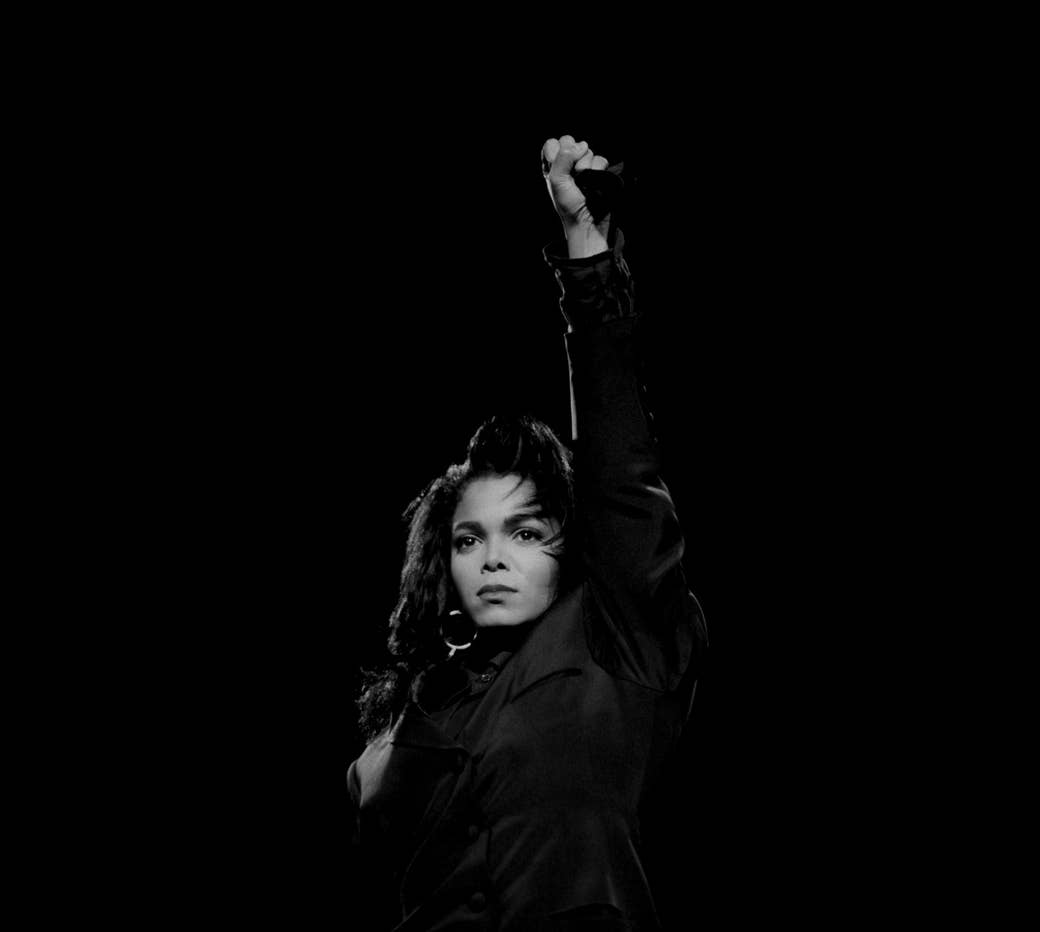

When we think of the big, epoch-shifting pop stars of the ’80s and ’90s, Janet Jackson has been somewhat overlooked by scholars of pop music with short memories. Part of that is the amorphous but ultimately very dull phenomenon of racism. Janet Jackson’s fierce privacy and tight handle over her personal life and what the public can access is another reason. Perhaps she had seen the cost of weakness in whatever form: Her family’s many members were, at the very least, tabloid fodder for decades, whether or not they were actively courting the attention. In 2017, Janet Jackson has lived through the death of her much-loved older brother Michael (the only sibling more famous than she is), through marriage, through motherhood (to 9-month-old Eissa), and most high-profile of all, through divorce. Her world tour, previously derailed by her unexpected pregnancy announcement, resumed last month, with Jackson still in social justice mode: It is now called the State of the World tour (a revision to the Unbreakable World Tour, and also the name of the fourth track from Janet Jackson's Rhythm Nation 1814). She opened her show with a video installation denouncing white supremacy and America’s domestic terrorism.

