Here are the rules.

If you naturally possess freckles, they must be showing. Depending on the overall mood of the shoot, eyes may be vamp-narrow, but ingenue-wide is preferred. There must be skin — acres of it — showing, but that must remain innocent, somehow. Think of a maiden taking a midday dip in a stream: naked, sure, but never knowingly flaunting anything.

Lips must be nude (or made to appear nude, in what countless YouTube makeup artists call “you, but better”). Hair must have the quality of slight dishevelment, whatever that means for the individual star. It could be wisps escaping at the temple, artfully arranged — the fuzzier the better; these are the perfect conditions to let static electricity thrive. Or it might mean just letting all that hair cascade down in an approximation of youthful carelessness.

As for makeup, if the star will not go fully nude (there are rare brave souls who sometimes do this) the touch must be light: no aging heavy black liner, eyeshadow must be complementary and light, brows must be left faux-unruly, and you can forget a contour stick. Simple, unfussy fabrics (wool and cotton over anything synthetic) complete the look. The aim is to appear unvarnished, pure, youthful but not childish. It takes work, as the long credits of these shoots always reveal, but it must seem largely effortless. Effortlessness is, after all, the greatest commodity a woman can own.

It is the look sported by Ariana Grande on the cover of British Vogue last month. Xtina did it for Paper recently. Kerry Washington did a version of it for Allure back in November 2014, as did supermodel Gisele Bündchen for Vogue Italia earlier this year (PopSugar called it “history-making”).

Welcome to the “unmade” magazine cover, a subtle rebuke to the prevailing makeup aesthetic of our time.

In recent years, a powerful dialect was added to the language of beauty and cosmetics. The full face of makeup has enjoyed a renaissance. Maquillage (saying it in French glamorizes mundanity like nothing else) as an everyday hobby, as an extension of personality, as a sacred ritual of multiple steps (that has grown far from the “cleanse, tone, moisturise” of my youth) has become popular enough to grow its own field of thinkpieces. We are in an unsubtle age, and the prevailing makeup trend eloquently mirrors this. This aesthetic is unflinching in telling you just how much effort went into producing it. More is more, as Rihanna memorably put it in her 10-minute makeup tutorial video for Vogue. The overt effort is political and self-aware, and those elements are a huge part of its charm.

View this video on YouTube

Rihanna makeup tutorial.

We have watched, in real time, the rise of the super-made-up female face in which proponents carve shadows and bridges into — and sheer cliffs out of — their faces. No one who does makeup even casually is unaware of what it means to highlight, to contour, to bake and set. There are tutorials for the “Instagram baddie” makeup look, entire YouTube channels dedicated to telling the very specific story of beauty in the late 2010s. There is a set of people (who are not in the business of old-fashioned entertainment) for whom false eyelashes are somehow a necessity. Microblading and nanoblading are on the up. “Who wants to be low maintenance anyway?” asks a wall of gold text on a Soho shopfront. “And since when is owning a single lightly tinted ChapStick a good thing?” It’s advertising for Il Makiage, a makeup brand whose tagline is “makeup for maximalists.”

The idea of makeup as armor, the mask that must be tacked on in order to pass muster in public — in order to be adored, essentially — is not new. There are entire schools of thought and study dedicated to the place of makeup in human life and civilization. Makeup has (staying) power.

To be successful on a pandemic scale, viruses need to have two things: a high mortality rate and the ability to spread very easily. It happens less often than people think. Similarly, makeup trends and products — less obviously occupied with wiping us out — need to mutate to survive and to stay relevant. They are always seeking a way to marry super virality with super accessibility. And they succeed very often. Two very different approaches to makeup have been in effect for the last few years: the maximum drama and the no-fuss minimal. In the red corner, Kim Kardashian West, kontoured to the gods, at a high-profile event. In the blue, Alicia Keys in black and white on the cover of her album. Well, sort of.

