Ọṣun was used to being looked at. In awe, lasciviously, curiously. Instinctively, she knew when eyes were drawing across her, trying to figure out what they could from her figure. Chin slightly raised, arms and legs lean and athletic, and wide hips that swayed and exuded a femininity so innate it refused to be contained; to some it was a call they felt they had to respond to, to others, a declarative statement of power, something to fear, revere.

As a competitive swimmer at Ifá Academy, she had an intrinsic allure that followed her as she flew into the air before diving into the pool. Prizewinning, majestic, her limbs flew through chemicalized water as if it were the sea and she were the current itself. The energy itself. The gravity from the moon itself. She transformed the pool into a sun-dappled lake. Though she moved with incisive swiftness, she made her preternatural ability look breezy. It was casual magnificence. She pushed and pulled as if she were conjuring power from the water. Those who watched often mused that it seemed as if the water only existed to propel her.

Ọṣun was accustomed to being a spectacle, people observing her in wonder, trying to surmise what they could from what they saw. Which was why she hid as much as she could, and kept as much of herself to herself as she could. Swimming was her sanctuary, it was just a shame that it necessitated an audience. During swim meets she paid no attention to the roar from the bleachers or the superfluous commands from her coach (the coach was decorative, a symbol that represented the school’s power over Ọṣun’s triumphs, as if Ọṣun hadn’t made a dry basin bloom into a lake by dancing in it at 3 years old).

In those swim meets, she focused on the sound of the water smacking against her skin like a hand against the taut hide of a talking drum. Her swimming became a dance to a rhythm she was creating with the water. With each hip switch a hand sliced through the water till she was no longer just a body among bodies within a false aquatic body, tiled and sterile. No, she was the body, the only body, vibrant and heavy breathing. By the time the music stopped, she was over the finish line, alone. All they saw was an excellent athlete; only she knew that she was a dancer.

Ọṣun was used to being looked at and ignoring it. Most people would say that, when they looked in the water, they saw themselves, but what they really saw was their reflection, light bounced back. A reflection was just the water rejecting an unwelcome intrusion. Water was generous, but mostly it wanted to be left alone. Come in if you want, drink if you want, but don’t peer in without engaging. However, when Ọṣun’s gaze met the waves, she really saw herself. Her hair was soft, dark, and roiling, with thick coils swelling around her face like a towering tide. Her face held deep, striking eyes that tilted inward slightly, as if too heavy to stay steady. They carried too much, they carried the whole universe, and were fathomless like the ocean. Her skin was as deep and smooth as a vast lake, its sparkling surface harboring an unfathomable depth beneath, a whole world beneath. The water beckoned her in as kin. She was a highborn: unknowable, untouchable, and unable to be contained. One could enjoy but never possess. Experience but not capture.

She was a highborn: unknowable, untouchable, and unable to be contained. One could enjoy but never possess.

But Ọṣun felt captured by the gaze on her now. It was all-consuming and sank through her skin. She detected the most tucked away parts of her stirring, being drawn to the surface. She didn’t know the source of it but she felt it. She was sitting on a large hide-skin mat at the academy’s celebration of the iteration of the Ojude Oba Festival with a loose smattering of people who liked to call themselves her friends, drinking palm wine from coconut cups, her lips glistening with fried sweet-bread oil, observing the festivities. The air swelled with laughter, music, the scent of fried plantain, roasted meat, and spiced rice.

Ebony horses in colorful leather swayed, their manes entwined with red, yellow, and green ribbons, and were led into the parade by the academy’s jockeys, who matched their steeds’ majesty with brightly dyed, flowing agbadas and fila. They directed their horses through elaborate routines with elegance and expertise, despite their heavy, cumbersome outfits. Talking drums were having loud conversations, orchestrated by the Tellers, the elite drumming league of the academy, who learned and recorded history through music. They spread news, provided entertainment, and bantered through verse. Their chests were bare, gleaming, and their arms were tense as they slapped and tapped the hide-skin with both palm and stick, alternating in notes and somehow gleaning harmony from each strike.