For those of us who were around for The Velvet Rope, released 20 years ago on October 7, 1997, such actions were a return to form, rather than a sudden segue into fashionable, modern-day activism. Long before the world looked and felt as overtly dangerous as it does today, Janet Jackson never shied away from political opinion. In merging her personal with the political, Jackson’s The Velvet Rope feels, in this current moment, just as pertinent as it did when it was released. The album is a political act, wrapped in the soft glove of pop music, and sitting snugly in the pews of the broad church that makes up black feminist thought.

The Velvet Rope was Jackson’s sixth studio album, and served to continue a journey that had begun with the “awakening” that led to her breaking with her father’s management and direction, ultimately resulting in her third — and breakout — album, 1986’s Control, an ode to independence and strength. At 19, she sang convincingly that control means you get to call your own shots. The softly packaged feminism of the record gave way to the overt sonic and visual theme of social realism on her seminal 1989 album, Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation 1814, for which she made history by becoming the first ever female artist to be nominated for Producer of the Year at the Grammys. On Janet., released in 1993, the open exploration of sensuality and sexuality was revolutionary in a way that seemed to belie her hitherto fierce privacy, but it was a masterful blending of the personal with the political, on her own terms, and inviting listeners to join her there. It wasn’t necessarily original — Nina Simone raged at her piano, and Betty Davis stomped her boots as she funked, for example — but as a modern and palatable pop princess, no one did it better than Janet Jackson.

Crucially, she also set an industry template for later pop stars to bare their souls as mature, evolved artists. In the face of out-of-control press attention and intrusion, Jackson had never appeared to be the obvious power player that she clearly was, when it came to negotiations over her own life. But her records and tours (and how much she chooses to reveal of herself in them) give lie to that notion of powerlessness. She never shied away from politics, and it has been interwoven into her music and legacy. Sometimes this has appeared to be without her explicit consent, as in the aftermath of her infamous Super Bowl performance, but more often than not, she has chosen how she frames her politics, on her own terms. She bucks at being “used” in ways that do not serve her own ends, going as far as to “disappear” rather than participate in moves that would dilute her own beliefs. In an age where the urge is to explicitly make the interior exterior, where celebs need to feel accessible to the plebs, Janet Jackson moves like a real G: in silence.

The Velvet Rope is the venue for the Platonic Ideal of Janet Jackson’s iconic laugh, which sounds like every cliche it’s been afforded over the years: It is sweet and tinkling, sexy and knowing; it feels like uncomplicated joy. In a pause towards the end of “Got ’Til It’s Gone,” it mingles with a chuckle from guest rapper Q-Tip, who’s just asked, “Yo, do you feel that?” The effect is intimate, like you could reach out and touch it and it would touch you back. In the accompanying Grammy-winning promo, created by director Mark Romanek, Jackson is sitting with her chin on her hand, hair collected in Basquiat-esque bunches, white teeth gleaming. The second time she laughs, the visual is of a small black boy being raised aloft by a sea of brown hands. It feels like casual Black Excellence™.

The album concerned as it was with civil justice as it intersects with, for example, the lives of LGBT people and other marginalized groups, resonates still — from the trans military ban to crises around universal health care that will hit women, ethnic minorities, and people living in poverty the hardest. That these messages are wrapped up in catchy pop tracks, tucked between breathy moans and playfully explicit lyrics (sample from “Interlude – Speaker Phone”: “Your coochie gon’ swell up and fall apart”) is irrelevant. In showcasing vulnerability, The Velvet Rope has legs that stretch all the way from 1997 to 2017 — and probably beyond. What she was singing about hasn’t gone away, and in fact, in many cases, it has only been calcified into hardline stances, and then ratified into policy. It was a political album then, and it still is now.

Long before the world looked and felt as overtly dangerous as it does today, Janet Jackson never shied away from political opinion.

