body that monitors the country’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. This will be Iran’s first election since the implementation of the historic nuclear deal with the U.S. and world powers.

Rouhani, a 67-year-old cleric partly educated in the U.K., has long been a part of the Iranian elite, an establishment figure who knows the ins and outs of the Iranian system. He won the presidency in a surprise 2013 election campaigning as a moderate who would seek to to soften Iran’s domestic and foreign policies. In some ways, he succeeded — signing the deal on Iran’s nuclear program with the U.S. and other world powers, which paved the way for the easing of sanctions.

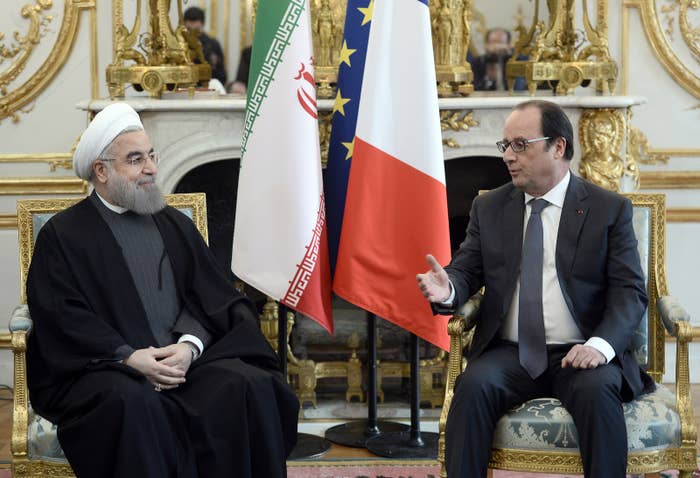

Since then, executives and political leaders from around the world have been rushing to Tehran daily to pursue possible investments and restore ties with a country that boasts the world’s fifth-largest oil reserves. More than 120 foreign business delegations have passed through Tehran over the last 20 months. In selling his country to the world, Rouhani has visited France and Italy, the first such visits by an Iranian president in 16 years.

But improving the economy is proving much harder.

Majid Judeh, a 30-something grocer from Tehran who voted enthusiastically for Rouhani in Iran’s 2013 presidential elections, had hoped the moderate candidate would break the country out of its international isolation and improve a moribund economy reeling from the effects of sanctions over its nuclear program. Speaking by telephone from Iran, he said: “For now nothing has gotten better.”

“The economic situation is going badly,” Judeh said. “But I will likely vote, but only so certain extremists won’t come into parliament.”

Many in Iran and the West discount the significance of Iran’s elections. All Iran’s political players swear fealty to Khamenei and the country’s opaque political system, which vests ultimate power in the hands of high-ranking Shia clerics. But within the circles of elite power, Iran’s reformists, moderates, pragmatic conservatives and hardliners have jostled for power since the world’s first Islamic Republic was founded in 1979, and elections have frequently had important consequences, shifting the country’s domestic and international policies.

On the same day that demonstrators mocked the Americans captured at sea, Rouhani urged voters to come out in high numbers to send a message to those same hardliners.

“Our vote will be 'no' to those who want to turn their back on the law. Our vote will be 'no' to those inclined to disputes and extremism," Rouhani told thousands gathered in central Tehran on Feb. 11. "Today, our goal is to build a prosperous and developed Iran and this cannot be done if the country is isolated … Our people do not deserve old and decrepit railways, aviation, and road fleet. Iranians deserve the best railways, aviation, and roads.”

Rouhani, a Western-educated cleric and jurist who once served as the country’s nuclear negotiator as well as secretary of the powerful Supreme National Security Council, is a wily political insider who has long sought to work within the system to change Iran’s trajectory. But his ability to moderate Iran, turn it into a less ideologically driven place appealing to both middle-class Iranians and foreign investors, is being seriously challenged, potentially limiting his appeal and dampening prospects for the high voter turnout that tends to favor Iran’s moderates and reformists.

He has been challenged every step of the way by powerful hardliners in the judiciary and security forces.

In the months during which the nuclear deal was finalized and implemented, hardliners have sought to illustrate Rouhani’s weakness by cracking down on civil society groups and dissidents. They have increased the number of prisoners executed and locked up dual national and foreign businesspeople on specious security charges, including Iranian-American business consultant Siamak Namazi and Lebanese-American consultant Nazar Zaka. Internationally, hardliners are escalating a high-risk intervention in Syria and have stormed two Saudi diplomatic missions in Iran as well as seized and humiliated the U.S. military personnel who allegedly crossed into Iran’s territorial waters.

Rouhani urged thousands of Iranians to run for office in elections, hoping to pressure his hardline rivals — but an estimated 99% of moderates who applied to run were initially disqualified by the hardline Guardian Council, although about 1,500 of the thousands disqualified were later reinstated. At stake in the elections is control over the 290-seat parliament and 88-member Assembly of Experts, which oversees the office of the Supreme Leader.

Rouhani’s success will likely hinge on whether he is able to convince enough Iranians he has the clout to improve the economy, which remains in bad shape, and the lives of a people that finds its purchasing power diminishing and costs escalating. Unemployment remains high, especially among women and youth. Inflation is down but still rampant. The price of oil, Iran’s economic pillar, is hovering at record lows. Reforms of the expensive state bureaucracy have failed, in large part because hardliners tend to benefit from it.

“The economic situation is more important to people than Rouhani’s travels abroad in informing their election decision or whether to vote,” said Amir Khaleghiyan, a researcher at the Iranian Institute for Social and Cultural Studies, a think tank in Tehran.

“The real situation feels gloomy but there is the other face which is the potential,” said Ramin Rabii, managing director at Turquoise Partners a Tehran-based investment firm. With sanctions lifted it recently teamed up with Charlemagne Capital, a London investment advisory. “Not a single week goes by without having foreign investors here.”

But if Iran seems stable enough to draw European investors, it is in part because the region around it is going up in flames, subsumed by ISIS extremists and civil war. Despite international hopes that Iran would align its policies more closely with the West after the nuclear deal, on almost every front, Iran is moving away.

The number of Iranian or Iranian-backed officers, soldiers, and fighters dying in Syria is skyrocketing. Many Iranians fear it is an investment in blood that will make any withdrawal or moderation of its support for Bashar al-Assad politically unfeasible.

Security apparatuses firmly under the control of hardliners have stepped up their repression of Iran’s civil society, keeping hundreds locked up on political charges. Rouhani’s entreaties to ease pressure on opposition leaders Mir-Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, the reformists who ran against hardline president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in disputed 2009 elections, have come to naught.

Even as Iranian politicians and clergy protested Saudi Arabia’s execution of dissident cleric Nimr al-Nimr, Iran last year executed at least 850 people, more than it had in decades. At least 160 juvenile offenders remain on death row.

Giving Iranians some hope, however small, that the country is heading in the right direction economically might be all it takes to keep the enthusiasm of voters alive and public pressure on the the system high. Elections were the likely reason why Iran’s government so quickly cut a deal with Airbus to buy 114 new aircraft to replace its aging, rotting fleet of civilian planes, a pricey purchase that gives middle-class Iranians a tangible sign of change.

All of this posturing will come to a head soon: Iranian political campaigns tend to be curtailed affairs, lasting just a few days at the most. Voters tend to decide at the very last moment whether to vote and for whom to vote, often influenced by word-of-mouth or, more recently, social media campaigns.

“The voters are waiting to see what the reformists say before they make a final decision,” said Khaleghiyan. “If they can foment a social wave, it will give a big boost to the government.”