Students were dancing to the tale of their town’s origin, to love stories told through cadence, laughing, waists rotating, and feet blowing up red dust as they pounded. They celebrated the gods and goddesses who comprised their alumni, those who had ascended to the highest of heights. All throughout the merriment, Ọṣun felt that look searing across her skin, making her heartbeat quicken so it syncopated with the sound of the drums. Part of the reason Ọṣun didn’t know who was looking at her was practicality. She couldn’t turn to see. Her neck was secured under the firm, sinewy arm of Ṣàngó, student chief elect of Ifá Academy, captain sportsplayer (of all the sports), captain girlplayer (of all the girls), with a charm as ferocious as his temper and gray eyes that lightened and darkened according to his mood. It was a known fact within the academy and within the county that Ọṣun was the only one who could calm him when he thundered over some perceived disrespect or when someone dared to question his innate authority.

Ọṣun was the only person who saw Ṣàngó’s eyes slide from slate to silver close up. She would walk into the midst of a brewing fight, the crowd parting way for her, and lay a hand across his tense jaw and look up at him. Murderous fire would turn to amorous flame, angry gusts of air into soft billowing breath. She would take his hand and lead him out of his own chaos. All of Ṣàngó’s girls didn’t matter, because Ọṣun knew she was all of them put together, and more. They were just iterations of her, splintered into lesser forms. There was a smiley girl who lived a few compounds away from Ṣàngó whom he liked to spend time with. Ọṣun didn’t mind this. Ọṣun knew that, when she smiled — rare, but it happened — it was as bright and as intense as the sun at noon. It could intoxicate those around her into such euphoria that, when the high ebbed, they felt like they were plummeting into the depth of all the despairs of the world, compounded. Ọṣun didn’t know what would happen if she laughed. She never did.

Then there was the girl whom Ọṣun had constellation observation class with. Ṣàngó often visited her after festivities, loosened with palm wine. She was a girl who acted as if she hadn’t drunk since the moment she was born, and whose thirst could only be satiated by Ṣàngó’s sweat on her tongue. Ọṣun didn’t mind that either. Ọṣun knew that, when they were together, Ṣàngó drowned in her, died and came back to life in her, and that when their hips rolled together, it was stormy waves: almighty, thrilling, terrifying. She knew she tasted like honey and liquor and that she left him both satiated and insatiable, tipsy, and all at her whim. Ọṣun knew that she was all Ṣàngó ever wanted and more. She knew it was the More that terrified him. The surplus taunted him. She knew that sometimes having everything you desire can make you question your own worthiness. Ṣàngó didn’t like the taste of his own insecurities. He never liked to wonder whether he was Enough to match her Too Much, so he had to seek balance with diluted derivations of her. She was fine with all of this until the week before, six days before the Ojude Oba Festival, at her sister Yemọja’s Earth Journey celebration.

The party was thrown at their compound, and Ọṣun had ventured out into the surrounding forest for a break. She admired her sister, who’d ascended from the school a year ago, but she often found her presence overbearing. When Yemọja laughed, it sounded like waves crashing against the shore, and often Ọṣun felt like the craggy cliff walls the waves cuffed against and eroded. The two sisters had the same face poured into different forms. Ọṣun felt her sister was a more sophisticated version of her. Yemọja was taller and lither, whereas Ọṣun was shorter and curvier, defying the prototypical mold for athleticism. Yemọja was an expert sailor, often leading teams of 40 or 50 vessels on voyages of exploration. She had mastered the waters so that she needn’t ever submerge. Ọṣun felt weak for needing to feel the ebbs against her skin.

Yemọja highlighted what Ọṣun lacked, and though Ọṣun loved her sister and her sister loved her back, she couldn’t help but feel lesser around her. People hung on to Yemọja’s every word and Ọṣun watched them do it, saw them use those words to hoist themselves up spiritually, charmed and bolstered by Yemọja’s presence. Seeing this, Ọṣun had tried to strike up conversation at that party, in a valiant attempt to emulate her sister’s charisma, but she found that, when she spoke to people, they watched intently as her lips moved, their eyes following how her mouth shaped words, rather than listening.