Its scope was wide: Janet Jackson had a vision, and she was working with her usual collaborators, producers Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, to achieve it. On the opening line of the first track, an interlude called “Twisted Elegance,” she sets it up. It’s my belief that we all have the need to feel special, she intones, almost whisper-soft. “And it’s this need that can bring out the best in us and yet the worst in us. This need created The Velvet Rope.” The breadth of her range took in domestic violence (“What About”), homophobia (“Free Xone” and a cover of Rod Stewart’s “Tonight’s the Night” with female pronouns left intact), both ancient and modern sexual lifestyles (BDSM on “Rope Burn” and online relationships on “Empty”), masturbation (“Interlude – Speaker Phone”), AIDS and the grief of losing loved ones to it (the champagne bubbles–light “Together Again”), depression (“Interlude – Sad”), love (everything else), and so much more. Remember, in October 1997, Will & Grace was still a full year away from airing its pilot episode and gently nudging the American public further towards the idea that gay people might be human. Just a couple of years before, a jury had found O.J. Simpson not guilty of murdering his ex-wife Nicole Brown. A star of Jackson’s caliber, magnitude, and reach tackling subjects like these — via a mix of funk, pop, R&B, trip-hop, and spoken word interludes that, 20 years later, still feels like something all its own — was A Big Deal.

The public seemed to agree. Sales-wise, TVR sold far fewer than Janet. had just four years earlier, but even so, it went three times platinum in the US and reached the No. 1 spot on the Billboard 200. Her audience spoke the loudest on her single “Together Again,” which remains the biggest selling single of her career — and one of the biggest-selling in history. At the time of its release, the album received fair to good reviews: Entertainment Weekly praised its honesty above all, with reviewer J.D. Considine comparing it favorably with Joni Mitchell’s Blue. Rolling Stone’s Ernest Hardy identified its place as a political piece of art in the continuum of Jackson’s output, but lamented its latter half, describing it as merely “brush[ing] up against brilliance.” SPIN named it one of the albums of the year.

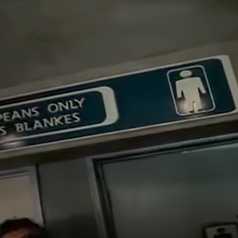

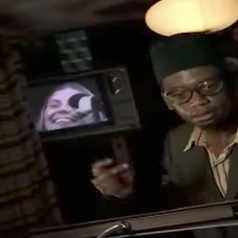

The sound of TVR was not the whole meal — the look of it was meticulous too. The “Got ’Til It’s Gone” video is perhaps the most enduring visual of the record, and that’s no accident. Director Mark Romanek’s vision for the video was inspired by African photography he’d seen in Drum, a South African magazine, and evoked work that was already iconic. The styles of photographers Malick Sidibe and James Barnor, Malian and Ghanaian respectively, in which they captured glamour in the everyday dignity of black folks, were heavy influences. All the hallmarks of their work — studio settings, transistor radios and old TV sets, boxing gloves, motorcycles, and of course, formal postures and expressions that contradict the party setting — were present.

The video served to introduce these artists to a mainstream (read: mostly white, American) audience, while impressively managing to appear largely unburdened by the inevitable white gaze it would attract. It was unapologetically black, and you didn’t need the final image — a beer bottle smashing against an Afrikaans/English sign reading SLEGS BLANKES/EUROPEANS ONLY — to tell you that.

