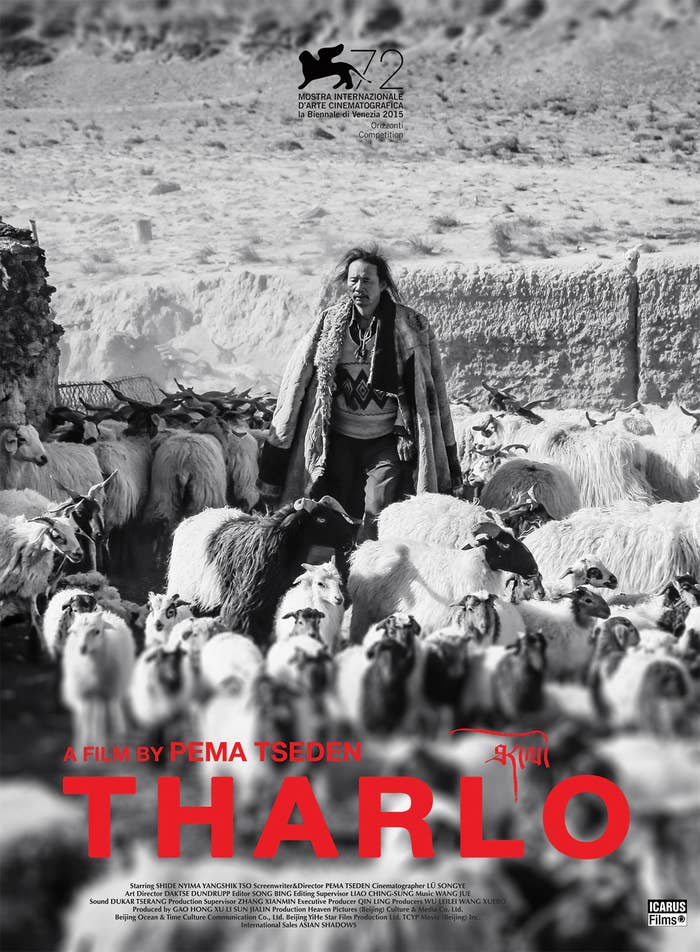

NEW YORK — There are probably thousands of people like Tharlo in the Tibetan Plateau. Middle aged, hair tied up in a ponytail, they seldom talk with others, spending days and nights herding sheep in the mountains, never setting foot in the outside world. There's nothing extraordinary about them, save their lingering ability to recite a string of quotations from Mao Zedong back-to-back, rapid-fire in Mandarin, revealing traces leftover from the dark days of the Cultural Revolution.

Acclaimed Tibetan director Pema Tseden’s feature film Tharlo, an adaptation from the director and writer’s own novella, follows the gripping journey of one such shepherd after being ordered to acquire a government-issued ID. The film debuted at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York on Wednesday and is scheduled to run through November in various of cities across the US.

With limited foreign access to Tibet and a Chinese film scene that is almost impossible to separate from politics, Tseden said he is here to provide something that’s been long-missing: an insider’s look at Tibet from a Tibetan.

“[Foreign-made films about Tibet] sometimes pay excessive attention to ideology,” said Tseden in an interview with BuzzFeed News in New York last week, where promised to stay objective. “And mainland [China] does the same, just with a rather different ideology.”

What the poetic black-and-white film does is something in-between, walking a particularly fine line to grasp the lives of ordinary Tibetans who struggle between adhering to traditions and moving on to the modern reality of Tibet. It doesn’t blatantly try to manipulate viewers on Tibetan issues, and avoids the misrepresentation that Chinese films created on Tibet by the majority Han ethnic group almost always come burdened with.

“The previous Tibetan-themed films [made by China] used Han Chinese actors and delivered lines in Mandarin. Basically, those were Han Chinese stories told wearing Tibetan clothing with numerous false details,” said Tseden. “I want to change that environment, by making films of our own.”

Tseden, who currently lives in Beijing, is the son of nomadic herders. He was born and raised bilingually in both Tibetan and Mandarin alongside two younger siblings in a Tibetan majority county in Qinghai Province, traditionally referred to as the Amdo Tibet. Tibet's status in China remains a touchy subject: the Chinese government maintains that the current Tibet Autonomous Region and autonomous prefectures to the east governed by Beijing have been part of China "since ancient time;” Tibet says that the Han control became void after Qing Dynasty fell in 1912 and it spent years operating as a de facto independent autonomy before being incorporated into the People Republic of China in 1951. (The event is known in China as the "peaceful liberation of Tibet." That narrative was repudiated by the 14th Dalai Lama after he was exiled to India, claiming the consensus was reached by "the threats of arms.")