So Ọṣun left the teeming party and went for a walk through the forest, aiming for the river, a place where she felt peace. It was a surprise when, through the thicket by the riverbed, she saw the broad, muscular shoulder of Ṣàngó, who, a mere 30 minutes earlier, had wrapped a thick arm around Ọṣun’s waist, pulled her to him, and whispered that she was his love and that it pained him that he had to socialize when all he wanted was to be with her, but that he needed to collect more ale from the seller with a few of his men. Now that arm was around someone else. Through branches that seemed to cower in embarrassment, Ọṣun saw that Ṣàngó’s neck was bent as he whispered something into that Someone Else’s ear before kissing it.

Sometimes, when you are hungry enough, you can will the ghost-taste of sweet-bread in your mouth. It will make you hungrier, though, and emptier.

He then said, louder, “Ọṣun doesn’t like to dance. I miss dancing. Dance with me.”

He moved slightly to reveal Ọba: Ṣàngó’s former lover-friend, pre-Ọṣun, her baby-round eyes soft and stupid, small pretty flower mouth, waist moving with smooth respectful reverence as Ṣàngó called to her with his hips, jutting in response to the beat of the faraway drums. The way her waist moved was polite and coy, technically rhythmic but with no fire of its own. Even in dancing, she was bowing for Ṣàngó. Ọṣun rolled her eyes. This, Ọṣun hadn’t been fine with. Ọba was meek and irritatingly sweet, a sweetness that Ọṣun found cloying. Even after Ọṣun had successfully captured Ṣàngó’s attention, Ọba had been kind to Ọṣun, insisting she held no ill feeling, that all she ever wished was for Ṣàngó to be happy. Ọṣun had found this exceedingly pathetic and would have had more respect for the girl if she had sworn a vendetta, if she had told her to her face — like a warrior — that she would not be letting him go.

However, Ọba’s involvement was not what struck Ọṣun so hard in her chest that she almost stumbled back. It was Ṣàngó’s words. It was a lie. Ọṣun loved to dance. She and Yemọja danced by the seashore every night at sunset, drumbeats rising from the ocean for them, their laughter melding with the roar of the tide. Ọṣun danced every time she was in the water. She thought that Ṣàngó, at least, saw that. Through everything, the one thing that kept her tethered to Ṣàngó was that he saw her. They saw each other. Sometimes, not often, but sometimes, when she was with Ṣàngó, she felt close to how she felt when she was in the water. She realized now that this was an illusion. Sometimes, when you are hungry enough, you can will the ghost-taste of sweet-bread in your mouth. It will make you hungrier, though, and emptier. And sometimes you won’t know how truly bereft of food you are until it’s too late.

After a few moments, Ọba saw Ọṣun through the branches and froze. Ṣàngó followed Ọba’s gaze, saw Ọṣun too, his eyes flashing in alarm, a bolt across his face. Ọṣun observed his eyes slide from silver to slate. He stepped forward, Ọṣun raised a hand. Ọba looked sorry for Ọṣun, which made Ọṣun feel sick to her stomach. So Ọṣun smiled, wide and beautiful, dazzling and terrible. It made Ṣàngó call on the rain clouds for anchor, and the sky turned gray. It made Ọba feel like she was submerged in the river behind her, unable to breathe, to see, to speak. Then Ọṣun turned around and returned to the party as if nothing had happened.

After that day, Ọba found that the ear that Ṣàngó had whispered in felt like water had plugged it. Try as she might, nothing would pour out. Herbalists couldn’t fix it, priests feared it. It forever felt as if she were half submerged in the river. From that day on, Ṣàngó was too terrified to speak to Ọba ever again and didn’t dare visit his other girls. For reasons Ọṣun could not confess to anyone, not even herself, she stayed. Ṣàngó still never asked Ọṣun to dance.