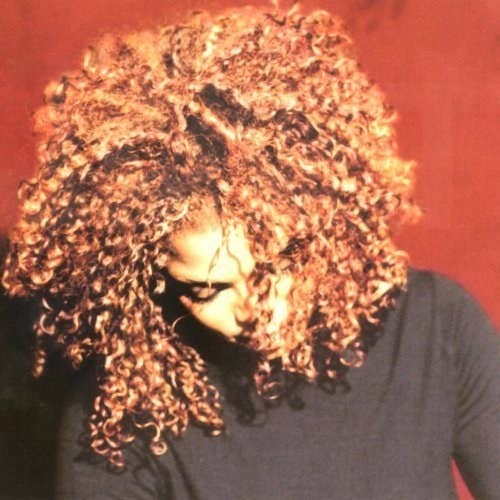

But then the visual language of The Velvet Rope was striking all round. The alternate cover of the Janet. album (in which the singer’s breasts are covered by the hands of her ex, producer Rene Elizondo Jr.) is perhaps the most iconic version of ’90s Janet, but the art of The Velvet Rope follows closely behind. Taken by photographer Ellen von Unwerth, the cover is another artist portrait, this time with her face partially obscured, and rocking vibrant red curls. It could be read as a vulnerable image, representative of some of the record’s themes, but in the album promo — also photographed by von Unwerth — the vision expands. She shows up in red and blue-black vinyl with a ring over her right nipple; she turns her back on the camera, revealing a lower back tattoo; she appears in a robe, smiling at the camera; she “smokes” a fat faux-cigar; and in a couple of shots, she notably reclines on a chaise, bound at the wrists by the titular rope, and later with it between her teeth. The result is a sort of hands-off eroticism; Janet had done “sexy” before, but for the private star, this felt like a concerted stripping down of layers, before even hearing a single note.

The kernel at the album’s core was pain, though, rather than a studied performance of black excellence or coquettish sex kitten, and a lot of it was drawn from Janet’s own wellspring. In an interview she gave to MTV around the time of the release, she detailed the process of exploration that led to the songs on the record. “It's childhood, it's my teenage years, my adulthood,” she told John Norris. “Lots of things that I have just carried with myself, around with me. And I had my escapism so that I wouldn't feel that pain. Ways of dealing... I think we all do that.” In another interview, with Newsweek in November 1997, the singer said it even more plainly: “I was very, very sad. Very down. Couldn't get up sometimes. There were times when I felt very hopeless and helpless, and I felt like walls were kind of closing in on me.”

The knives were certainly out after the Super Bowl halftime show “wardrobe malfunction” of 2004, for which she was more or less thrown to the wolves; she had learned the hard way what comes when your exposure is not by your own design. Even so, Janet Jackson never withdrew, even when she was facing personal and public demons. But she never embarked upon an apologetic “reconciliation tour” on the reality series circuit, for example. There was no self-flagellation for the public — of the brouhaha around “Nipplegate” she said “...there are much worse things in the world, and for this to be such a focus, I don't understand” — and she has never participated in arenas where she did not wish to be. She never needed it.

The lack of apology for the way Janet Jackson has chosen to live her life — up to and including her marriages, first-time motherhood at 50, and divorce(s) — and her choice to journey inwards before looking out make The Velvet Rope sound as raw as the circumstances that birthed it. In interviews around the time of the album’s release, Jackson had spoken about the body dysmorphia that plagued her younger years, leading to eating disorders and depression. This was vulnerability she was willing to expose in the form of her art. Rope was a delivery mechanism that was accepted and understood not as a lecture, but as a valuable insight — the softest of revolutions, but one nonetheless.

Think of it as as sort of like Beyoncé’s Lemonade before Lemonade: the personal story of one black woman, extrapolated and taking on new cultural and political significance in the process. On TVR’s final, hidden track, “Can’t Be Stopped,” Jackson sings to a weary audience of black people, “The pressure seems to, to defeat you / Beat you, whenever you can't go on,” which feels like a forebear to Solange’s “Borderline (An Ode to Self Care)” from 2016’s A Seat at the Table. On “Interlude – Sad,” Jackson talks of watering a “spiritual garden” (“There's nothing more depressing than having everything and feeling sad”). There is something to be said for being in the vanguard of such a movement, and Jackson occupies that space, while leaving room for herself and her art to still evolve. Without her — and arguably without The Velvet Rope — there might have been no room for Lemonade. It’s worth noting, and celebrating.

Last month, Jackson donated proceeds from her Houston show to local flood relief charities after spending time with victims of Hurricane Harvey. The tradition of marrying intention and direct action to her art is the Janet Jackson way, and The Velvet Rope was in many ways her last big “social justice” record in that respect. Even when she goes away (most recently while married to Qatari businessman Wissam Al Mana), she’s around, relevant to the zeitgeist, by virtue of her art and life. In a climate where pop singers (and athletes, and TV hosts and journalists, among others) are being told to shut up and stop talking about politics, Janet gets to dust off old habits. She’s not new to this. And the 20th anniversary of her quietest, most beautiful album is a good time to remember that. ●