Over the past six weeks, coronavirus testing in the United States has been dogged by both bureaucratic bungling and technical errors, leaving public health authorities largely ignorant of the true extent of the outbreak. While US confirmed cases just crossed the 5,000 mark, some experts estimate the real count is closer to 50,000, with most undetected as states scramble to get wide-scale testing underway.

The government’s failures affected every step of the testing process, from the initial throat swab to the genetic sequencing. Here’s how.

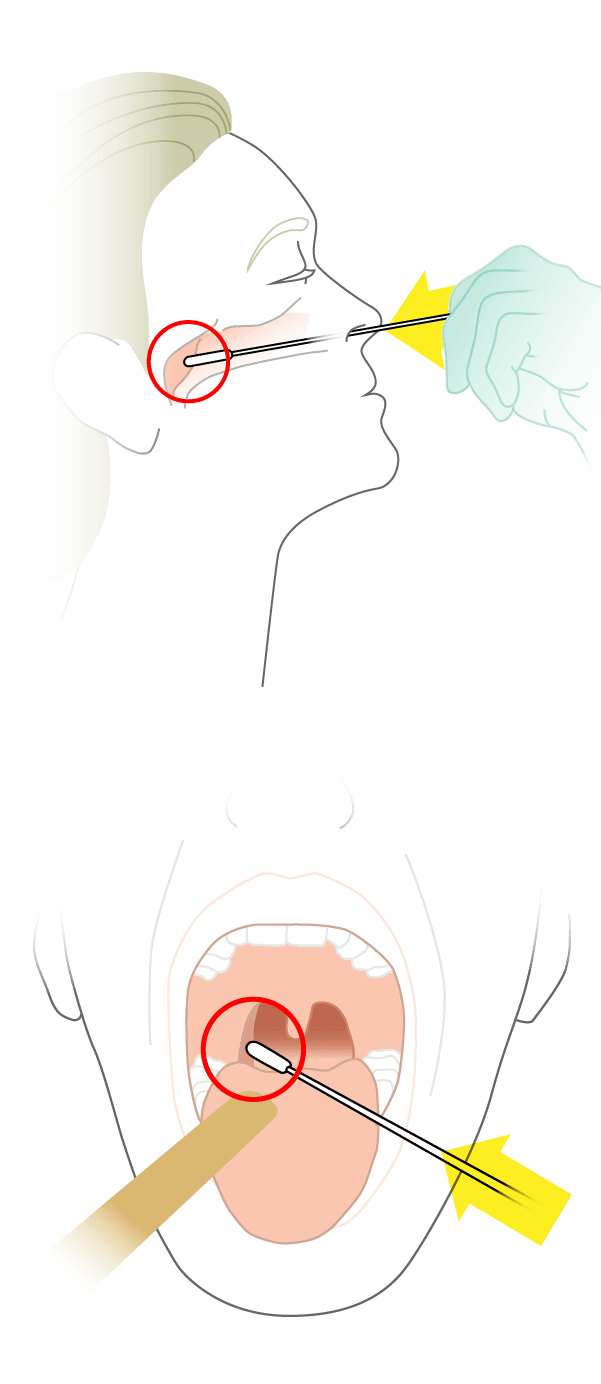

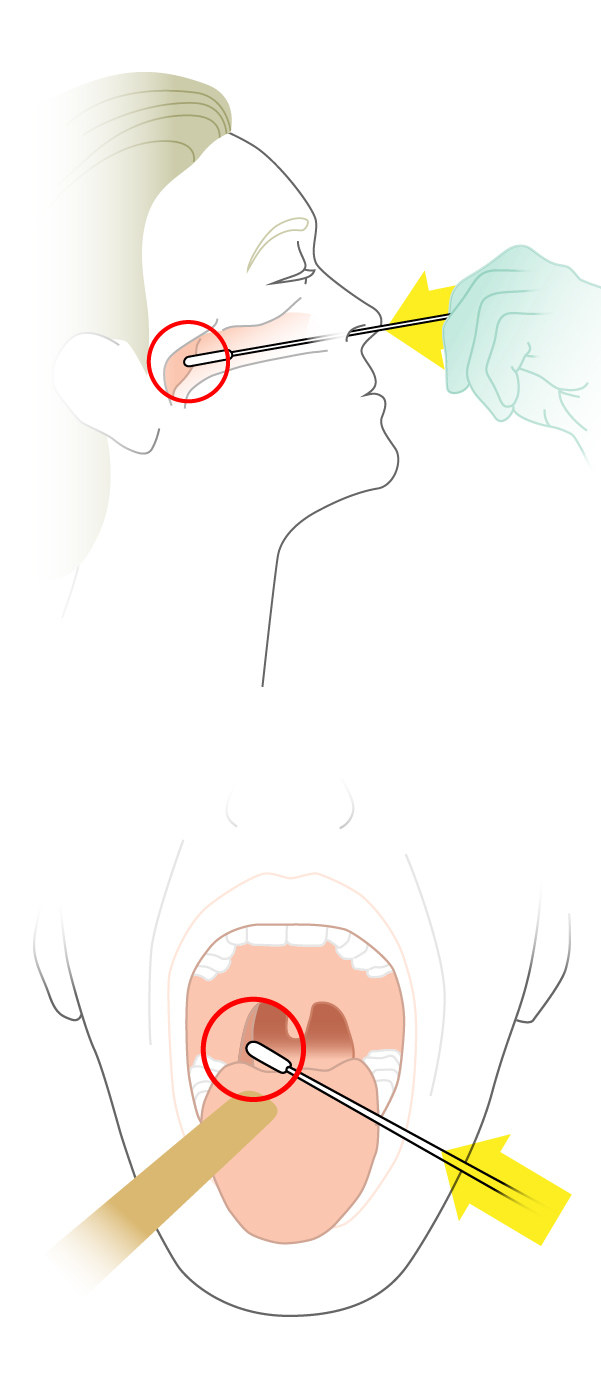

Step 1: Collect Samples

Patient is swabbed in the nose and throat.

What Went Wrong

Until the end of February, the CDC guidelines only allowed testing of people who had traveled to China or who had had contact with those travelers, missing lots of people who had worrying symptoms but did not know of any such contacts.

Even now, state and local health departments have a confusing patchwork of requirements for testing.

In early February, the FDA had only approved the CDC’s test, barring the use of similar tests from other laboratories and the very effective test from the World Health Organization.

Unlike South Korea, which planned for drive-thru swab collection to accelerate testing, the US has largely relied on in-office swabbing, wasting time and equipment.