He was talking to his boys now, palm wine sloshing out of his cup. Ọṣun rolled her eyes. Ṣàngó loved an audience, adored holding court, regaling them all with stories from sports tournaments, from the places he visited and sought to conquer when he ascended the academy. His people laughed on cue, a chorus in a call-and-response tale, unable to display anything but sycophantic joy as Ṣàngó told of how, once, a market man refused to sell a lion-skin cape to him. The man had told him the cape was for men with honor, and that he hadn’t seen enough in Ṣàngó to sell it to him.

“I told him I would rule over him one day. Old fool said that he knew. He said that he hoped that I would accrue enough honor for the lion skin, that my back would become broad enough for it. Can you imagine? A whole me. A whole me who can carry an ox on his back? Two oxen! I thought he must have surely been joking.” Ṣàngó spat into the earth as his eyes melted into something darker than slate at the memory. “So I laughed in his face.”

With Ṣàngó’s angry laughter came thunder, and with thunder came lightning.

“The only problem was that now the lion skin was stained with ash. Dyed with idiot.”

His court roared with jest. Ọṣun felt ill.

She shrugged Ṣàngó’s arm off her neck, feigning that she was readjusting the multicolored beads that hung around her throat. The feeling of being watched grew more intense. She turned around, and through the heated dancing bodies, she saw a tall, lithe, muscular figure, leaning against a tree. His arms looked like branches twined to make a trunk, and so it almost seemed as if he were mocking the fever tree’s strength. He was eating a rose apple, white teeth sinking into membrane and then flesh, playful eyes never leaving Ọṣun’s. His left ear glinted with a silver crescent cuffed into his lobe and it matched the flash in his eyes. It was different from the light she saw in Ṣàngó’s eyes, which was entirely indicative of himself, his whims. Ṣàngó’s eyes flashed lightning when he was in the mood to drown in her, but he never asked her if he ever made her catch fire. This man’s eyes were calling her, pressing through her. He was seeing into her and he wasn’t bowing. He had three striking scars across his muscular chest, on the left side, welts she immediately wanted to run her fingers across. He smiled at her as if he knew.

She turned back around, alarmed. She pinched her sister next to her and drew her away from the conversation she was engaged in. Yemọja was Ọṣun’s closest friend, in that she was her only friend, bound by blood and bonded through water.

“Turn around slowly, like you’re looking for someone. Do you know who the tall new boy is?”

Ọṣun said “boy” to calm herself, to allow herself to feel some semblance of control over this man whose gaze was making carefully compacted parts of her stretch and bloom into their fullness.

Yemọja blinked twice, thrice, startled that Ọṣun was talking to her casually about things that regular sisters talked about casually. Yemọja’s baby sister was extraordinarily beautiful, and extraordinarily, beautifully strange. Once, when they were on the benches in the school field, watching Ṣàngó and his boys defeat another county, Ọṣun’s eyes had glazed over and she’d said, “Did you know that thunderstorms don’t always produce rain? It’s a shame, because the rivers hear the thunder and see the lightning and expect to be filled up, only to end up disappointed. Dry thunderstorms are just show-offs. Scaring birds and burning trees while the river pants. Forgetting that the river helps feed the clouds that thunderstorms are created from.” Her eyes never left the sports field as she spoke. Soon after, Ṣàngó scored the winning goal.

Yemọja rarely knew what Ọṣun was talking about. She often nodded and smiled when Ọṣun uttered things like this, knowing that anything she replied would only ever make Ọṣun’s eyes shadow in impatience, would cause her to retreat quickly again, when her cerebral soulfulness wasn’t matched. Yemọja was of the ocean as Ọṣun was of the river, but Yemọja was earthy, practical, tethered to the things of this world, tied to the unanointed peoples, so she could relate to them, mother them. Her younger sister had the freedom to stay connected to the heavens, to allow her psyche to dwell outside this realm. Yemọja was the root and Ọṣun was the blossom, forever reaching for the sky.