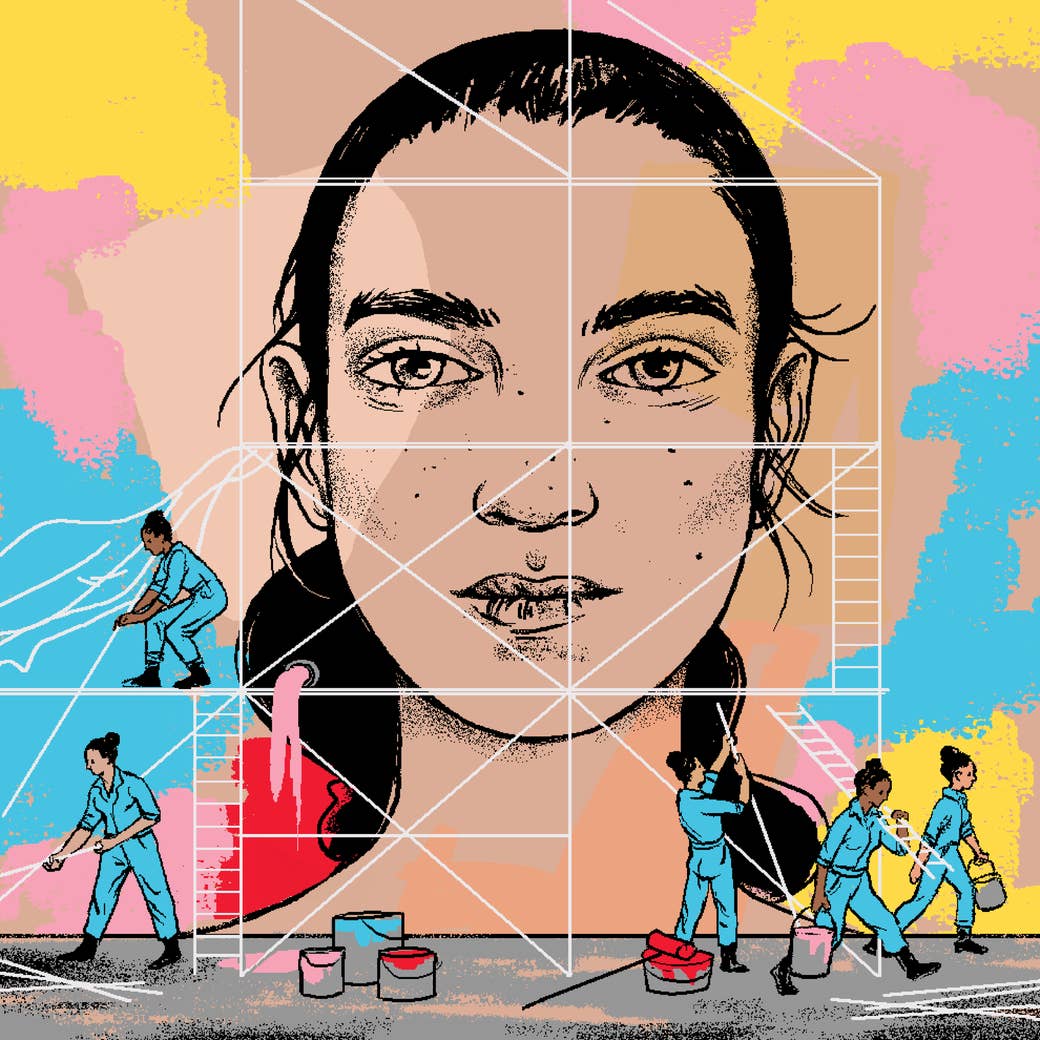

At a recent live show recording of the Unladylike podcast, New Yorker writer Jia Tolentino noted how the labor of makeup only grows over time. Once a trend has picked up the necessary speed and replicated itself across the globe, it might fall out of fashion but it never really goes away. Instead, it is folded into the existing framework of how we see beauty. The palette, once opened, stays widened; Pandora's box is already open, even though we have some cures. Makeup is work. And so many women are consistently toiling, and wearing their labor on their faces. The result has the appearance of a kind of assembly-line, cookie-cutter perfection — all the right parts in the right places — and there is nothing “natural-looking” about it.

It is worth noting that the toning down of makeup comes at a time when we are also turning up on “skin care.” What is being sold with the dizzying array of skin care lines is a version of time travel wrapped up in the idea of a new makeup freedom. Where we once focused on makeup’s magical ability to perfect the imperfect, the onus is shifting: Why cover up when you could make the canvas itself flawless? Enter Glossier, Deciem, Milk, Sunday Riley, and other brands, purporting to get your face where it needs to be, whether you are looking to minimize your (already tiny) pores, brighten your (not that dull) skin, or overwhelm free radicals with any number of miracle serums. Think of Glossier’s branding: “Skincare is essential, makeup is a choice. (Make good choices.)” This is a new kind of perfectionism, in which beauty comes from “within” aka with the assistance of multiple (often very expensive) products we have slathered on to bring forth “natural beauty” and negate the need for heavy, maximalist makeup. In fact, it would be a darn crime to cover up this skin-tending labor with makeup!