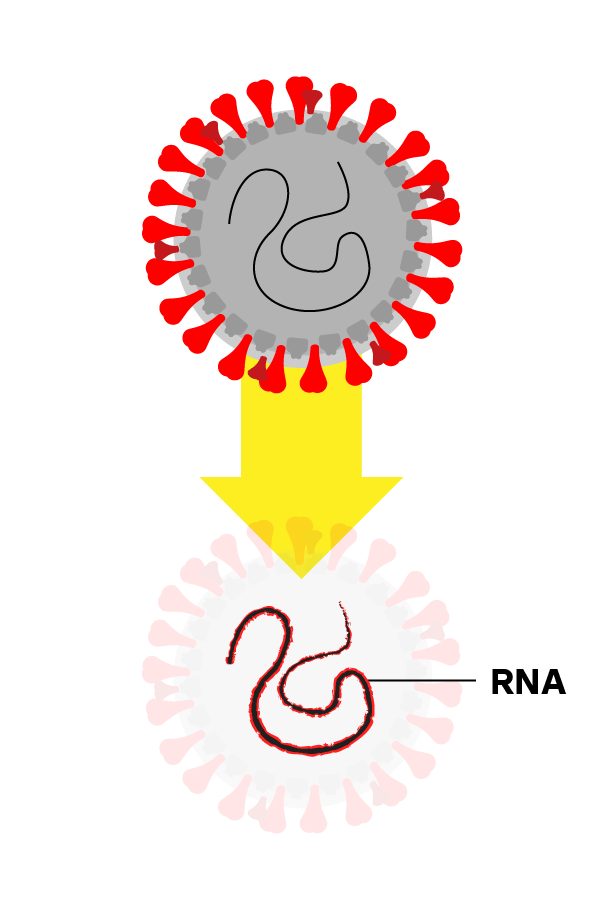

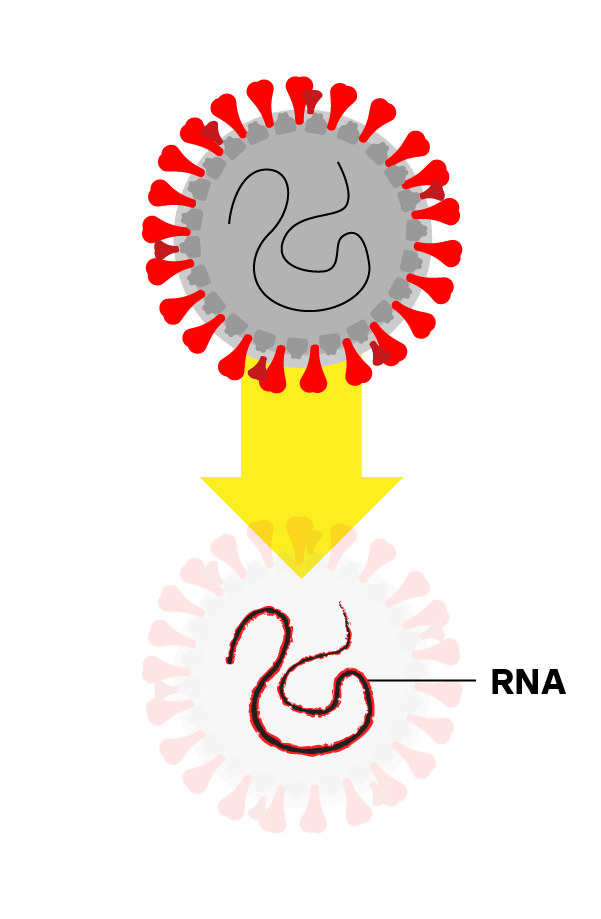

Step 2: Isolate the Virus’s RNA

Chemicals break apart the virus and stabilize its genetic material, called RNA.

What Went Wrong

The CDC test required proprietary kits for isolating the virus’s RNA from swab and spit samples. These kits promptly ran out, slowing testing.

South Korea invested in equipment and staff to automate these tests in large batches. The CDC test, in contrast, is slow and labor-intensive.

