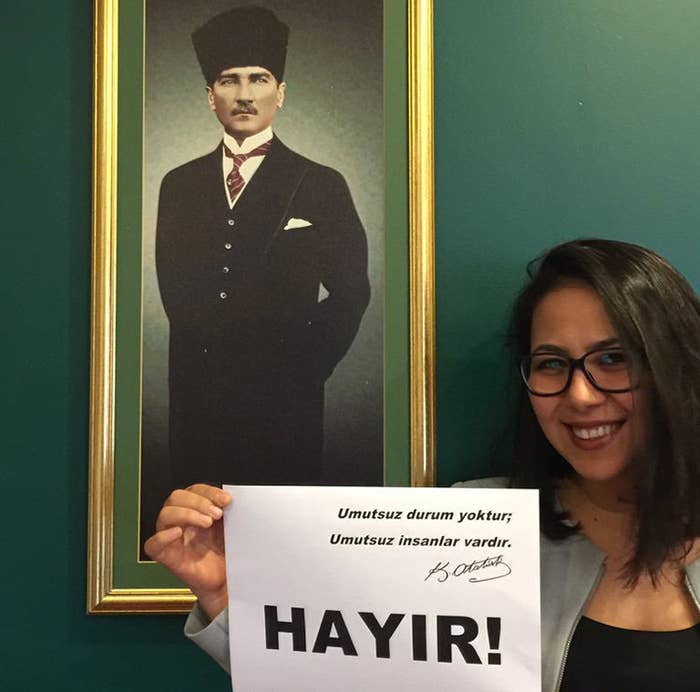

ISTANBUL — Sera Kadigil is in trouble with the law — possibly because she is too eloquent for her own good. In the run-up to a referendum that could radically transform Turkey’s constitution and government, many Turks have taken to the airwaves, or protested in the streets. But, in late January, the 32-year-old lawyer became a social media sensation after she appeared on CNN Turk and made a YouTube video arguing against the planned constitutional amendments, which would further empower Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdogan. If Erdogan gets his way after the vote on April 16, he would gain the power to directly appoint top figures in the judiciary, cabinet members, and his own deputies — without parliamentary approval. Many see it as potentially the biggest political shake-up in Turkey since the republic was founded in 1923.

“Look, I am not saying anything personal about Erdogan,” said Kadigil in a January 25 interview that went viral. “If these changes pass, anyone elected based on these changes can make their son the vice-president. And this son, who has never been elected, can use all these powers given by these changes. If there is anything in this draft to prevent this, tell me and I will apologize.”

A week later, Kadigil, a rising star in Turkey’s main opposition party, the People’s Republican Party, or CHP, was detained during a court visit and hauled in front of police investigators, who grilled her for 15 hours before she was released. Someone had scoured through her social media accounts and filed a complaint about some tweets she had written seven years ago. In one, she had complained about the noise level during the call to prayers — for which she accused of inciting hatred. But Kadigil said she has no doubt that she landed in trouble for speaking out so forcefully against the ambitions of Erdogan and his ruling Justice and Development Party, or AKP.