“For me, makeup reminds me of work,” Kelly Rowland told People when she posed makeup-free for the magazine’s Most Beautiful issue in 2013. “Without it, I feel natural and untouched.” In light of this, the allure of the unmade (or perhaps more honestly, “undermade”) face is clear. It is very subtle PR, in which the star is at work while appearing not to be. It is a shorthand that suggests authenticity, innocence, higher virtue (because, after all, don’t we as women have bigger things to think of in 2018 than an overly complicated day-and-night beauty routine?), paired with a DIY-style “you could do this too!” and the purest version of Bey’s confidence-bolstering lyric from “***Flawless,” I woke up like this.

Effortlessness as the most coveted virtue is nothing new when it comes to women’s bodies. And magazine covers are the perfect vehicle to disseminate the new rules. Just ask Demi Moore.

Nobody got pregnant before 1991.

They had babies, and they raised those babies, but in the late summer of 1991, actor Demi Moore, photographed by Annie Leibovitz, appeared on the cover of Vanity Fair naked and heavily pregnant. And there has rarely been a year since where the pose has not been replicated in homage. If pregnancy is one of the most natural states a woman can be in, Demi’s artfully naked bump was perfect: beatific and “effortless” (light makeup, adorned with meteor-sized diamonds — what a perfect parallel). That photograph is now in itself a specific cultural language; and for good or ill it “taught” us a new way of seeing and consuming women’s bodies, specifically when they are obviously fecund.

The power of the magazine cover in propagating the ways women should be is still vast. Social media has reach, but everything is on the internet now anyway. Women still look to magazines (whatever form that may take) for their cues; the internet is an accelerant. Fed the uncut Leibovitz photograph via magazine cover, women across the world recreated approximations of it, looking to present their own version of perfect effortlessness. The undermade makeup trend, sanctioned by the power of the magazine cover, is following a similar path into real women’s lifestyles.

The latest dialect in the language of makeup is “understated.” It comes with subtext about freeing oneself from the tyranny of makeup, and places a very specific value on being barefaced and glowing from within. It suggests a democracy similar-but-opposite to that of its more heavy-handed fraternal twin — this is just as accessible as the other option, it says, so why not do it this way? It’s a lie, of course, and one that we consume as we always readily have. All of it is work. Because of course it is. At least with the maximalist trend, a person might get to the yearned-for destination of glamour on the strength of their skill. This undermade trend requires flaw-free genes to begin with, and that’s before we consider the surgical enhancements and other less extreme procedures women are undergoing in this particular beauty moment (microblading, eyelash extensions and tinting, fillers, etc.). According to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, last year soft tissue fillers and Botox were up by 3% and 2% respectively on 2016; there were 15.7 million “cosmetic minimally invasive procedures” recorded in 2017, including some 740,000 microdermabrasions. How fair is that?

Much like Demi making a splash and semi-codifying aspirational pregnancy forever, the no-makeup magazine cover is here to sell appearing as makeup-free as something radical. The barefaced beauties in these magazines are not like the majority of us. The cover’s job is to remind you of that, even as it tells you this is something to aspire to. It’s not a bellwether for a worldwide movement; it’s a display of gentle superiority. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. It’s just the culture right now.

What are Ariana and Gisele and Xtina and Kerry saying with these stripped-back images? Nothing that new, it turns out. It is the shortest route to that much-vaunted quality of relatability. It is a way of displaying bravery, openness, and honesty, a fake reclamation of norms forced upon us in various forms for millennia.

But magazines (and life in general in this capitalist hell!) are commercial enterprises, and these undermade visages are still in the business of selling us millions of dollars’ worth of beauty products, even if it’s made of lactic acid serums, the privilege of a dermatologist on speed dial, and the lottery of favorable genes rather than full-coverage foundation, a highlighting bronzer brick, and a YouTube tutorial. The lofty pursuit of self-acceptance cannot begin or end with whatever the magazines and lifestyle platforms are selling you, whether a revolution in the form of an unmade or maximalist look. Beauty is a business, and in 2018, business is good. ●