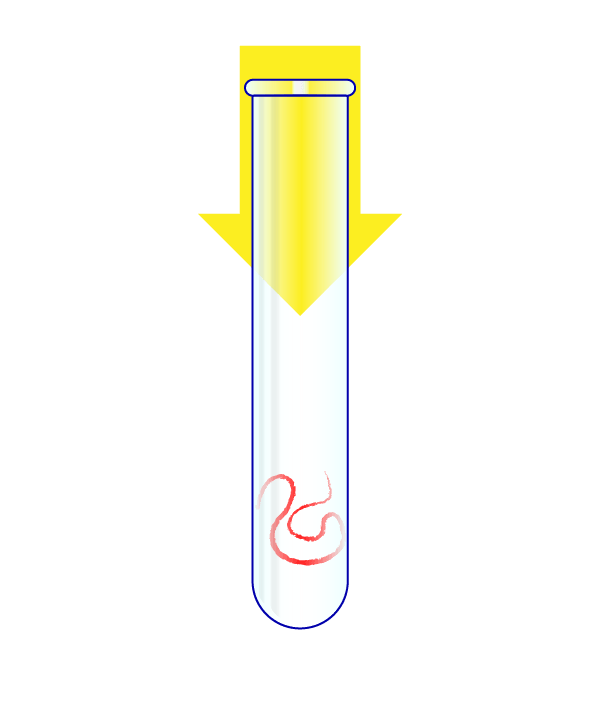

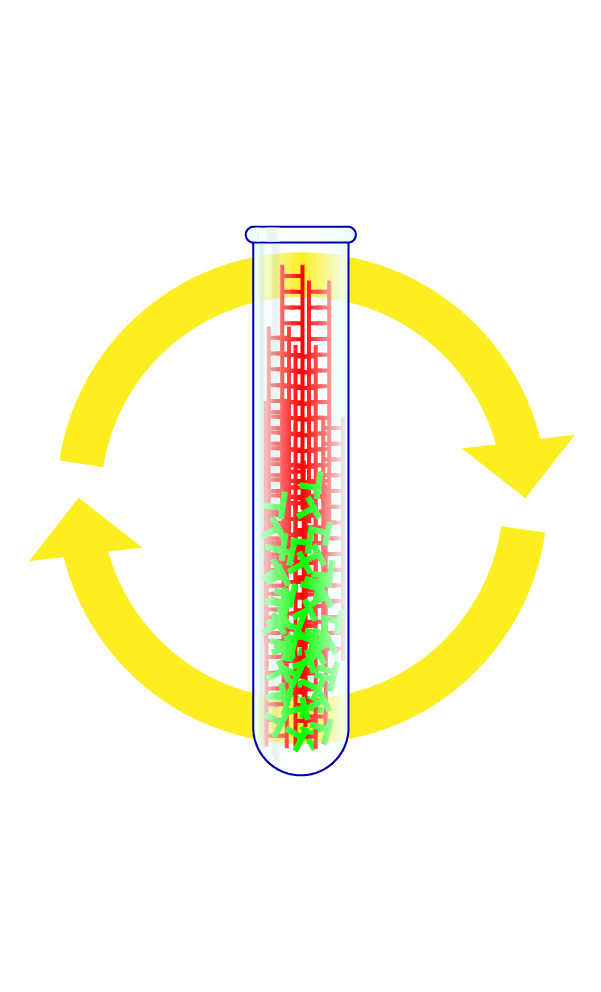

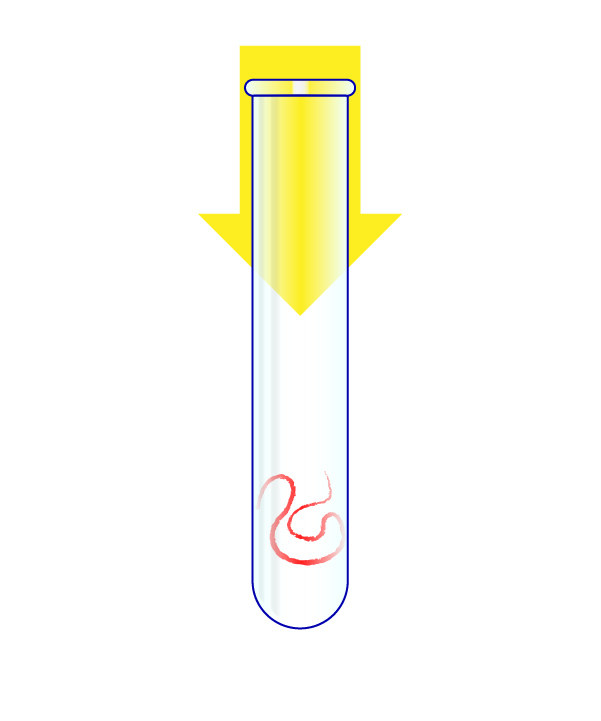

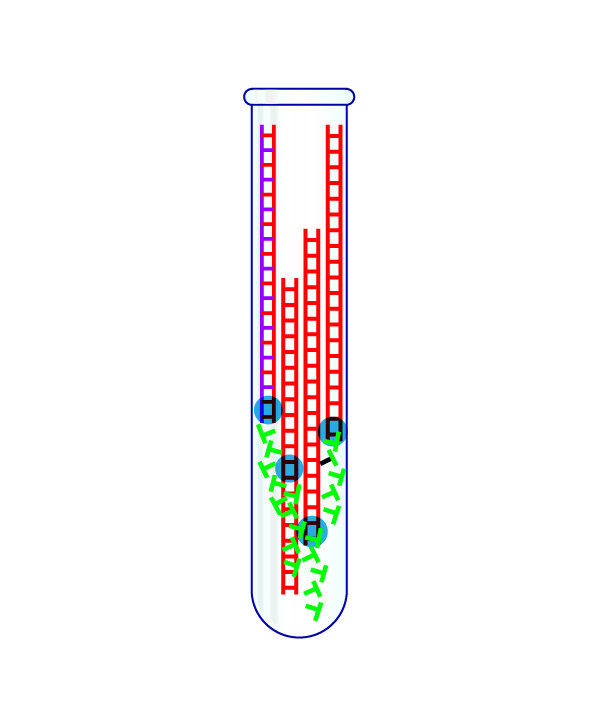

Step 3: Turn the Virus’s RNA Into DNA

The virus’s RNA is put in a test tube.

The RNA is transformed into DNA, and that genetic material is heated to split it in half. A “primer” that is specific to the virus then attaches to the DNA, and another chemical then doubles the amount of this genetic material. With each doubling, a fluorescent signal is fired by the chemical reaction.