And so Yemọja pretended to understand what Ọṣun was saying and Ọṣun pretended that she was understood. It was a sweet kindness they shared that benefited them both. But Yemọja understood Ọṣun clearly now and was pleased. Ọṣun needed more than Ṣàngó. Ṣàngó would rather make himself feel bigger with women less powerful than Ọṣun instead of elevating himself. Yemọja did as she was told — turned around casually — and when she turned back to Ọṣun, her smile was gleeful.

“Ah. That’s Erinlẹ. He is joining the academy next season. He won the country-wide competition for a spot and was invited to this festival as an early introduction.” They had shifted away from Ṣàngó and his boys — not that it mattered. They wouldn’t have been able to hear the sisters speaking over the sound of their own voices and the giggling girls surrounding them anyway.

Ọṣun nodded and sipped at her palm wine. Yemọja smiled wider. Ọṣun barely drank. “What won him a place here?” Their academy was selective, a training campus for the gifted. One was either born into it, being of celestial heritage, high blood (Ọṣun, Yemọja, and Ṣàngó), while others were scouted for their particular skill, sourced through tales of power and often mysticism throughout the counties. They were known as the earthborn; of the rooted realm.

“Hunting, my heart,” Yemọja said, allowing herself the indulgence of using an intimate term of endearment. To Yemọja’s pleasure, Ọṣun didn’t flinch.

Ọṣun nodded and poured more wine into both their bronze cups from a gourd.

“So he’s an earthborn.”

Yemọja shrugged. “Aburo mi, it means nothing. We are all equal here. Those who are supposedly highborn often act like they were born beneath ground.” Yemọja sidled her eyes to where Ṣàngó was sat, tipsily jeering, and Ọṣun bit into her smile.

She found she liked the feeling of being enjoyed for what she freely gave.

Yemọja continued, shuffling closer to Ọṣun, so their shoulders were touching. If strangers saw them, they might have presumed that they’d always been this way, companions, confidantes, sisters by blood and friends by choice, that they sat between each other’s knees and braided each other’s hair while gossiping as ritual.

“He is a master bowman. Farmer too. It’s said he can bring crops to life with a touch. Good with his hands.” She shot a knowing, playful look at Ọṣun, and to Yemọja’s surprise, Ọṣun allowed herself a tiny fraction of a smile. It made Yemọja feel like she’d won something and she felt bolstered to continue. “It’s said that the scars on his chest are from when he fought a lion. They say the lion wanted to eat his heart for his strength.”

Ọṣun took a sip of her wine. “Or the lion wanted to eat his heart because it was a lion.”

To Ọṣun’s surprise, Yemọja released her ocean roar of a laugh; it bubbled out of her. People didn’t often laugh around her. Did she say something funny? She wasn’t aware, but she found she liked the feeling of being enjoyed for what she freely gave.

“Well, Erinlẹ won. Clearly. As you can see.” Ọṣun looked up and saw that Erinlẹ was now in front of her, in the middle of the courtyard, a talking drum leaning against his taut torso and his arm, joining in with the music. Her eyes dropped and she realized that, around his waist, was a wide strip of tanned sandy hide over his deep rust-hued woven cloth. Lion skin.

Erinlẹ was smiling as he made the talking drum sing, joining in easily with the Tellers. The Tellers were notoriously unwelcoming to newcomers, an elite band of expert musicians who came from expert musicians. But here they were, folding him in, and Erinlẹ not only matched them, he made them better. Now that he was closer, she could examine him more. His skin was a deep reddish brown, the exact tone of the earth by the riverbed at her favorite place to swim.

“May I speak with you?”

She heard a low, cool voice that she somehow knew belonged to Erinlẹ, and yet his mouth didn’t open. His eyes were trained on her intently. She held still. Ọṣun was very sure that he had spoken without speaking.

“It seems that you’ve already allowed yourself that honor,” Ọṣun dared to think, playing with the notion that he might hear her. From the broadening of his smile and the light in his eyes, it was clear that he had.

“No. I was just knocking. Testing. Seeing. We both know that, if you didn’t want me to speak with you, I wouldn’t be here.”