As China’s first director to make films entirely in the Tibetan language, the director, 47, has won numerous awards abroad and at home with Tharlo and previous works such as Old Dog and Soul Searching. His career has been one of rapid ascension: he was the first Tibetan director to graduate from China’s prestigious Beijing Film Academy in the early 2000s, and sat on the jury this year for the Shanghai International Film Festival. Tharlo is also set to release widely in China, a reception none of his previous works enjoyed.

He selects his words carefully when it comes to Beijing’s rule over Tibet or anything else political. Still, the way he probes the concept of Tibetan identity gives new life to the cliched cultural touchstones that resonate with Tibetans.

For a long time, the only films available to moviegoers in Tibet were socialist propaganda films. One of the most striking examples was Nongnu, or Serf, a 1963 film made by a state-run film company showing the brutal suffering of Tibetans under the rule of corrupt monks and rich landowners in a feudal society. Today, Tibetans understand it was Chinese propaganda, but back then, with nothing else available, young Tseden watched it over and over again in horror. “It probably made Tibetans feel inferior, and casted doubts on the culture we lived in,” said Tseden.

As China’s economy has become more market-driven, “Tibet fever” has attracted hundreds of thousands of Chinese tourists to spend days on a scenic train ride to the Tibetan Buddhist holy land for the purpose of “spiritual purification,” a trip that’s especially popular among the country’s hipster crowd. While the Chinese generally hold a hostile attitude towards the Dalai Lama as a “separatist” after years of Communist Party’s successful propaganda campaigns, the rest of the world disagrees. That difference of opinion has caused Western celebrities to be banned from promoting their works in China if they’re viewed as standing with the Tibetan government-in-exile. (Brad Pitt was banned from entering China for over a decade for his appearance in Seven Years in Tibet, a film that suggested that Beijing invaded Tibet.)

Tseden was surprised when he learned that script of Tharlo, a film that touches upon the Cultural Revolution and its aftermath, passed the government’s censorship check. Chinese directors have almost all complained about strict censorship, but according to Tseden, it’s been especially bad for Tibetan filmmakers: while the censorship board requires a short synopsis for Han Chinese films, Tibetan films have to have a full script ready for review; the Administration of Radio, Film and Television is the only censor for Han films, but the United Front Work Department, a government agency that manages minority issues, has to be involved for Tibetan films; and there’s nothing close to a timeline for approval.“You’ve just got to wait,” said Tseden. The topics cleared are extremely limited and regulated. “Special political incidents” such as crackdown on Tiananmen Square, are of course a no-go, and stories involving too much content on Tibetan history or religion are doomed as well.

“Censorship disrupts the consistency of creative works,” said Tseden, who deemed writing a tool with much more freedom. “My recent films are kind of spontaneous. There is a frame indeed, but I get to tell what I want to tell.”

In Tharlo, Tseden uses all the tricks available to him to press his point without being heavy-handed. In the opening scene, a well-placed chimney pipe separates Tharlo and the police chief, a symbol of the divide between the state and Tibetans; he relies heavily on reflections in mirrors to play with the line between reality and illusion; Tharlo questions a police chief on the meaning of a passage in a Mao speech, pushing back on an unthinking authority figure.

The film taps into a growing sentiment among some Tibetans who worry the lost of their identity and heritage reached a peak last month when a Tibetan advocate for truly bilingual education was detained by police after speaking to the New York Times. In Xining, the capital city of Qinghai Province where over 120,000 Tibetans reside, people have been asking for the first Tibetan-language elementary school to be set up.

In Tibetan, Tharlo means “escaper.” It’s fitting, as the film is about a loss of identity, which is a fear Tseden acknowledged sharing. That’s why he decided to make his films completely in the Tibetan language, and two years ago, he sent his city-born son back to a Tibetan temple for a Tibetan-language bootcamp. Tseden was pleased with the outcome: his then high-schooler son brushed up on the language and quite a bit of the cultural context, he said.

Faraway from his hometown, in the Han Chinese capital pursuing his career, Tharlo could be a stand-in for Tseden himself. “It’s all about losing and searching. With few Tibetan signifiers in Tharlo, many people feel related with Tharlo. Their feedback is that it’s not a Tibetan story, it’s a story of many, a story about identity.”