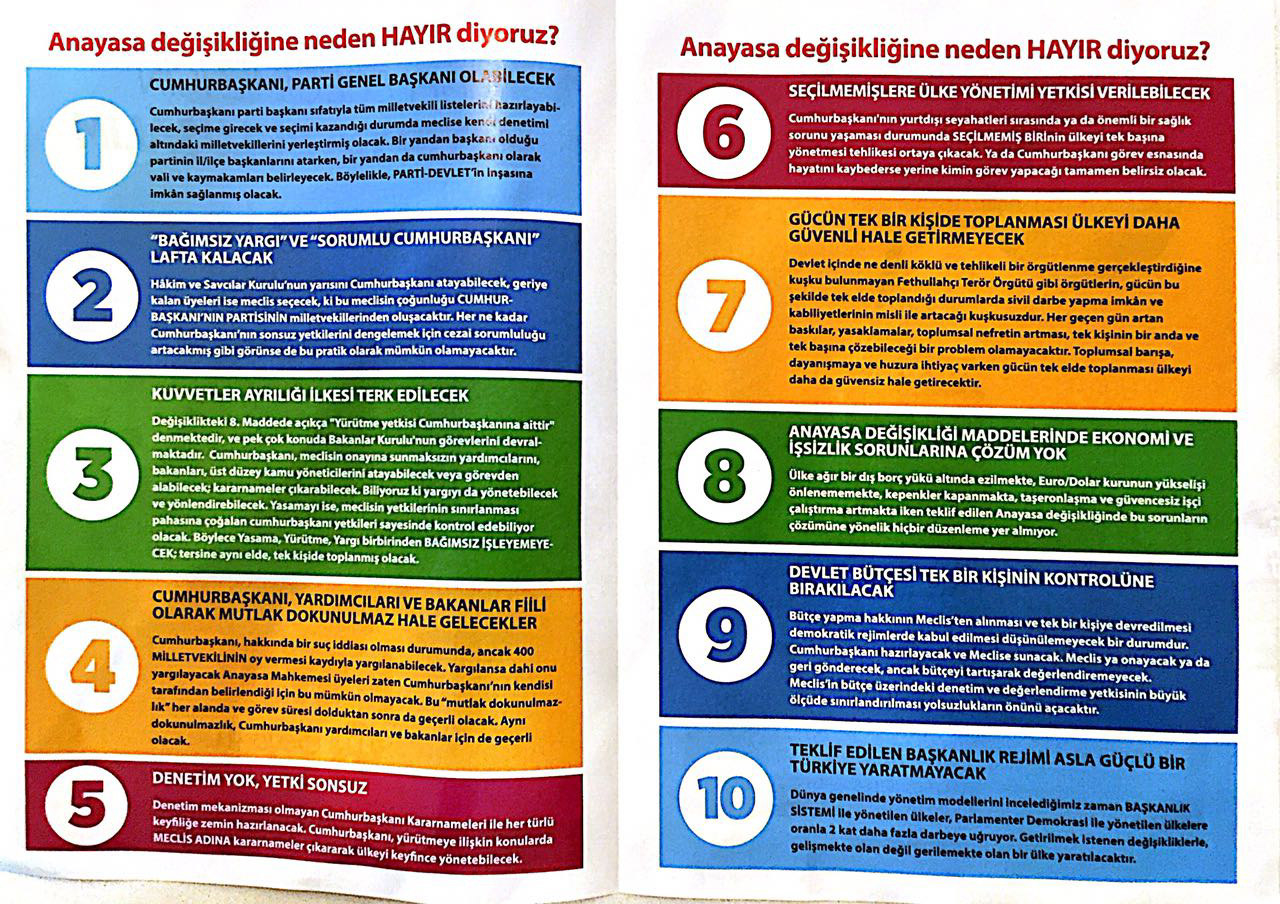

Turkey is deciding on constitutional changes that would transform the government from a parliamentary system where the prime minister is chosen by elected lawmakers to a US- or French-style presidential system where voters directly elect a powerful executive. With polls showing a dead heat between the “No” and “Yes” camps, tensions and tempers have mounted. Last month, Erdogan allies’ attempts to campaign among Turks living in Europe ignited a diplomatic crisis with Germany and the Netherlands. Opponents of the amendments say the changes could lead to authoritarian rule and have accused Erdogan of attempting a power grab.

“I don’t want to have a king and I don’t want to live under a king.”

“People go on TV and don’t say anything because they are afraid,” Kadigil said in an interview with BuzzFeed News. “I just went up there and told the truth. The truth is they are trying to change the democratic system of Turkey, that’s the reality. They’re going to elect a person, and this person is going to choose everything for us. I don’t want to have a king and I don’t want to live under a king.”

Advocates of the proposed changes say the constitutional amendments will strengthen democracy by granting more power to elected officials over bureaucrats and institutions. They note that the proposals have been under consideration by various governments for decades, and that all but one — the rule allowing the president to head his party — would not come into effect until 2019.

“Yes” advocates argue the changes would end what they described as a “juristocracy,” in which Turkish courts have been able to overturn the will of elected officials. “The power of the unelected bureaucracy should be diminished,” said Gonca Bayraktar Durgun, a professor of political science at Ankara University and a “Yes” supporter. “The unelected bureaucracy has to serve the elected one.”

To check the power of the executive, one proposed amendment would lift immunity of the president, who currently can only be prosecuted for treason. The proposed changes, advocates say, are tailored to Turkey’s unique modern history, which has included a series of destabilizing coups. It was in discussions about Turkey that the term “Deep State,” now used worldwide to describe shadowy networks of entrenched elites who pull the levers of power, was first coined. Under the proposed changes, when a crisis erupts, Turks go back to the ballot box.