Ọṣun could see now that time had stopped — or at least it had been suspended. The red earth and deep green of the forest melted into a thick smog. Ṣàngó’s laughter sounded as if it had been submerged in water, and her sister’s warmth had ebbed away. Everybody was a blur. The festival was occurring in slow motion, as if it were a dream. She found that she was now standing opposite Erinlẹ, inches away from him, close enough to reach out and touch the ridges of his scars if she were so inclined.

Ọṣun forced her eyes away from his chest and directed them plainly into his. “Why would I want you in my mind? I don’t know you.”

Erinlẹ’s gaze made Ọṣun’s blood blaze beneath her skin.

“I don’t know you, but you’ve been in my mind. I guess just not in the same way. Not in this literal sense.”

Ọṣun tried to swallow her curiosity (she wasn’t used to the taste, as she rarely found what men said to be interesting), but it rose back up to push a question from her lips. “In which sense, then?”

“In the sense of a young man wondering about the woman who would one day hold his heart.”

Ọṣun found it in her to roll her eyes, to conjure the semblance of dismissal, despite the fact that every cell in her body thrummed with the knowledge that this man wasn’t speaking with regular flat flattery — this was not an attraction tethered to how her being in his possession would make him feel. He spoke plainly of her power over him, and he didn’t cower, didn’t puff up his chest to overcompensate.

“And how do you know that’s me?”

Erinlẹ shrugged in a matter-of-fact manner. “How do crows know when an earthquake is about to happen?”

Ọṣun raised a brow. “So, you sensed your destruction?”

Erinle laughed, eyes glinting. “I sensed my world about to shift.”

Ọṣun’s heartbeat was steady at all times, but now it was frantic, hectic, at odds with the stillness surrounding them.

Ọṣun cleared her already clear throat. “So, is this your power? Summoning people out of the world and meeting them in their own?”

Erinlẹ stepped closer to her. “It’s your power. You called me here. I am earthborn — my gifts were blessed to me. But I read that sometimes this can happen when two energies find something in one another that compels them to each other.”

“And what about you should compel me?” Aside from his smile, his warmth, and the fact that she felt herself unfurling around him. “I don’t need anybody.”

People sought to touch without acknowledging her desire to be caressed, to consume without realizing her craving to just be held.

Erinlẹ laughed and nodded. “I am aware. It’s not about need, but desire.”

Ọṣun swallowed. “What I desire is to know why a strange boy was staring at me from afar. I want to know what made him lose himself to be so bold as to look at Ṣàngó’s beloved so openly.”

Erinlẹ shrugged. “I didn’t lose myself, I found myself. Whether or not you are Ṣàngó’s beloved is of no consequence to me. You are not his possession. It’s a lie he believes to make himself feel better about himself. I wasn’t looking at Ṣàngó’s beloved, I was looking at you.”

Ọṣun held still for a moment and regarded him, feeling something swell within her. Something visceral, that pushed her to carry through with her inclination to allow a finger to sweep against the lines across his skin, transgressing the lines she drew for herself, rules that disallowed anyone to see her innermost desires. As she touched the scars left by a jealous beast, the long-healed and -sealed gashes shimmered beneath her touch, glowing bright and amber.

Erinlẹ watched her, his eyes veered from playful to serious as he reached to tilt her chin so that her gaze met his, unabashedly, nakedly.

“What do you want, Ọṣun?”

Ọṣun opened her mouth but found that her words got stuck. Want. Ọṣun hadn’t wanted in a long time. She was obliged to hone her gifts. Obliged to represent the academy. In many ways, she felt obliged to be with Ṣàngó, representing the highest of the highborn, but Ọṣun couldn’t remember the last time someone asked her what she actually wanted. People sought to touch without acknowledging her desire to be caressed, to consume without realizing her craving to just be held. They looked but never saw.

Erinlẹ looked at her intently, as if he was seeing her More. He smiled and it rippled sunlight through her.

“Ọṣun, oh, Ọṣun . . .”