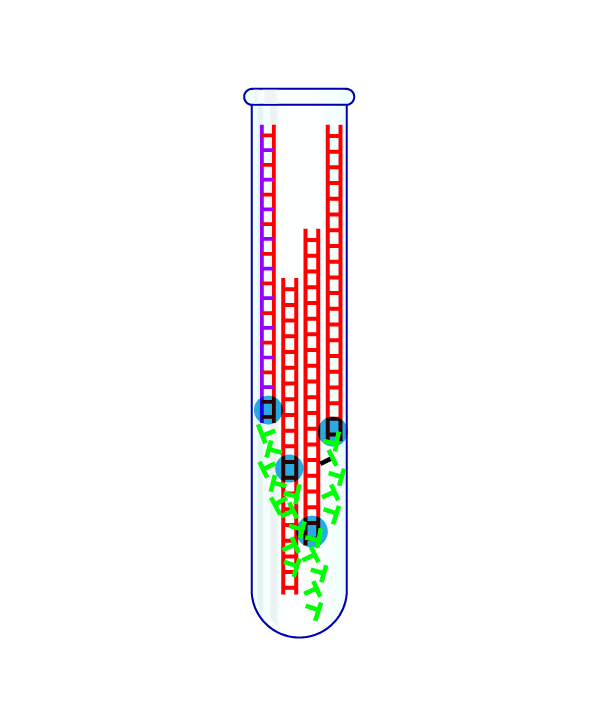

What Went Wrong

The CDC supplied three of these primers with each test. One primer proved unreliable for nearly every lab that tried it, as did a second one in some big public health labs, notably New York’s.

Despite these failures, the CDC and FDA did not give other labs permission to make their own tests until the end of February, losing a month of testing time.

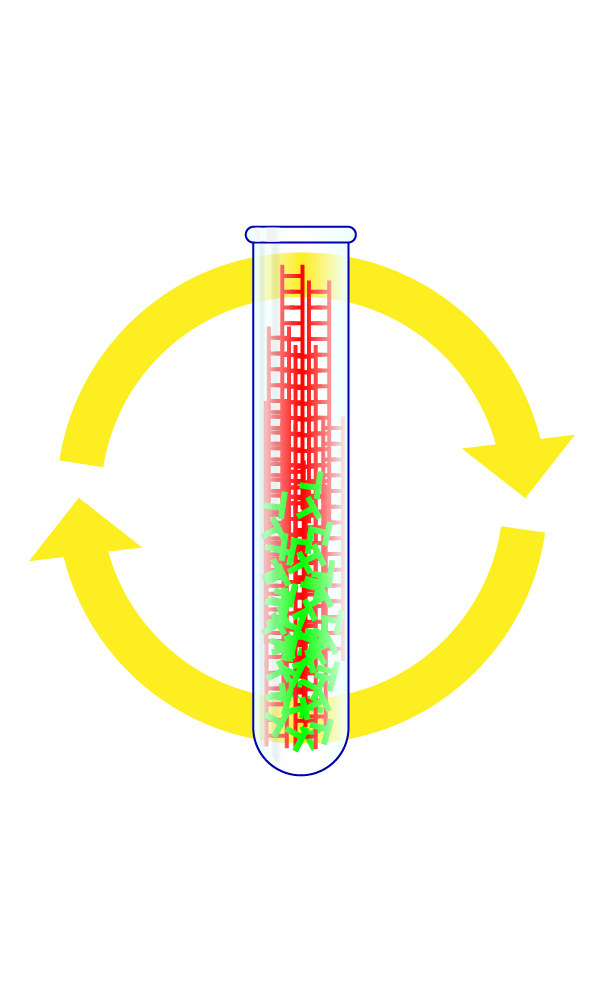

Step 4: Repeat the Cycle Dozens of Times

By watching whether the fluorescent signal grows with each cycle, scientists can tell if a patient's sample had the virus in it. When done correctly, each test should take only about a few hours to complete.

What Went Wrong

In the US, results are often taking four or more days if they are available at all.

Federal officials waited until early March to invite large private labs, which can run thousands of tests a day, to begin coronavirus testing, leaving the US with a backlog of swab samples even as case numbers double every two days.