“Now when there’s a crisis, the military or judiciary intervenes,” Mehmet Ucum, an adviser to Erdogan, told a small group of journalists at an Istanbul roundtable discussion in March. “Under the proposal, if there’s a crisis, it enforces reconciliation, and if there’s no reconciliation, there’s a renewal of elections.”

But critics of the proposed amendments say the changes will further entrench what they call the increasingly authoritarian rule of Erdogan, giving him unprecedented powers over the Turkish state, including naming Cabinet members and top members of the judiciary. They say that the same unelected institutions that the proposed constitution weakens occasionally serve as checks and balances on executive power and protect the rights of political, ethnic, and religious minorities.

“In a polarized society like Turkey, if you give all the power to one side, even if it is elected, you are removing the mechanisms that would protect the rest of society,” said Ilke Toygur, a Turkey specialist at the Elcano Royal Institute, a Madrid think tank.

Beyond the mechanics of the constitutional changes, opponents of the reforms say the political atmosphere surrounding the upcoming vote has been entirely non-conducive to the type of vigorous debate necessary ahead of such dramatic changes. “No” supporters say they have not been granted as large of a platform on broadcast media as the “Yes” camp has. Government officials, including the outspoken mayor of the capital, Ankara, and Prime Minister Binali Yildirim, have smeared “No” voters as supporters of terrorism. A report by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) noted that “supporters of the ‘No’ campaign faced campaign bans, police interventions, and violent scuffles at their events.”

Since a failed July 15 coup attempt, Turkey has been under a state of emergency, with civil liberties restricted, thousands of people imprisoned, and tens of thousands either fired from their jobs or suspended for alleged involvement with the coup plotters or other outlawed organizations. The OSCE report noted the campaign has been marred by polarization and restrictions that have harmed the “No” campaign. Some “No” politicians and activists, including the leader of the Kurdish-rooted People's Democratic Party, have been jailed for previous alleged crimes.

“Constitutional changes in any country require consultation, including opposition ideas as well,” said Toygur. “This was not the case in Turkey. It’s being voted on during a state of emergency.”

“Yes” supporters dismiss concerns about the timing of the vote. Ucum, Erdogan’s adviser, noted that France has been under emergency law for two years and has continued to hold elections. The “Yes” camp denies that the country was dangerously polarized. “No one is arrested for campaigning for ‘No,’” said Ucum. “Turkey is having the most democratic election atmosphere. In order to change something, you don’t wait for a normal time. Political changes happen when they’re mature.”

Supporters of the “Yes” camp say the proposed changes have been misrepresented in the media. Some of them have complained that powerful international players, including Germany, appear to be pushing for a “No” vote. “If Ataturk was alive today,” read a headline in the German tabloid Bild, referring to modern Turkey’s founder, Kemal Ataturk, “he would have voted No.”

While the country’s leftists, liberals, ethnic Kurds, and secularists mostly say they will vote “No” in the referendum, Islamist and traditional-leaning supporters of the AKP say they will vote “Yes.” The nationalists are split, with some supporting the changes and others campaigning against them.

International observers have arrived in the country to keep a tab on the vote. Polls suggest “No” is slightly in the lead. But polls in Turkey have been wrong in the past — almost all of them predicted defeat for Erdogan in the November 2015 general elections, which his party handily won.

In recent weeks, “No” voters have begun putting up banners and plastering walls with stickers and distributing leaflets, arguing that the president will be able to rule by decree. “Turkey will just go backwards and there will be a higher chance of coup d’etats,” warned one pamphlet distributed in central Istanbul. Vans blaring patriotic songs and urging a “No” vote have been wending their way through neighborhoods in an attempt to put people at ease over voting against the proposed changes.

Kadigil said the investigation into her old tweets hasn’t cowed her into silence. She has been speaking at forums and workshops, on the streets and in interviews in a series on new streaming TV channels that sprang up in Turkey as most broadcast networks came under government pressure in recent years.

Kadigil has already had a run-in with the law. She was charged a year ago with insulting the president after using the term “authoritarian Erdogan regime” in a legal brief she submitted while defending her own party in another case brought by Erdogan’s son.

“My parents are afraid for me but fully supportive,” Kadigil said. “All my friends are worried about me. They’re actually worried they will kill me. Actually, all the pressure is a way to stop people from voting ‘No.’ We cannot stop right now. If a donkey is already dead, he’s not afraid of the wolf anymore. I don’t have the luxury to be afraid.”

• Burcu Karakas contributed reporting to this story