Ọṣun froze. Was he singing? His mouth was moving, and he seemed to be starting a chorus with her name, beating the drum, looking her in the eye. The world rushed back into sharp focus, the sound flooding back into Ọṣun’s ears with almost painful clarity, just in time for her to hear Ṣàngó’s conversation draw to a complete halt.

“Did he just say your name?” Ṣàngó’s voice was incredulous.

“Yes. He did,” Yemọja responded smugly, on the opposite side of Ọṣun, as Ọṣun forced herself to quickly acclimatize to the world around her. Her conversation with Erinlẹ hadn’t been more than a split second in the temporal sphere, but her whole body felt more alive than it ever had, everything around her seemed more vivid, clearer. Ọṣun felt more of herself brought forth to the rooted realm. She felt more of herself in general.

Erinlẹ’s singing was a bold move. Nobody sang but the Tellers. To sing you had to be elected by them or appeal to them in front of an audience. Nobody sang directly to others unless they were friends teasing each other, friends congratulating each other, or if they were initiating courtship. It was more than being able to hold a note: One had to be able to draw song on the spot, it could not be precomposed. It’s how you knew it was from the heart, and it had to be from the heart. Ṣàngó had never sung to her. Ṣàngó had never sung to anyone. He prided himself on never having to.

Ọṣun could hear Ṣàngó beginning to thunder next to her and she turned to him, allowed her eyes to be as fathomless as possible. “Be still.”

Ṣàngó’s jaw tightened, but she felt the rolling of his thunder subside immediately. Whether he liked it or not, Ọṣun had his heart in her palm. She scared him. The whole festival had now turned to pay attention to the spectacle, Erinlẹ’s small hooked cane beating an intricate, delicate tune that seemed to conjure up the image of Ọṣun. It rolled like the gentle ebbs of a river, it sounded sweet and fierce and plush. Erinlẹ was walking slowly up to her, drum slung across his torso, gripped under his arm as tightly as his eyes gripped on to hers.

“Ọṣun, may I borrow you,

I will kill a thousand lions for your dowry,

Scale mountains to pluck the stars for your wedding jewels,

Slap the clouds to make them cry so your rivers will always overflow.”

Ọṣun laughed. That was what she wanted to do. She wanted to laugh. To allow all the parts of her she tucked away to flow freely. To escape the trappings of expectation. To be. People gawked. No one had ever heard her laugh before. Ṣàngó had never heard her laugh before. It sounded like birdsong and the laps of a river. Erinlẹ was beckoning her, looking directly into her eyes. The timbre of his voice made her blood thrum and the hairs on her skin stand up. Ọṣun suddenly felt lifted, as if she were swimming. The drumbeats felt like waves crashing against her skin, beckoning her as kin.

“Stand tall, my queen. I would give you the universe but how

Can I gift you to you? So I will give you my heart, strong and true,

I cannot conjure thunder, but

I will plant a forest for you, sow flowers that bloom

In your presence, fruit that tastes like your essence.”

It was supposed to be bawdy — these songs usually were. However, the way he sang caused electrical currents to course through Ọṣun’s body in a different way from when she was with Ṣàngó. These currents depended on her; it was as if his energy caught fire through contact with her. She had to agree to it for it to blaze.

Erinlẹ was now in front of her.

“Ọṣun, oh, Ọṣun,

My beat is calling your waist,

Won’t you answer?

Won’t you answer?

You look like a woman who loves to dance.”

Ọṣun got up, legs unfolding easily beneath her as the clouds above rolled. She paid no attention to Ṣàngó. She followed Erinlẹ to the middle of the courtyard and allowed her hips to switch with the beat, her arms to sway through the air, laughing as she did so, as Erinlẹ bent low with his drum and dipped and rose as she moved, responding when she called with her waist. There was thunder, but Erinlẹ’s drum rose above it, interlaced with Ọṣun’s laugh. There was lightning, but Ọṣun’s smile outshone it. Ọṣun was used to being looked at, but, from this moment, she would become used to being seen. ●

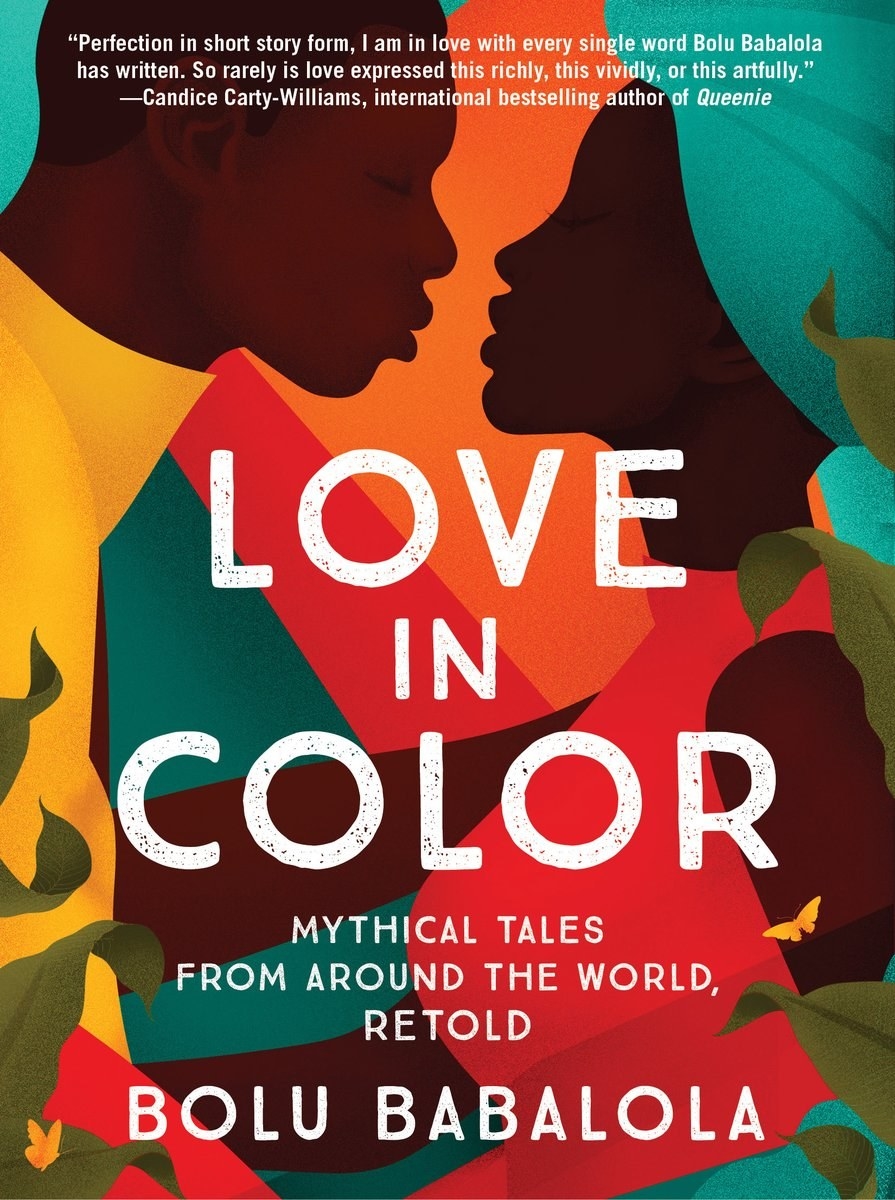

From Love in Color: Mythical Tales from Around the World, Retold by Bolu Babalola. Copyright © 2020 by Bolu Babalola. Reprinted courtesy of William Morrow, a division of HarperCollins Publishers.

Bolu Babalola is a British-Nigerian journalist, writer, and lover of love. In 2016, she was shortlisted in 4th Estate’s B4ME competition for her short story “Netflix & Chill,” a hilarious tale of teen romance. While writing scripts for TV and film, she also works as a content creator, where she calls herself a “romcomoisseur.” This is her debut anthology.